NATO Expansion – The Budapest Blow Up 1994

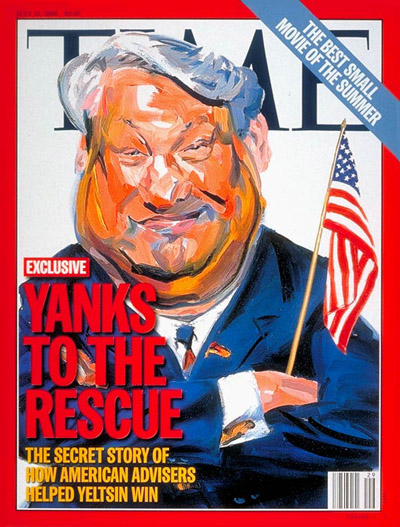

Washington, D.C., November 24, 2021 – The biggest train wreck on the track to NATO expansion in the 1990s – Boris Yeltsin’s “cold peace” blow up at Bill Clinton in Budapest in December 1994 – was the result of “combustible” domestic politics in both the U.S. and Russia, and contradictions in the Clinton attempt to have his cake both ways, expanding NATO and partnering with Russia at the same time, according to newly declassified U.S. documents published today by the National Security Archive.

The Yeltsin eruption on December 5, 1994, made the top of the front page of the New York Times the next day, with the Russian president’s accusation (in front of Clinton and other heads of state gathered for a summit of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, CSCE) that the “domineering” U.S. was “trying to split [the] continent again” through NATO expansion. The angry tone of Yeltsin’s speech echoed years later in his successor Vladimir Putin’s famous 2007 speech at the Munich security conference, though by then the list of Russian grievances went well beyond NATO expansion to such unilateral U.S. actions as withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and the invasion of Iraq.

The new documents, the result of a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit by the National Security Archive, include a series of revelatory “Bill-Boris” letters in the summer and fall of 1994, and the previously secret memcon of the presidents’ one-on-one at the Washington summit in September 1994. Clinton kept assuring Yeltsin any NATO enlargement would be slow, with no surprises, building a Europe that was inclusive not exclusive, and in “partnership” with Russia. In a phone call on July 5, 1994, Clinton told Yeltsin “I would like us to focus on the Partnership for Peace program” not NATO. At the same time, however, “policy entrepreneurs” in Washington were revving up the bureaucratic process for more rapid NATO enlargement than expected either by Moscow or the Pentagon,[1] which was committed to the Partnership for Peace as the main venue for security integration of Europe, not least because it could include Russia and Ukraine.[2]

The new documents include insightful cables from U.S. Ambassador to Moscow Thomas Pickering, explaining Yeltsin’s new hard line at Budapest as the result of multiple factors. Not least, Pickering pointed to “strong domestic opposition across the [Russian] political spectrum to early NATO expansion,” criticism of Yeltsin and his foreign minister, Andrei Kozyrev, as too “compliant to the West,” and the growing conviction in Moscow that U.S. domestic politics – the pro-expansion Republicans’ sweep of the Congressional mid-term elections in November 1994 – would tilt U.S. policy away from taking Russia’s concerns into account.

Pickering was perhaps too diplomatic because there was plenty of blame to go around on the U.S. side. Clinton wrote in his memoir, “Budapest was embarrassing, a rare moment when people on both sides dropped the ball….”[3] Actually, the drops were almost all in Washington. White House schedulers led by chief of staff Leon Panetta tried to prevent Clinton from even going to Budapest by constraining his window there to eight hours, which meant no time for a one-on-one with Yeltsin. Clinton himself thought he was doing Yeltsin a big favor by even coming and expected good press from the substantial reduction in nuclear arsenals that would result from the signing of the Budapest memorandum on security assurances for Ukraine (violated by Russia in 2014). National Security Adviser Tony Lake gave Clinton a prepared text that “was all yin and no yang – sure to please the Central Europeans and enthusiasts for enlargement, but equally sure to drive the Russians nuts….” The author of that phrase, Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott, wasn’t even in Budapest, paying attention to the Haiti crisis instead (“never again” he later wrote, would he miss a Yeltsin meeting).[4]

The new documents include a previously secret National Security Council memo from Senior Director for Russia Nicholas Burns to Talbott, so sensitive that Burns had it delivered by courier, describing Clinton’s reaction to Budapest as “really pissed off” and reporting “the President did not want to be used any more as a prop by Yeltsin.” At the same time, Burns stressed, “we need to separate our understandable anger on the tone of the debate with [sic] Russia’s substantive concerns which we must take seriously.” Similarly, the Pickering cables recommended using Vice President Al Gore’s previously scheduled December trip to Moscow for meetings with Prime Minister Victor Chernomyrdin to also meet with Yeltsin, calm down the discussion, and get back on a “workable track.”

Mending fences would include Gore’s description to Yeltsin of the parallel NATO and U.S.-Russia tracks as spaceships docking simultaneously and very carefully,[5] and Gore and then Clinton assuring the Russians (but not in writing, as Kozyrev kept asking for) that no NATO action on new members would happen before the 1995 Duma elections or the 1996 presidential elections in Russia.

The final assurance was Clinton’s agreement (despite Russia’s brutal Chechen war and multiple domestic pressures) to come to Moscow in May 1995 for the 50th anniversary celebrations of the victory over Hitler. In Moscow, Yeltsin berated Clinton about NATO expansion, seeing “nothing but humiliation” for Russia: “For me to agree to the borders of NATO expanding towards those of Russia – that would constitute a betrayal on my part of the Russian people.” But Yeltsin also saw Clinton would do whatever he could to ensure Yeltsin’s re-election in 1996, and that mattered the most to him. Only after that Moscow summit would Yeltsin order Kozyrev to sign Russia up for the Partnership for Peace.

The new documents only reached the public domain as the result of a Freedom of Information lawsuit by the National Security Archive against the State Department, seeking the retired files of Strobe Talbott. Thanks to excellent representation by noted FOIA attorney David Sobel, State set up a schedule of regular releases to the Archive over the past three years. The full corpus of thousands of pages covering the entire 1990s will appear next year in the award-winning series published by ProQuest, the Digital National Security Archive, which won Choice Magazine’s designation as an “Outstanding Academic Title 2018.” The Archive also benefited from State’s assignment of veteran reviewer Geoffrey Chapman to the task of assessing the Talbott documents for declassification. Chapman ranks among the most thorough, expert, and professional declassifiers in the U.S. government.

The Documents

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

On the eve of the G-7 summit in Naples, Yeltsin presents Clinton with his maximum hopes for the U.S.-Russian partnership and Russia’s place in the transition from G-7 to G-8. The Russian president writes as if his country is already a full G-8 member (the “political” G-8 was just created, mainly as a symbolic gesture to keep Yeltsin engaged). Yeltsin sees the U.S.-Russian partnership playing the key role in the G-8, in fact transforming it from, in his view, purely a symbol into a truly effective organization in international security. He outlines several areas where the U.S.-Russian partnership would “set the pace and the thrust” of G-8 work: Bosnia, European Security, peacekeeping, non-proliferation and North Korea. For European security he proposes an omnibus solution: “While leaving a key role to CSCE, we ought to move toward such a model which would co-opt in a natural way the European Union, the Council of Europe, NATO, the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, the West European Union, and the C.I.S.” Here he is really grasping for any structure other than NATO. But the key to this all, the center of world politics, as Yeltsin would say later, is the partnership between Russia and the U.S., the two superpowers.

Jul 5, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department

Clinton calls Yeltsin before departing for Poland and the Baltics several days before they would meet at the G-7 summit in Naples. The purpose of this call is to allay Yeltsin’s worries about the U.S. president’s meetings with Russia’s former allies, among whom the Poles in particular have been pushing for early and fast NATO expansion. Yeltsin asks him to mention the issue of Russian minorities in the Baltics. Clinton summarizes what he intends to tell the Poles on NATO, but his wording is very careful. Instead of talking about NATO expansion, he quotes himself from back in January 1994, saying that “NATO’s role will eventually expand,” but setting no timetable. It is somewhat misleading because Clinton tells his Russian counterpart: “I would like us to focus on the Partnership for Peace program so that we can achieve a united Europe where people respect each other’s borders and work together.” To Yeltsin this sounds exactly like what he heard in October 1993 from Warren Christopher and Strobe Talbott—Partnership for Peace rather than NATO expansion. Clinton also notes that their partnership is working well—another theme that Yeltsin is eager to hear. However, Clinton’s understanding of the word “partnership” seems to be very different from Yeltsin’s.

Sep 27, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department

Just hours before the Washington summit, Talbott provides detailed talking points on what and how to tell Yeltsin about the main issues on the agenda. The guidance is based on a long conversation the night before with Washington’s most trusted Russian interlocutor, Deputy Foreign Minister Georgy Mamedov, whose advice has always proven to be prescient and helpful before. According to Talbott, Mamedov was “as worried as I’ve ever seen him about the interaction of Russian and American domestic politics.” On NATO, he suggests assuring Yeltsin that Russia remains a key actor whose interests will be taken into account, “a key participant in the process of building new structures in Europe;” that it is a project in which the two countries are “joined” together; and that the U.S. goal is “integration—resisting the temptation to create new divisions, or recreating old ones.” The memo represents a fascinating combination of empathy and condescension toward Russia.

Sep 28, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department

On the second day of the Washington summit, after discussion of the whole spectrum of security issues, Clinton reassures Yeltsin again about NATO expansion in this “one-on-one” with Strobe Talbott as notetaker. Clinton follows the script proposed by Mamedov through Talbott pretty closely, asserting that he has never said that Russia could not be considered for membership, and that “when we talk about NATO expanding, we are emphasizing inclusion, not exclusion.” Clinton says his priority is European unity and security, that he would not spring any surprises on Yeltsin, and that it would take years to bring East European countries up to the requirements and for other members to say yes. Most importantly for Yeltsin, the U.S. president reiterates that “NATO expansion is not anti-Russian; it’s not intended to be exclusive of Russia and there is no imminent timetable.” Talbott contrasts the position of German Defense Minister Volker Ruehe, who said “never” to Russian membership in NATO, to that of Defense Secretary William Perry. Yeltsin says “Perry is smarter than Ruehe” for saying “we are not ruling it out.”

Nov 2, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

This letter is all about the coveted strategic partnership between Russia and the United States, “on the basis of equality,” which remains Yeltsin’s top priority and Russia’s “strategic choice.” He writes: “There should exist a basic understanding that Russian-American partnership constitutes the central factor in world politics.” A month before the CSCE summit in Budapest, the Russian president mentions some “emerging discords,” probably based on what Moscow has been hearing about the discussions on NATO in Washington. For him, the key to overcoming discord is maintaining a high level of trust and careful consideration of the partner’s point of view. Yeltsin is ready to cooperate with Clinton on Bosnia, North Korea, and Ukraine (he is very forthcoming on his support for Ukraine, claims a great relationship with President Leonid Kuchma, and is ready to sign a document on security guarantees for Ukraine in Budapest). Yeltsin ends the letter with another appeal for a fullest “practical equal partnership,” and is eager to meet Clinton in Budapest, where they would talk “first of all about transforming European stability structures.” Yeltsin believes they have “mutual understanding” of this partnership.

Nov 28, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

Two days before the NATO meeting in Brussels, Clinton gives Yeltsin more reassurance about their partnership and the process of NATO expansion. The letter states: “I would like to reassure you now that what the NATO allies do at the upcoming North Atlantic Council (NAC) session in Brussels will be fully consistent with what you and I discussed in the White House during your visit.” Clinton tells Yeltsin that the conversation at the NAC will be not about the list of potential new NATO members or the timetable, but about working out a “common view on precepts for membership,” which will be subsequently presented “to all members of Partnership for Peace who want to receive it.” Expanding NATO would be “intended to enhance the security and promote the integrity of Europe as a whole” rather than “being directed at any country.” The letter notes that now, after Ukraine’s Rada has ratified accession to the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which will allow full removal of nuclear weapons from Ukraine, Clinton is ready to meet with Yeltsin and the presidents of Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan and to provide security assurances to those countries. The careful distinction is between the “guarantees,” which Yeltsin said he was ready to sign, and the word “assurances” that the U.S. insisted on using.

Nov 30, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

In this very short letter on the eve of the CSCE summit in Budapest and the day before the NAC meeting, Yeltsin reiterates what he thinks is a common understanding regarding CSCE and NATO based on his conversations with Clinton in Washington and subsequent correspondence. CSCE will play a key role in European security, and it needs more than a cosmetic renovation—a transformation into a “full-fledged European organization with a sound legal base.” On NATO: “We have agreed with you that there will be no surprises, that first we should pass through this phase of partnership, whereas issues of further evolution of NATO should not be decided without due account to the opinion and interests of Russia.” Yeltsin warns Clinton very specifically that “[a]doption of an expedited time-table, plans to start negotiations with the candidates already in the middle of the next year will be interpreted, and not only in Russia, as the beginning of a new split of Europe.” Yeltsin’s and Kozyrev’s information from Washington and the European capitals certainly included rumors of an expedited schedule of NATO expansion.

Dec 2, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

The NAC communiqué on December 1, 1994, announcing a study of requirements for NATO accession to be completed in 1995, must have sounded to Yeltsin like exactly what he was warning against. The study would be finished in November, just before the Duma elections, contributing to Yeltsin’s growing electoral vulnerability. In Brussels, Kozyrev, upon reading the language of the communiqué, refused to sign the Partnership for Peace documents, concluding that the communiqué proclaimed that “partnership is subsidiary to enlargement.” He also relayed his understanding to Yeltsin in a phone call.[6] Now, two days before the start of the Budapest summit, all Clinton’s efforts to mollify and reassure Yeltsin are on the brink. In a last-ditch attempt to preserve peace and calm at the summit, Clinton sends his Russian partner this letter, hoping to persuade him that this was simply a misunderstanding of the NAC communiqué on the part of Kozyrev. Clinton says he was “surprised and disappointed” by the foreign minister’s actions. The letter emphasizes that since the Clinton-Yeltsin meeting in Washington, “we have adhered assiduously to the principles on which you and I agreed: no surprises; high priority on maintaining—and strengthening—the U.S.-Russia partnership; and careful, inclusive deliberations taking a full account of the opinion and interests of Russia”—but clearly this is not how it felt in Moscow.

Dec 3, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

Immediately responding to the U.S. president’s letter, Yeltsin writes: “I cannot agree with your appraisal of this document,” meaning the NAC communiqué. He believes that the present misunderstanding requires more specific explanations. Clinton’s restatement of their understandings achieved in Washington is very important for Yeltsin, and a broader U.S.-Russian partnership is his top priority. He wants the president to provide “assurances that enlargement rather than partnership is not being emphasized now.” He also wants to engage in dialogue on “specific obligations and security guarantees for Russia and NATO.” In the Russian view, the only acceptable way to enlarge NATO is if the alliance is effectively rendered “new and transformed through partnership.” The American delegation to Budapest, in the absence of Strobe Talbott, missed the warnings here.

Dec 6, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

In this prescient and very carefully worded NODIS cable, Ambassador Thomas Pickering gives his analysis of Kozyrev and Yeltsin’s behavior and their reaction to the NAC communiqué. He cites several causes that explain the blowup; among them Kozyrev’s personal sensitivities, domestic opposition, and the feeling that the U.S. is pushing harder for NATO expansion than other NATO countries (and harder than they have admitted to the Russians). He points correctly to the strong opposition to NATO expansion across the entire Russian political spectrum and the support that tough speeches have received at home. The Russian leadership perceived that the U.S. was telling different things about NATO expansion to its Western allies and Russia (true). Pickering’s recommendations are not to pick a fight with Yeltsin but to give him assurances and mend fences during the upcoming Gore visit to Moscow—telling Yeltsin explicitly that there would be no decisions on expansion before the Russian election in June 1996 and no new members before the end of the century.

Dec 6, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

This immediate follow-up cable to Document 10, above, provides specific advice for preparing Gore’s visit and his meeting with Yeltsin. It is based on a candid conversation with Georgy Mamedov and the latter’s previous long conversation with Kozyrev. Pickering thinks “it would be particularly important to lean as far forward as we can in reassuring Yeltsin that we envisage no actual decisions on new members before June of 1996, and no formal entry of new members until considerably after that.” Clinton should send Yeltsin a letter listing specific assurances and follow up with a personal message with the vice president. Gore’s visit would be the best chance to get the NATO discussion on “a workable track.”

Dec 6, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

Nick Burns sends this very sensitive and candid memo to Talbot personally by courier. Talbott missed Budapest because of his involvement in the crisis in Haiti, was partially blaming himself for the blowup, and now has to pick up the pieces. The memo is based on Burns’ revealing conversations with Clinton on the plane and back in Washington. Burns describes Clinton as feeling “really pissed off,” that Yeltsin had “showed him up” with his public criticisms of U.S. policy, and that “his anger grew when we returned to Washington” and saw how events were being treated in the news. National Security Adviser Tony Lake said Clinton “did not want to be used any more as a prop by Yeltsin.” At the same time, the memo shows Clinton’s sincere desire to do it right and his search for a way to square the circle—expand NATO and preserve a great relationship with the reforming Russia. Clinton wonders “whether or not we should try to be more frank with the Russians” about the U.S. vision on expansion and its timetable. Importantly, even while being mad at Yeltsin for “dumping on us in public,” Clinton understands that “we must also deal with Russia’s real and legitimate security concerns about NATO expansion.” Burns expresses doubts about Talbott’s Mamedov channel because he did not give the U.S. any warning of what Kozyrev and Yeltsin were planning to say. Talbott’s note in the margin suggests Mamedov did not have that information himself.

Dec 12, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

This letter, initially drafted by Nick Burns, extends the hand of reconciliation to Yeltsin but does not go as far in specific assurances as proposed by Pickering in his earlier cable (Document 10). Clinton lays out his vision of a “unified, stable and peaceful Europe in the next century.” Still, the letter deemphasizes NATO expansion as a Clinton administration priority by putting it after “strengthened CSCE” in the list of U.S. priorities. To outline an appealing scenario, the letter lists all the Western institutions that Russia would become a part of, including the World Trade Organization, the Paris Club, and the G-7. Clinton states: “Our common aim should be to achieve a full integration between Russia and the West—including strengthened links with NATO—with no new divisions in Europe.” The letter expresses Clinton’s view that the U.S. has adhered scrupulously to the pledge of “no surprises.” He is appealing to Yeltsin to keep their trusting relationship and to discuss this “most difficult issue that you and I will confront together” confidentially rather than publicly.

Dec 24, 1994

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

Greatly relieved by the successful visit to Russia by Vice President Gore, Clinton sends this letter to Yeltsin reiterating his “strong commitment both to the U.S.-Russia partnership and to the goal of a stable, integrated and undivided Europe” and restating the September commitment that “the future development of NATO will proceed gradually and openly.” Having left this “rift” behind, the U.S. and Russia can now concentrate on substantive discussions about the “most important and sensitive question” of European security. Clinton pledges that he will “continue to take the lead to ensure that a strong Russian economic program is accompanied by large-scale Western support.” And above all—what Yeltsin wants to hear most—the letter is filled with occurrences of the word “partnership” and praise for what this partnership had achieved so far. In other words—a lot of nice generalities but no candid or specific message on NATO expansion. The great irony of this letter is that it was sent just three days after Defense Secretary Perry found out at the December 21 debriefing session with Gore that the president was committed to a rapid expansion of NATO right after 1996, rather than taking the much slower route through the Partnership for Peace, which was Perry’s preferred option.[7]

Apr 8, 1995

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

This NODIS “eyes only” cable presents a detailed account of a two-hour lunch (one-on-one, no notetakers) Talbott had with the Russian foreign minister, Andrei Kozyrev. The context of this conversation is very important—the Russian military is trying to “clean up” Chechnya before the May summit. Some of the most cruel operations in the Chechen war took place in April 1995 (see “The Massacre in Samashki”), but this issue does not figure even once over the course of two hours. The conversation is instead fully devoted to the issue of NATO expansion. Talbott’s goal was to persuade the Russian foreign minister to sign the Partnership for Peace documents before the summit in May. According to the cable, Kozyrev “launched into a monologue that lasted over an hour.” This monologue presented the most thorough account of the Russian position on NATO. Kozyrev mentioned that Yeltsin was currently finishing a letter to Clinton on European security and was hoping for a response with concrete written assurances about NATO expansion. Kozyrev asked for a “letter that avoids vague, evasive language” and states that there will be no rush to enlargement and that the PFP will be “for real” and “at the center of things for the next 2-3 years.”

But that is unacceptable for Talbott, who well knows that the train has already left the station. Kozyrev describes the domestic context he has to deal with—the “military-industrial people are infuriated” because the U.S. is moving into East European markets and selling their equipment; nobody, not even liberals, understands “why [NATO] is moving its borders toward Russia” (even his arch-rival, Vladimir Lukin, is becoming critical); and that “the stimulus for partnership has to a large extent been killed by enlargement.” He draws a sharp contrast between the PFP (“you and us”) and enlargement (“us versus them”).

Kozyrev points to the key moment when the misunderstandings started: Christopher’s visit to Moscow in October 1993 to inform the Russians about the Partnership for Peace. At that meeting, “Yeltsin reacted so favorably in part because he thought PFP was an ‘alternative’ to NATO expansion.” But in his view, “with enlargement going forward, everything about PFP is ruined for us.” With this conversation, Talbott realizes that the upcoming summit will not be a walk in the park, but at the same time it becomes even more crucial that Clinton come to Moscow to clear the air in person, get the Russians to sign the PFP, and arrive at some modus vivendi with Yeltsin on the issue of NATO expansion.

Apr 15, 1995

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

This very candid memo is the result of Strobe Talbott’s conversations in Moscow. It shows that he understands the Russian position on NATO expansion extremely well and appreciates the difficulty the president will face at the summit in Moscow. Unwittingly, though, Talbott’s memo points to the biggest problem—the president’s “determination to keep on track two strategies that are crucial to [his] vision of post Cold War Europe: admitting new members to NATO and developing a parallel security relationship between the Alliance and Russia.” These two strategies will prove irreconcilable in the end.

The memo walks Clinton through the main events on the road to NATO expansion so far: the trip to Europe in January 1994, the Washington Summit with Yeltsin in September 1994, and the “cold peace” blowup in Budapest in December, trying to provide explanations for Yeltsin’s actions in his domestic context. But despite all the empathy for Yeltsin’s predicament, the U.S. answer, the memo says, is “that the NATO expansion track will proceed even if the Russians refuse to permit progress on the NATO-Russia track.” Therefore, the president should try to persuade Yeltsin that it is in his interest to cooperate and sign the PFP papers. Talbott repeats to Clinton that there is strong opposition to NATO expansion across the political spectrum in Russia, but he believes that Yeltsin is so interested in a good summit and in integration with the West that “he has a strong personal motive for trying to square the circle—and for doing so at the Summit.” The NATO allies also want to see a good NATO-Russia relationship and a good summit because “there is nothing more offensive than a Russian on the defensive.”

The memo is a good representation of Clinton’s priorities at the moment and, in contrast to his communications with Yeltsin, the CSCE and other “new” European security structures are not even mentioned.

Apr 26, 1995

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

In this long conversation, Christopher tries to persuade Kozyrev to sign the PFP documents before the May 10 summit and links the signing to further progress on NATO-Russia cooperation and to assurances that could be given to Russia regarding NATO expansion at the NAC ministerial at the end of May. Kozyrev reiterates the Russian concerns that he explained to Talbott in their meeting in Moscow (Document 15) and complains about the heated rhetoric about NATO expansion that is harmful to any progress on this issue. Kozyrev states that Russia will never endorse a hasty NATO expansion and compares it with an avalanche. Christopher promises to tone down the rhetoric and to try to impress that on the Polish leadership as well. Kozyrev implies that Lech Walesa is the problem here and that he expects the Polish leader to state immediately after the NAC ministerial that Poland is ready to join NATO in the nearest future. Kozyrev tells the Americans how much blood he has spilled in trying to advance the PFP in Russia to no avail. This depressing conversation does not lead to any conclusion or resolution, but it does clearly point to the fact that any U.S.-Russian understanding regarding NATO expansion could only be achieved at the highest level, and the time for that would come on May 10.

May 10, 1995

Freedom of Information Lawsuit. State Department.

This long and wide-ranging conversation is remarkable as a glimpse into the Bill-Boris relationship. Yeltsin is very appreciative that Clinton has come to Moscow to celebrate the 50th anniversary of victory in World War II despite significant opposition in the United States. Here, he presents his real cri de coeur on NATO. He sees “nothing but humiliation” for Russia if NATO expands, calling it a “new encirclement.” He argues that what they need is a new European security system, not old blocs. He says emotionally, “for me to agree to the borders of NATO expanding toward those of Russia—that would constitute a betrayal on my part of the Russian people.”

In response, Clinton patiently and clearly explains the U.S. position on NATO expansion—it should be seen in the context of continuing U.S. involvement in European security and an effort to create a fully integrated Europe. He hints at trade-offs if Yeltsin accepts NATO expansion—Russia would be a founding member of the post-COCOM regime, join the G-7, have a special relationship with NATO—but only if Russia “walk[s] through the doors that we open for you.” Yeltsin’s urgent priority is the upcoming elections; he confides in the U.S. president that his “position heading into 1996 elections is not exactly brilliant.” He asks the president to postpone the expansion discussion at least until after the election. Clinton is very straightforward about his own electoral pressures with the Republicans and voters in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Ohio pushing for NATO expansion.

Yeltsin eventually agrees reluctantly to Clinton’s offer—no NATO decisions until after elections are over, only a study of expansion; but also no anti-NATO rhetoric from Russia and an agreement to sign the PFP before the end of May. Yeltsin needs Clinton’s support to win at the polls and he sees no alternative to relying on the American’s assurances.

Notes

[1] See especially James Goldgeier, Not Whether But When: The U.S. Decision to Enlarge NATO (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1999), pp. 69-76, for a detailed interview-based account of the inside game, some of which showed up in contemporaneous media accounts and op-ed debates noticed by Moscow.

[2] For Secretary of Defense William Perry’s deep regrets that the U.S. chose NATO expansion over continuing with the Partnership for Peace, see his memoir, My Journey at the Nuclear Brink (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015), pp. 116-129.

[3] Bill Clinton, My Life (New York: Knopf, 2004), pp. 636-637.

[4] For Clinton’s promise to Yeltsin, see Strobe Talbott, The Russia Hand: A Memoir of Presidential Diplomacy (New York: Random House, 2002), p. 137; for “all yin and no yang,” p. 141; for “never again,” p. 142.

[5] For Gore’s talking points, see Svetlana Savranskaya and Tom Blanton, “NATO Expansion: What Yeltsin Heard,” National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 621, March 16, 2018, Document 16. Gore said any NATO expansion would be gradual, open, and not in 1995 “when you’ll have parliamentary elections.” The spaceship metaphor is in Strobe Talbott, The Russia Hand, p. 144.

[6] Strobe Talbott, The Russia Hand, p. 140.

[7] A forthcoming book by Johns Hopkins professor Mary Sarotte, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), argues that the Clinton “shift” against the Partnership for Peace dramatically raised the “cost per inch” of NATO expansion, and contributed to the current tension and stalemate in U.S.-Russia relations. See M.E. Sarotte, “Containment Beyond the Cold War: How Washington Lost the Post-Soviet Peace,” Foreign Affairs, November-December 2021.