https://asiatimes.com/2021/11/chinese-exports-support-global-supply-chains/

US and EU economies hang on Chinese imports

Dampening inflation, China is a silent partner of the Fed's Open Market Committee and the European Central Bank

US and EU economies hang on Chinese imports

Dampening inflation, China is a silent partner of the Fed's Open Market Committee and the European Central Bank

by David P. Goldman November 8, 2021

The flexibility of China's exports is helping to keep inflation down in the US and the EU.

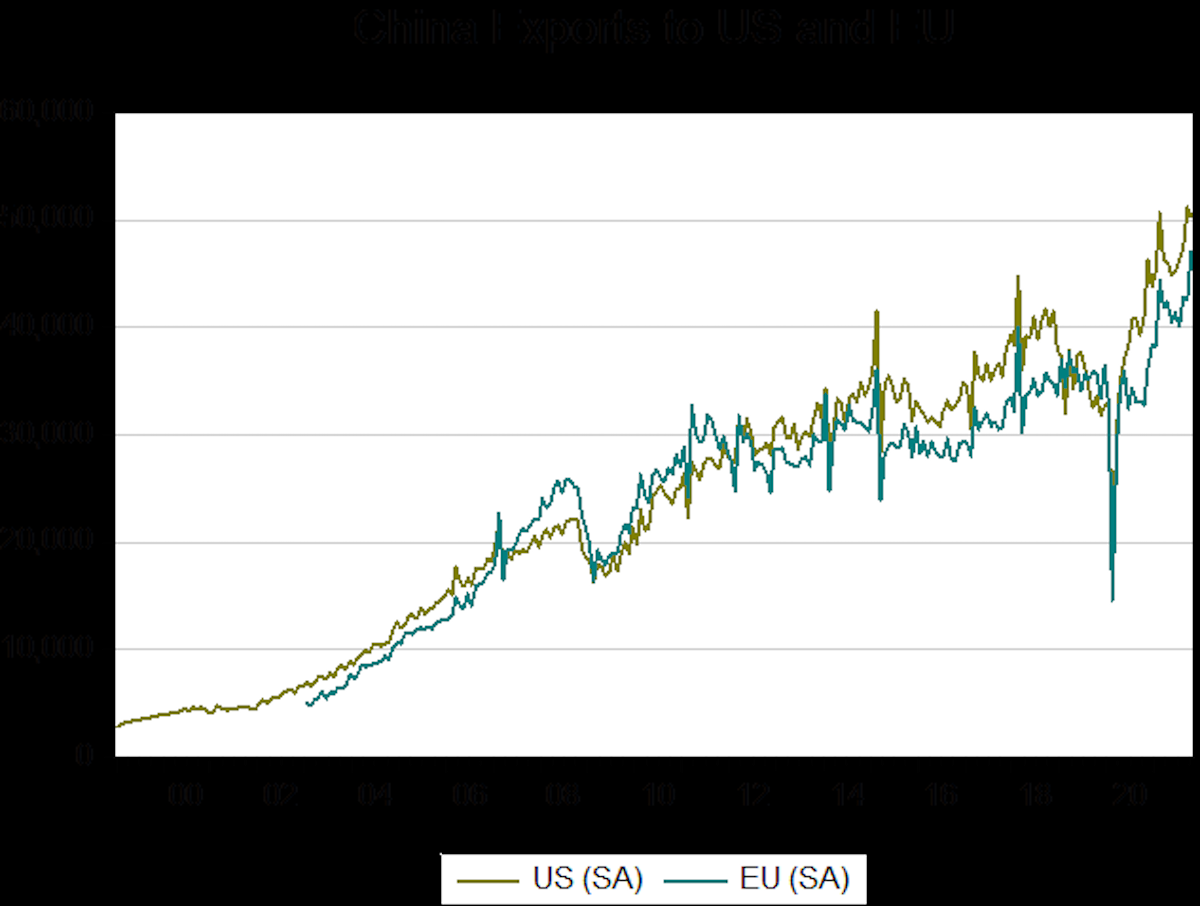

China’s exports to the United States and the European Union now amount to nearly 30% of manufacturing GDP, after an unprecedented surge in shipments this year. US imports from China are 30% higher than before the Covid-19 pandemic, and Europe’s imports are 50% higher. These margins of increase have an important macroeconomic impact.

The chart below shows seasonally-adjusted Chinese exports to the US and European Union.

China’s exports to the United States and the European Union now amount to nearly 30% of manufacturing GDP, after an unprecedented surge in shipments this year. US imports from China are 30% higher than before the Covid-19 pandemic, and Europe’s imports are 50% higher. These margins of increase have an important macroeconomic impact.

The chart below shows seasonally-adjusted Chinese exports to the US and European Union.

China’s exports to Taiwan and South Korea have risen even faster.

Taiwan and South Korea, in turn, are important suppliers of industrial goods – especially electronics – to the West, and their imports from China include components that are re-exported to the US and Europe. This reflects closer economic integration among the major Asian industrial economies.

In effect, China’s export sector has become an economy within the economies of the US and Europe, meeting a margin of demand for manufactured goods equal to nearly 30% of the industrial nations’ manufacturing GDP.

China’s ability to increase exports gives the industrial nations more room for monetary and fiscal stimulus. In the case of Europe, a 50% increase in imports from China during the past two years amounts to about 2% of overall GDP, and about 14% of manufacturing GDP. China’s flexibility in increasing supply allows Europe to increase demand.

In the US, higher imports from China amount to a $250 billion increase in supply at a time when demand for consumer electronics and other consumer goods jumped along with fiscal and monetary stimulus.

The cost of Chinese goods rose after the pandemic, following years of decline. But the net effect of the surge in Chinese imports is to dampen inflation. The US Consumer Price Index for durable goods rose by 14% between January 2020 and September 2021, while the cost of Chinese imports rose by only 4%. By providing nearly 30% of US goods consumption, China has allowed the US to conduct an unprecedented level of monetary and fiscal stimulus with considerably less inflation than it otherwise would have sustained.

That makes China a silent partner of the Federal Open Market Committee and the European Central Bank. Global supply chains have held up better than they otherwise would have because China’s industrial machine contributed more to supply. The electric power disruptions during the third quarter do not seem to have slowed China’s export growth, and the worst of the problem appears to be over, judging from the sharp fall in local coal prices.

China’s 4.9% GDP growth during the third quarter was the result of deleveraging in the property sector, which reduced the investment contribution to GDP to its lowest level in many years. Investment has been an outsized driver of GDP growth in China, and the slowdown was inevitable.

As China’s government revives housing investment, though, growth should pick up. As I noted in a November 6 report, consumption growth remained on the long-term trend line during the third quarter, while industrial performance—reflected in the strong export data—was extremely strong.

Infrastructure and industrial capacity are the tough problems for any economy to fix, and China appears to remain strong in these areas. Real estate investment is a short-term cyclical problem and relatively easy to fix. The strong export data back up my November 6 forecast that Chinese growth will pick up in 2022.