The Face of China: A Globetrotting Diplomat Armed With U.S. Admonitions

While Xi Jinping hasn’t visited another country in the pandemic, his foreign minister, Wang Yi, has been to dozens, extolling Beijing’s vision for the world.

Wang Yi, China’s foreign minister, at a Group of 20 meeting in Bali, Indonesia, last month. He has been to more than 30 countries this year.Credit...Pool photo by Stefani Reynolds

By Jane Perlez

Aug. 21, 2022

China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, a dapper man in well-pressed suits, keeps up a relentless travel schedule, more than 30 countries so far this year, to places big and small: island nations in the Pacific, Central Asia on China’s western periphery and, often, Africa.

He is the campaigner for the global ambitions of his boss, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, carrying the message that Beijing will not be pushed around, least of all by the United States.

During a meeting last month with Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken in Indonesia, Mr. Wang arrived with a list of four “wrongdoings to be corrected,” including that the United States must rectify its “serious Sinophobia.” Relations would be at a “dead end” if the demands were ignored, Global Times, a nationalist Communist Party newspaper, warned later.

As China carves out its place in a changing world order, Mr. Wang has been its public face, particularly because Mr. Xi hasn’t visited a foreign country since the start of the pandemic. Mr. Wang has been extolling Mr. Xi’s vision for China as a global leader that embraces the developing world and that leads an authoritarian axis against the United States and its allies.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Mr. Wang has largely avoided Europe, where Beijing is seen as friendly to Moscow and China’s approval ratings have plummeted. He has been the standard-bearer for a hardened stance against Taiwan. And he has worked to align Muslim countries with Beijing, in part to ensure a bulwark against Western criticisms of its mass detention of Uyghurs, a Muslim minority.

Mr. Wang, far left, meeting last month with Secretary of State Antony Blinken, second from right, in Bali. Mr. Wang’s only trip to the United States during the Biden presidency was a rancorous meeting last year in Alaska.Credit...Pool photo by Stefani Reynolds

He has visited the United States just once during the Biden presidency: a bitter meeting in Anchorage with Mr. Biden’s two senior diplomats early last year.

Mr. Wang rebuked Mr. Blinken and the president’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, then for imposing sanctions on Chinese officials 24 hours before the meeting. “This is not supposed to be the way one should welcome his guests,” Mr. Wang said at the outset of the talks.

In a not-so-subtle way, Mr. Wang is setting up a fight for Asia, with China in one corner and the United States in the other.

“China’s argument is that Asian problems should be solved by Asians,” said Bilahari Kausikan, former foreign secretary of Singapore, who has been with Mr. Wang in closed-door diplomatic meetings. “The argument also says that the U.S. is an unreliable troublemaker.”

It comes directly from Mr. Xi. “It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia,” Mr. Xi said in 2014 in the early years of his presidency. In this doctrine, the United States is a decades-long interloper in the region and a fading power.

The premise doesn’t always sit well, Mr. Kausikan said. It can be interpreted by Asian diplomats as Mr. Wang’s positioning China, the region’s biggest economy, as a rich bully, calling the shots in a region with other powerhouses, like Japan and South Korea, both American allies.

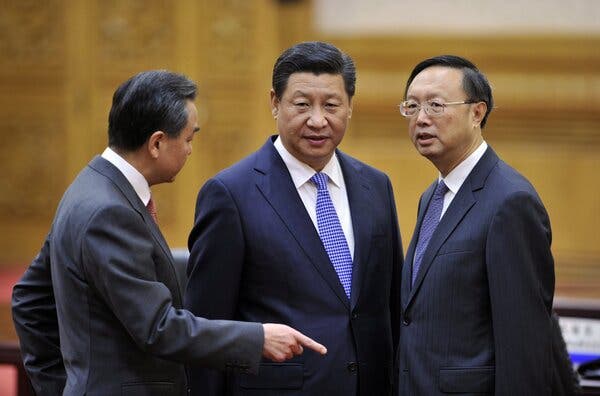

President Xi Jinping of China, center, sets the messaging for Mr. Wang, left. “It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia,” Mr. Xi said in 2014.Credit...Pool photo by Parker Song

In some Asian countries, the approach works, especially when accompanied by flattering phone calls from Mr. Xi, or even an audience with him. Last month, President Joko Widodo of Indonesia was invited to Beijing to meet with Mr. Xi, a trip the Indonesian leader considered an honor. Mr. Joko announced in a recent interview with Bloomberg News that Mr. Xi and President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia will attend the annual summit of the Group of 20 leaders in Bali in November.

Appointed in 2013, Mr. Wang, 68, is one of China’s longest serving foreign ministers in recent memory.

Mr. Wang was China’s ambassador to Japan in the mid-aughts when Beijing was interested in improving relations with its former enemy. He speaks fluent Japanese and in Tokyo he played golf with Japanese businessmen.

He was a “gentleman, not a warrior” in Japan, said Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center, a Washington-based research group. “Then he became foreign minister, and he became entirely different.”

A new acerbity surfaced when Mr. Xi warned Chinese diplomats that they needed a “new fighting spirit” during a period that coincided with mass protests in Hong Kong against the Communist Party’s rule.

Word went out that the foreign ministry was too tame. Mr. Wang lit a fire. To rounds of applause, Mr. Wang repeated the mantra of a “fighting spirit” at a 70th anniversary party of the ministry in 2019.

His brusque demands on behalf of Mr. Xi have earned him a sobriquet among young Asian diplomats: Cao Cao, after a wily Chinese statesman of the second century, Mr. Kausikan said.

Mr. Wang, then the vice foreign minister, at six-party talks in 2004 on dismantling North Korea’s nuclear program.Credit...Pool photo by Goh Chai Hin

The hard-line approach has been fortified by Mr. Xi’s friendship with Mr. Putin.

Mr. Wang was an early doubter of their alignment, according to two diplomats who spoke on the condition of anonymity given the political sensitivities. But he has since morphed into a firm supporter of a China-Russia axis.

At a recent conclave in Cambodia, Mr. Wang made a pointed _expression_ of the new friendship. As the Japanese foreign minister prepared to address the crowd of assembled dignitaries, Mr. Wang conspicuously walked out with his Russian counterpart, Sergey V. Lavrov.

“Both Russia and China are creating a shared discourse that they will not be told what to do by liberal powers about their ‘core interests’ as they define them — Ukraine for Russia, Taiwan for China,” said Rana Mitter, a professor of Chinese history and politics at Oxford University. “Wang Yi would have had to have top-level authorization for such a gesture.”

Early in his rule, Mr. Xi launched an array of foreign gambits to develop geopolitical ties through investment, paying close attention to Africa. Following that example, Mr. Wang traditionally begins each year with visits to several African countries, where the foreign minister has a softer touch.

He showed up in Zambia, a country struggling with significant debt, in March. Two months later, Mr. Xi called the new leader there, Hakainde Hichilema. By July, China had made an unusual concession on its $6 billion loan to Zambia, in openly agreeing to restructure the debt.

A top priority for Mr. Wang is to keep the United States off balance in the Asia-Pacific.

Recently, Mr. Wang put in a punishing 10 days flying around more than half a dozen small countries in a Boeing 737, staying at nice but less than palatial hotels.

Mr. Wang arriving in the Solomon Islands in May. A security deal reached this year allows China to build a port in the Solomons for commercial and possible military use.Credit...Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

He arrived in Fiji in late May, then flew to the Solomon Islands and other countries, expecting to get them to sign a “Common Development Vision.” In the Solomons, where Mr. Wang has had the most success, he signed a separate security deal that allows for China to build a port for commercial and possible military use.

But the countries Mr. Wang visited refused to sign the development document that would have given China the right to projects on cybersecurity and ocean mapping. Some of the countries cited concerns about aggravating the rivalry between the United States and China.

“They think they can walk in and everyone is going to bow down,” said Dorothy Wickham, founder and editor of the Melanesian News Network, who covered Mr. Wang’s visit. “They don’t understand that money is not everything.”

It’s an uncertainty that pervades China’s diplomatic strategy — and by extension Mr. Wang’s mission.

When the United States withdrew from Afghanistan a year ago, China seemed unsure whether it was an opportunity or a headache.

In March, Mr. Wang turned up in the Afghan capital seeking to build rapport with the Taliban. He met almost furtively with Siraj Haqqani, the interior minister. A photograph of Mr. Wang by an Afghan news agency shows him with his back to the camera and his hand stretched out toward Mr. Haqqani. The photo did not surface in the Chinese news.

Mostly, Beijing wants a stable Afghanistan and the return of several hundred Uyghurs, the Muslim minority that has faced mass detentions in China, said Sajjan M. Gohel, international security director of the Asia-Pacific Foundation, a research group.

The Taliban have offered little, least of all on the Uyghurs, Mr. Gohel said.

“Wang Yi and Beijing may come to painfully realize that the Haqqanis operate to further their own strategic and ideological interests and not China’s,” he said.