Dear Committee members,

I’m working with a co-author on the following paper reporting our recent research in Russia and the U.S., and I thought that the members of this group would be an ideal source of feedback and constructive criticism before submitting it

for publication. We were lucky to find a company in Ukraine willing to risk violating Russian and Ukrainian laws on wartime propaganda by administering this survey in Russia, but such research is particularly hard to do nowadays – half a dozen Russian companies

turned us down. So you may find the data itself interesting for whatever insight it can provide into comparative Russian and U.S. public opinion.

More importantly, I was hoping that one or more of you might find this worthwhile enough to read (or skim), and offer any constructive criticism you may have of any part. If so – first, thank you in advance – would you please send me your

feedback in a direct email to pbeattie@cuhk.edu.hk?

We applied a method often used in psychological research, but which hasn’t been much used in political psychology or (even less – never – as far as I can tell) political science. So we spent more space than usual in describing the method,

which hopefully is comprehensible. As, I hope, the whole paper is… but that determination I’ll leave up to anyone with the time and inclination to read this draft (not for circulation), and offer whatever comments you may have. Advice on framing/presentation

is most welcome, as this is an emotionally charged issue, and social scientists are hardly immune from making judgments on the basis of ideological preferences.

With no further ado, I’m copying the draft text below, and attaching the appendix to this email. All feedback is much appreciated!

All the best,

Peter

Abstract

This paper investigates and compares the accuracy of, and bias in, knowledge relevant to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, within the U.S. and Russia. Taking an interdisciplinary approach by applying signal

detection theory as it has been used in psychology, we measured the extent to which the two populations could correctly identify accurate and inaccurate statements related to dominant political narratives explaining the war in the U.S. and Russia. The results

indicate that both groups have more accurate knowledge pertaining to the dominant narrative in the opposing country, compared to the dominant narrative in their own country. Both groups evinced greater bias toward their own-country narrative, with Russians

substantially more biased than U.S. Americans. The paper discusses how these results are connected to differences and similarities in the two countries’ media systems and political contexts. It also considers implications of these results for the formation

of public opinion about the Russia-Ukraine war. Normative implications differ; from a classical realist international relations perspective, public ignorance is expected and largely irrelevant, but some versions of democratic theory require a degree of unbiased

and accurate knowledge found absent here.

Significance Statement

What mass publics know about foreign affairs is of great importance in international politics. Knowledge, disinformation, and ignorance probabilistically delimit the range of opinions one is likely to

form on a foreign affairs issue. Military strategists understand the importance of “information warfare”, since publics apply foreign affairs knowledge to form opinions, which may help or hinder a government’s foreign policy goals. However, little research

has been done to explore what the Russian and U.S. publics know about the invasion of Ukraine. By using a signal detection technique to assess the accuracy of, and bias in, knowledge related to the war in Ukraine, this study provides insight into the knowledge

both publics bring to bear in forming opinions about the conflict.

Main Text

Introduction

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 considerably escalated a violent conflict between the states, especially after the

2014 annexation of Crimea (1). As of writing, recent estimates of civilian casualties include over 6,000 killed and nearly 10,000 injured, though these are likely significant undercounts (2). Over seven million people in Ukraine have become refugees, leading

to the biggest refugee crisis in Europe since WWII (3). Politically sensitive estimates of military casualties vary widely, from nearly 6,000 Russian military personnel killed (4) to over 50,000 killed and 160,000 wounded (5), and from 9,000 Ukrainian military

personnel killed by the end of August (6) to 14,000 killed toward the end of March alone (7). Longer-term, the war threatens to slow economic growth worldwide and increase hunger in poor countries (8), and interrupt progress on climate action (9). It also

poses the risk of nuclear war (10).

Modern information warfare includes attempts to manipulate the information mass publics use to form political opinions, thereby influencing

voting decisions, support for foreign policies, and other forms of political behavior (11). Information warfare in the Russia-Ukraine war is ongoing, with successful Ukrainian propaganda operations focused on Europe and the U.S. to ensure support from Western

democracies, and Russian propaganda efforts focusing primarily on shoring up support internally and in the Global South, often framing the conflict as “the West vs. the Rest” (12). A key premise of information warfare is that public opinion – and the information

mass publics use to form opinions – has major military implications. If shaped according to strategic objectives, public opinion can facilitate policies preferred by leadership (e.g., mobilization) and impede disfavored policies (e.g., making concessions in

peace negotiations). In extreme cases, it may lead to regime change.

This study was designed to investigate what Russian and U.S. publics know about the conflict leading up to the Russian invasion: the

basic historical facts comprising key elements of competing narratives explaining, justifying, or condemning the invasion. We selected Russia, a belligerent and the aggressor, and the United States, the largest provider of military, humanitarian, and financial

assistance to Ukraine (13). Knowledge related to the conflict, and the opinions that are constructed out of this knowledge, are of particular consequence to the war in these two countries. As of writing, U.S. public opinion is strongly pro-Ukrainian and in

favor of U.S. military assistance (14), and indications of Russian public opinion suggest high public support for the “special military operation” (15).

Political information is primarily provided by the news media, and national media systems are often compared for their effects on public

knowledge of politics (16). Despite the proclamation of extensive guarantees for free speech and press and the ban on censorship in Russia of the early 1990s, journalism was soon reduced to a weapon in the “information wars” fought by the Russian tycoons (17).

The state information monopoly established in the country under Putin supported the regime’s vertical power structure (18), discrediting alternative news and opinions (19). At the invasion’s onset, the Russian government shut down the remaining independent

media in Russia, completing the return of the Russian media system into an organ of state propaganda, censorship, and disinformation.

Although the U.S. media system is relatively closer to the ideal of a free press facilitating a democratic public sphere, it suffers

from commercial biases (20, 21), source bias (22), and exclusion of dissenting views, particularly on foreign policy (23-25). Without top-down control as in Russia, a range of structural and psychological pressures exert their own influence on media content,

jointly comprising a form of “censorship with American characteristics” in the U.S. mass media (26).

Using signal detection to assess political knowledge

Signal detection theory (SDT) has been used in a wide variety of applications (27). In psychology, SDT surveys include binary choices (e.g.,

true/false) to calculate signal (true hits) and noise (false alarms) distributions, providing measurements of response bias (criterion scores, or

c) and accuracy/sensitivity (d-prime, or d’), which help distinguish motivated reasoning from knowledge accuracy. For example, SDT was applied to investigate the causes of knowledge deficits that impede successful treatment for schizophrenic patients

(28). Using a checklist of symptoms caused by either stress or schizophrenia, schizophrenic patients displayed lower knowledge accuracy (lower

d’) and greater bias (higher c, indicating motivated denial) than a control group. These results suggested that clinicians need to supplement educational efforts with help on patients’ motivation and coping strategies.

SDT has also been used in political psychology. Closer to the present study, researchers applied SDT to investigate whether accurate knowledge

of past racism would be greater in ethnic-minority than -majority communities, and would partly account for differences between the two groups in their perception of racism in contemporary events (29). Their survey instrument was split between true instances

of past racist incidents and fabricated incidents resembling actual ones. Their Afro-American participants demonstrated significantly more accurate knowledge of historical racism than Euro-American participants (a higher

d’), and this greater “reality attunement” mediated Afro-Americans’ more acute perception of contemporary racism, both systemic and individual. That is, Afro-Americans’ more accurate knowledge of historical racism made them better able to detect contemporary

instances of racism than Euro-American participants, separate from the knowledge gained from personal experiences.

This illustrates an important point: knowledge (or information, defined as that which reduces uncertainty) is essential for political judgment

(30). Without accurate knowledge of the history of racism in the U.S., for instance, it is more difficult to recognize present instances of racism. One could suppose that the racial wealth gap is caused by racism, somehow; but to conclude so with certainty

and precision is more likely when one is informed of the history of employment, housing, and credit discrimination against Afro-Americans. This information makes manifest historical continuities that would otherwise be invisible.

Knowledge and ignorance, information and disinformation, are the foundation of political judgments. As such, examples are endless.

Public support for banning chlorofluorocarbons would not have existed without knowledge of their effects on ozone, and the ozone layer’s role in protecting life on earth (31). Misinformation and disinformation can play a no less powerful role. Misinformation

was a key cause of the Iraq War, the source of consequential misperceptions among U.S. elites (32) and the public (33).

The Present Study

The present study applies SDT to investigate the accuracy of, and bias in, knowledge relevant to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, within

the U.S. and Russia. This is important because political narratives – our understandings of and opinions on issues, which influence our political actions – comprise facts, or bits of information, whether true or false (34). Bits of politically relevant information

are usually absorbed as parts of broader narratives, rather than individually, at random. Social psychologists in one research tradition call these “social representations,” and have studied how similar mental representations of various phenomena are spread

by the media and other means of communication until they are so widely shared as to be properly “social” (35). By testing for accuracy and bias in issue-specific knowledge, we can gain insights into the narratives (based on the information comprising them)

to which a population has been exposed. This is a coarser-grained version of Moscovici’s idea of leveraging individual terms, like a radioactive “tracer” used in medicine, to detect the circulation of much broader social representations throughout a society

(36).

Our SDT instrument (see Appendix A) was designed to include key facts used within dominant narratives in the U.S. and Russia during

February-April, 2022 to explain and justify each government’s policies amid the invasion. These narratives were “dominant” in the sense that they were promulgated by political elites and mass media outlets in the U.S. and Russia, respectively crowding out

or completely excluding contrary narratives. We selected well-documented facts at the core of these narratives, like the United Nations Secretary General condemning the invasion as illegal under international law (part of the dominant U.S. narrative), and

the U.N. estimate of deaths caused by the civil war in eastern Ukraine since 2014 (part of the dominant Russian narrative). We created false items from real-world disinformation (e.g., claims in the Russian media that U.S.-funded biological warfare laboratories

in Ukraine were developing bioweapons targeting Slavic genetic profiles), exaggerating documented facts (e.g., the extent of U.S. military assistance to Ukraine before the invasion), and fabrications that might be found plausible to the underinformed (e.g.,

that Putin wrote an op-ed in 1999 calling for reconstituting the Russian Empire). We finalized our SDT instrument after soliciting input and feedback from colleagues. It consisted of 20 items, evenly split between the dominant U.S. and Russian narratives;

half of each set were “true”, in the sense that given currently available information they were not seriously, or in good faith, contestable as worded; half were “false”, either considerable exaggerations of actual facts or completely fabricated. (Here and

in Appendix A, items are labeled with “US” and “R” respectively referring to U.S. and Russian narratives, “T” is true and “F” is false, and are numbered 1 through 5.)

During the first months of the invasion, the dominant narrative we identified in Russia about the war is that it is merely a "special

military operation" to protect ethnic Russians in eastern Ukraine (1RT, 1RF, and 4RT are related to this point; subsequent labels are related to the points they follow), “demilitarize” a growing security threat on its borders (3RF, 5RF, 5RT), and “denazify”

the Ukrainian government. The Ukrainian and Russian peoples are joined together in brotherhood, and most of the Ukrainian population recognizes this; but the Ukrainian government is a puppet of the U.S. (3RT, 3RF), controlled by neo-Nazis (2RT, 2RF). Therefore,

the Russian Federation's special military operation is not a war of aggression condemned around the world (4RF), but a justified effort to protect the Russian ethnic minority in Ukraine, remove neo-Nazis from their positions of political power over historically

Russian territories, and ensure that Ukrainian territory is not used by the U.S. and NATO as a military staging ground for troops and offensive weaponry that would represent a grave national security threat for Russia.

The dominant early narrative we identified in the U.S. about the war is that it is an illegal act of aggression under international

law (1UST), motivated not by the Russian government's stated concerns over NATO expansion (5UST, 1USF, 3USF) or "denazifying" Ukraine (2UST), but rather by Russian nationalist revanchism seeking to regain territories formerly part of the Russian empire (3UST,

2USF), and by Putin's fear of democracy in Ukraine which threatens his preferred authoritarianism (4USF). The Russian government's claims cannot be taken seriously, because NATO does not threaten Russia (3USF) - and Putin himself once recognized that before

he began to use the NATO-expansion excuse for his own aggression (5UST, 1USF). The charge of neo-Nazi influence is preposterous, since Ukraine has a Jewish president and far-right political parties are not widely popular in Ukraine (2UST). Russia is a rogue,

aggressive state that ignores international law and the norms of the international community (1UST, 4UST, 5USF). The U.S. government did not exacerbate tensions with Russia; the best explanation for Russia's invasion is Putin's authoritarianism, aspirations

to rebuild the Russian empire, and fear of democracy spreading close to his borders.

To develop an understanding of which early narratives about the war were dominant in the U.S. and Russia, we drew from mass media outlets

and statements from high-ranking politicians (Appendix A). This process – as with all scientific inquiry – is unavoidably influenced by the authors’ own knowledge, values, and beliefs; what philosopher of science Miriam Solomon calls “decision vectors”, an

epistemically neutral term for all factors that influence the direction or focus of scientific decisions (37). As both authors condemn the invasion as a war crime of aggression, our inclusion criterion decisions may have overlooked key information that may

have been obvious to a scientist holding the opposite opinion, along with other possibilities.

Aspects of the Russian and U.S. media systems – the Russian system’s subordination to the imperatives of the government, and the U.S. system’s tendency

to give minimal foreign affairs coverage “indexed” to opinions of domestic political elites and lacking dissenting perspectives – influenced our expectations. Russian citizens are more likely to encounter the dominant Russian narrative in their media diets

(and more likely to accept arguments placing their national in-group in a positive light and enemy out-groups in a negative light), and U.S. citizens are more likely to encounter the dominant U.S. narrative in their media diets (and more likely to accept arguments

matching their intergroup bias). Therefore, we anticipated that Russian participants would have less accurate knowledge relating to the dominant Russian narrative than U.S. participants; and that U.S. participants would have less accurate knowledge relating

to the dominant U.S. narrative than Russian participants. (That is, Russian participants would have a lower

d' for Russian narrative items than U.S. participants, and U.S. participants would have a lower

d’ for U.S. narrative items than Russian participants.) We also expected Russian participants to exhibit greater response bias in favor of the Russian narrative than U.S. participants (a higher

c), and U.S. participants to exhibit greater response bias in favor of the U.S. narrative than Russian participants, indicating motivated reasoning.

Interpreting SDT measures

SDT measures of response bias and accuracy cannot reveal

precisely what people in either country believe about, or how they understand, the war. In the most limited interpretation, these measures uncover the level of accuracy and bias in knowledge of the items included, within the samples tested. The broader

interpretation is the same one commonly used to interpret “political knowledge” scales in political science research (38, 39): the greater the knowledge of basic civics facts tested in standard political knowledge scales, the more likely it is that one also

has a wealth of other politically relevant knowledge. (While it is possible that one’s political knowledge could be entirely limited to such basic civics facts, skewing “political knowledge” scores derived from these scales, it is unlikely; more likely is

that the tested facts are learned incidentally while accumulating larger stores of information on political developments and debates.) Likewise, the greater the accuracy (ability to distinguish true from false items) and the lesser the bias (tendency to label

items supporting one’s own side “true” and vice versa) in knowledge of the items tested here, the more likely it is that one has a much greater store of accurate and unbiased knowledge on the background to the war. Precisely what that store of knowledge includes

is impossible to determine, outside of the tested items – just as with interpretations of standard political knowledge batteries.

Furthermore, accuracy in knowledge of the tested items does not

determine opinions on the war, as nearly any imaginable opinion could be made consonant with accurate knowledge of the tested items, in the presence of certain auxiliary beliefs. One might be able to perfectly distinguish true from false among all public

statements Putin has made, and still support the invasion for geopolitical reasons, anti-Ukrainian prejudice, accelerationist ideologies, etc. Similarly, one could have been an early supporter of the invasion of Iraq who accurately dismissed claims of WMD

and al Qaeda links, and favored war for the goal of strengthening U.S. influence in the region or spreading democracy, etc.

The relevance of knowledge accuracy is that its opposite – ignorance or disinformation – probabilistically delimits the range of opinions

one can form on an issue. For example, one might have held pacifist moral commitments, but having only misinformation about Iraqi WMD and close Iraqi ties to the terrorists who carried out the 9/11 attacks – and lacking information contradicting such claims

– one’s options were probabilistically limited to a courageous (or reckless) commitment to pacifism in the face of a seemingly existential threat, or making an exception to pacifist principle in response to exceeding peril. Similarly today, a Russian opponent

of Putin and his ideology, who has absorbed a significant amount of disinformation in the media about “genocide” in eastern Ukraine and no information challenging such claims, is more likely limited to accepting them but rejecting the government’s reaction

in favor of some alternative, or choosing the “lesser evil” by supporting a purported humanitarian intervention. Hence knowledge (in)accuracy does not determine opinions, but it does affect the likelihood of arriving at some opinions over others – and engaging

in political (in)action accordingly.

Results

Assessed as a simple true-false 20-item quiz, Russian participants did marginally better than U.S. participants, with an advantage of nearly one-half correct response on average (Russians:

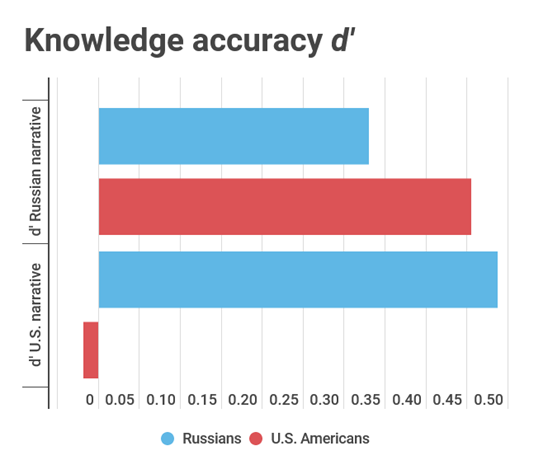

M = 11.41, SD = 2.04; U.S. Americans: M = 10.96, SD = 1.84; t(2379) = 5.65, P < 0.001). Our SDT measures reveal more significant differences (Figures 1 and 2). As expected, U.S. participants exhibited greater knowledge accuracy than Russian participants on

items relating to the dominant Russian narrative (U.S. Americans: M = .45, SD = .74; Russians: M = .33, SD = .79; t(2379) = 3.96, P < 0.001). Contrariwise, Russian participants exhibited greater knowledge accuracy than U.S. participants on items relating to

the dominant U.S. narrative (Russians: M = .49, SD = .88; U.S. Americans: M = -.02, SD = .75; t(2379) = 15.05, P < 0.001). That is, U.S. participants were better able to accurately sort true from false in the dominant Russian narrative than Russians themselves,

and Russian participants were better able to accurately sort true from false in the dominant U.S. narrative. Russian participants also indicated significantly higher confidence in their answers on a 1-10 scale (M = 6.60, SD = 2.21) than U.S. participants (M

=4.70, SD = 1.79; t(2379) = 23.10, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Knowledge accuracy,

d’,

for U.S. and Russian participants

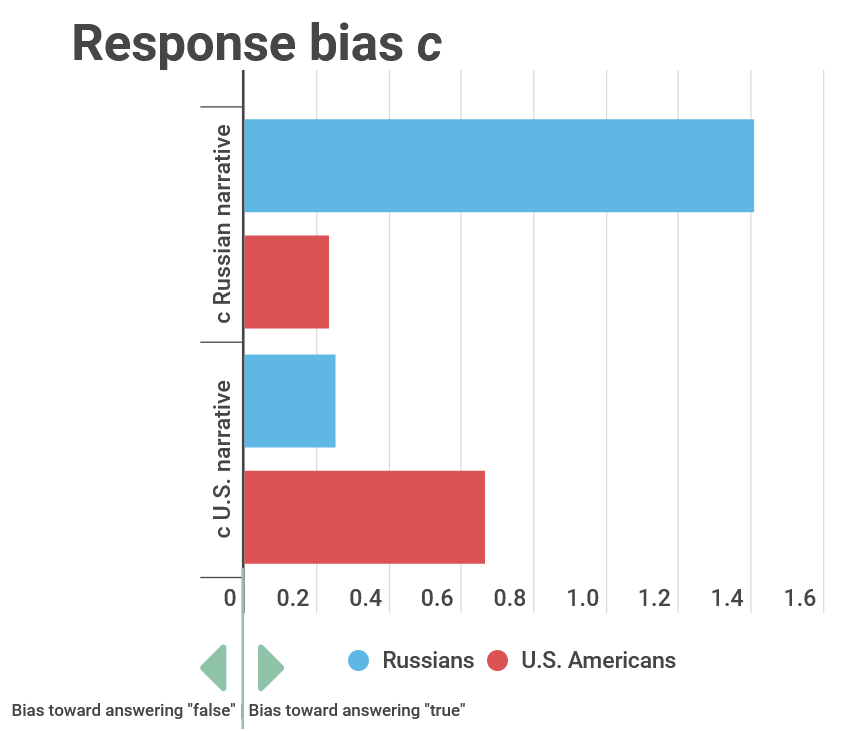

Criterion (c) scores indicate the expected patterns of response bias between the two samples. U.S. participants had a greater tendency to answer “true” to items representing the dominant U.S. narrative

(U.S. Americans: M = .66, SD = .81; Russians: M = .25, SD = .91; t(2379) = 11.59, P < 0.001), while Russian participants had a much greater tendency to answer “true” to items representing the

dominant Russian narrative (Russians: M = 1.40, SD = 1.00; U.S. Americans: M = .23, SD = .92;

t(2379) = 29.58, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Knowledge bias,

c,

for U.S. and Russian participants

These aggregate results can be examined more closely by looking at differences in individual items. Russian participants performed significantly better recognizing the five RT statements as true (Russians:

M = 4.37, SD = 1.07; U.S. Americans: M = 3.22, SD = 1.27; t(2379) = 23.16, P < 0.001), but significantly worse recognizing the five RF statements as false (P < 0.001), except for the item concerning the UN General Assembly vote, where they were indistinguishable

from U.S. participants (P = .311). The U.S. sample’s knowledge accuracy suffered from outperforming the Russian sample on only one of the UST statements: the UN Secretary General condemning the invasion as illegal under international law (P < .001). The two

samples performed equally well classifying statements on the low percentage of the vote won by far-right parties in the last Ukrainian election, Putin’s claim that Lenin and the Bolsheviks created Ukraine by severing Russian land, and a list of recent internal

and external wars the Russian Federation has fought. Unexpectedly, 55% of the Russian sample correctly classified as true the statement that in 2000 Putin expressed openness to Russia joining NATO and difficulty in imagining NATO as an enemy, compared with

47% of the U.S. sample (P < .001). The Russian sample outperformed the U.S. sample in correctly classifying all of the USF statements as false (at the P < .001 level, except for one: 47% of Russian and 43% of U.S. participants correctly labeled “false” that

until 2008 no prominent Russian politicians opposed former Soviet countries joining NATO, since none considered the alliance to pose a security threat [P = .053]).

To examine relationships between knowledge accuracy and opinions on the war, we asked both samples two questions on their war-related opinions. The Russian sample was asked to rate agreement with whether

Russia should stay the course in its special military operation, and whether Russia should use its full military power without restrictions to achieve its war aims; the U.S. sample was asked to rate agreement with whether the U.S. should enforce a no-fly zone

in Ukraine, and whether the U.S. military should enter the war against Russia. Averaging their responses as a measure of militaristic policy preferences, Russian respondents’ preference for militarism in Ukraine was positively related to accurate knowledge

of the U.S. narrative (r[1009] = .18, P < .001), but negatively related to accurate knowledge of the Russian narrative (r[1009] = -.22, P < .001). U.S. respondents’ preference for militaristic policies was negatively, weakly related to overall knowledge accuracy

(r[1350] = -.09, P = .002), knowledge of the Russian narrative (r[1350] = -.07, P = .012), and non-significantly to knowledge of the U.S. narrative (r[1350] = -.04, P = .154).

Discussion

Our results indicate that neither the U.S. nor the Russian public have been exposed to a range of narratives, the factual information comprising them, and

open debate between proponents of competing narratives that would provide accurate knowledge of the background to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This result few may find surprising regarding Russia – its government has long waged a “war against reality”

(40), exercising “the raw power of criminal law enforcement, surveillance by security forces, censorship by its media regulator, and legal and extralegal demands against internet platforms” (41). Its media system, now more than ever since the dissolution

of the USSR, resembles the Soviet one, as a mouthpiece of state propaganda and disinformation serving the interests of the political elite. The effects are clear in our data: a population confident in their beliefs related to the war, but unable to separate

truth from fiction in their government’s narrative.

The U.S. media system shares few of the pathologies of its Russian counterpart. Commercial media have not been brought under state control by a domineering

executive, and freedom of speech and of the press are still protected rights in U.S. jurisprudence. However, media scholars have long noted a lack of ideological diversity internal to the most-used outlets in the U.S. (42), although the internet offers no

shortage of ideological diversity for those with the skills and inclination to construct their own diverse media diet. While we know of no recent comparative media content analyses of Ukraine war coverage, a recent poll of the U.S., U.K., Poland, Germany,

and Brazil found that U.S. media audiences were the least likely to perceive a wide range of different perspectives on the war in their media (only 1/3rd did so) (43). In our data, instead of looking like well-informed democratic citizens to Russia’s

propagandized authoritarian subjects, U.S. participants, in key respects, formed a mirror image of their Russian counterparts: much more effective at discerning truth from fiction concerning the foreign narrative, but worse at doing the same regarding the

dominant narrative in their own country. However, as would be expected in a relatively more open media system, the U.S. sample evinced lesser bias toward their own country’s dominant narrative.

Nonetheless, we did not predict the significantly greater bias from Russian participants toward their in-group narrative, compared to U.S. Americans. Why

might the population of autocratic Russia have more accurate knowledge of facts in the U.S. narrative than U.S. Americans have toward the Russian narrative; and why, despite this greater accuracy, are Russians considerably more biased towards the narrative

dominant in the Russian state media and propaganda system? Providing coverage of the opposing side’s narrative, specifically to challenge it, may be an effective strategy to harden public opinion against this narrative; particularly in the digital era, when

controlling information flows on the Internet, with widely available tools to circumvent media censorship, make total erasure of opposing narratives effectively impossible. Recent interview-based research with pro-war Russians suggests that state propaganda

related to the war in Ukraine mostly “challenges alternative information [i.e., competing narratives about the war], instead of providing false facts” (45). Offering weak versions of an opponent’s arguments and then providing evidence to discredit them, would

represent a disturbing real-world application of “attitude inoculation” from research in political psychology (46). Such a strategy may not only help governments discredit critics, but also distract from internal problems by providing a seemingly considerable

diversity of perspectives. Collecting information may be part of a strategy to cope with stress, anxiety, fear, and humiliation that many Russians experience, as surveys of public opinion in Russia show (48). However, under a prolonged state of stress, individuals

may be particularly vulnerable to emotional manipulation, e.g., appeals to patriotism, which in Soviet culture often meant loyalty towards the government, notably during WWII (44). Collecting and interpreting war-related information may help the population

find rationalizations to avoid discomfort and responsibility. While these results were expected due to features of the two countries’ media systems, influences on the development of political perspectives and opinions arise from the “demand side” as much as

the media system’s “supply side” (26). Psychological pressures, like intergroup bias or system justification tendency, affect which ideas – among those offered from the media’s supply – are more likely to be accepted as true. Therefore, knowledge accuracy

can be influenced both by a supply of in/accurate information from the media, selective exposure to ideologically congenial media sources, and a desire to believe some information to be true and others false, due to intergroup bias, system justification, spiral

of silence dynamics, and other psychological influences. Additionally, the bias of Russians and Americans toward narratives demonizing the other country may be reinforced by the historical memory of the Cold War ideological confrontation between the capitalist

United States and the communist Soviet Union. For instance, a recent study of public opinion in Russia found a widespread belief that the Russian state currently wages war against the U.S., rather than Ukraine (47).

Much depends on how these SDT measures are interpreted. A radically limited interpretation would be that these results reveal the level of accuracy and bias

in knowledge only of the included items, within the samples tested. But this reasoning would also apply to, and effectively invalidate, the significantly narrower political knowledge measurements used in a great deal of public opinion and political behavior

research. A broader interpretation, much the same as used to interpret standard political knowledge measures, is that these measures of knowledge accuracy and bias serve as a proxy for a great deal of related information not included within the survey. Paradoxically,

the limited interpretation may in fact require a greater leap of faith: that information relevant to explaining the war is randomly distributed, not connected in narratives that are disseminated via the media and peer-to-peer, such that accurate knowledge

of the tested items has no relationship to accurate knowledge of related items (and vice versa with inaccurate knowledge).

Normative implications of the study’s results differ widely. From a classical realist perspective, the results may be heartening. The public is not to be trusted to make

wise decisions on foreign policy, so their proper role is to support whatever decisions are made by their informed and responsible leadership (49). From this perspective, the U.S. and Russian publics are appropriately informed, able to see through their enemy’s

narrative, but credulous concerning the narrative propounded by their own country’s leadership. But who guards the guardians, or how is it ensured that a country’s leadership is informed and responsible in its foreign policy decisions? From a liberal democratic

perspective, these results indicate a problem. The people are to guard the guardians, and ensure that their leaders are informed and responsible; but if the people are poorly informed, they cannot play this role effectively.

Without accurate and unbiased knowledge of factual information necessary to construct narrative understandings of the war, citizens are probabilistically limited in the

policy preferences that follow from their understandings. For instance, a Russian citizen with accurate knowledge related to the dominant U.S. narrative, but less accurate and more biased knowledge related to the dominant Russian narrative, is less likely

to develop a preference for ending the war because they believe that ethnic Russians in Ukraine face genocide, and neo-Nazi extremists and quislings of U.S. empire dominate the Ukrainian government, posing a national security threat to the homeland. While

it is certainly possible that they may develop anti-war preferences regardless, a lack of accurate knowledge regarding these alleged threats makes it more likely that one would support a humanitarian intervention to eliminate them. Similarly, a U.S. citizen

with the equivalent knowledge deficiency is less likely to adopt a preference for, among other possibilities, diplomatic negotiations to end the war. The evidence available in the court of their minds is limited to supporting the explanation that Putin is

motivated by vast imperial ambitions, and there is none to suggest that his behavior is consistent with traditional great power politics, with more limited security aims that might be accommodated through diplomacy. Without privileging any one narrative, or

labeling one “true” and another “false”, the issue here is only that ignorance should not play a determinative role in the development of political opinions, no matter the result. Insofar as public opinion should be free to develop autonomously, out of a multitude

of tongues, these knowledge deficits are problematic (50).

Even for those in the U.S. and Russia who believe that their government’s policies have been correct may have cause for concern. Certainly, if one supports a given policy,

then propaganda that generates public support for that policy may seem like an unalloyed good, regardless of the false beliefs such propaganda may create (51). But if the population is left with demonstrably inaccurate beliefs on matters of fact, they are

relatively more vulnerable to counterpropaganda that highlights such inaccuracies to persuade targets to adopt the opposite belief – compared to those with the same narrative understanding and opinion, but who have accurate knowledge of these matters of fact.

Materials and Methods

SDT measures. The survey instrument began with a notice that all answers would be provided at the end (to reduce

cheating), followed by the knowledge test. Applied to the responses to our true-false items, D-prime, or d’, measures the distance between the signal (true hits, or true items correctly labeled) and noise (false alarms, or false items labeled true) means in

standard deviation units (for calculations and further detail, see 52). Positive d’ scores indicate a progressively greater ability to distinguish true from false items, 0 indicates a complete inability to distinguish true from false items, and negative scores

suggest inaccurate knowledge or response confusion. Criterion scores, or c, measure response bias in standard deviation units. They were calculated so a positive c indicates a bias in favor of answering “true”, a value of 0 indicates no bias, and negative

c indicates a bias in favor of answering “false.”

Both

d’ and c were calculated separately for U.S. and Russian narrative categories (comprising only the five true and five false items for each country). U.S.- and Russia-specific

d’ measures accuracy of knowledge related to dominant U.S. and Russian narratives, respectively, and U.S.- and Russia-specific

c measure bias toward answering true or false to all items reflecting dominant narratives in either country. Response bias in country-specific

c scores help explain overall knowledge (in)accuracy, whether due to motivated reasoning (more likely when knowledge accuracy is relatively low) or an ideologically biased store of information (more likely when knowledge accuracy is relatively high).

Demographics. Two online survey and market research companies were employed to obtain quota samples of 1,000

respondents each in the U.S. and Russia, using panel and river sampling methods, with quotas matching major demographic categories in the two countries. Studies of this method of sampling have found it to be less representative than random digit dialing, but

with reference to demographic characteristics unlikely to be related to levels of political knowledge, however (53). In the U.S., demographic quotas included age, sex, ethnicity, education, income, and region, according to their percentage of adults over 18

in the latest census. (Due to a lack of participants without a high school diploma in the sample, we weighted the data according to latest census figures.) In Russia, demographic quotas included age, sex, region, and size of settlement, and weighted according

to the latest census figures. 90.7% claimed that they were of Russian ethnicity, 2.2% were Tatar, and the remaining 7.1% reported other ethnicities or mixed family composition. The highest level of education was secondary for 15.4%, secondary vocational for

30.5%, some college for 6.1%, bachelor’s degree for 24.7%, and specialty, master’s, or academic degrees, and other postgraduate studies for 23.2%. 18.4% reported a monthly income of up to ₽18k, 16.7% between ₽18-25k, 31.2% between ₽25-49k, 15.7% between ₽50-74k,

8.4% between ₽75-99k, 5% between ₽100-149k, and 4.5% over ₽150k. As no differences emerged between weighted and unweighted data on the comparisons of interest, we reported results from weighted data here.

References

-

Center for Preventative Action, Conflict in Ukraine (2022).

Global Conflict Tracker. Available at https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Ukraine: civilian casualty update 31 October 2022 (2022).

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Available at https://www.ohchr.org/en/news/2022/10/ukraine-civilian-casualty-update-31-october-2022

(Accessed 8 November 2022).

-

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Ukraine refugee situation (2022).

Operational Data Portal - Ukraine Refugee Situation. Available at https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

A. Marokhovskaya, I. Dolinina, Война в цифрах (2022).

IStories. Available at https://istories.media/reportages/2022/05/16/voina-v-tsifrakh/

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

Armed Forces of Ukraine, Russia’s losses (2022). Available at

https://www.minusrus.com/en (Accessed

15 September 2022).

-

Ukrinform, На війні загинули майже 9 тисяч українських героїв – Залужний (2022). Available at

https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-ato/3555675-zaluznij-rozpoviv-pro-pekelnu-obstanovku-na-fronti.html

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

AFP, Ukraine conflict death toll: what we know (2022).

France 24. Available at https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220413-ukraine-conflict-death-toll-what-we-know

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

P.-O. Gourinchas, War dims global economic outlook as inflation accelerates (2022).

IMF Blog. Available at https://blogs.imf.org/2022/04/19/war-dims-global-economic-outlook-as-inflation-accelerates/

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

S. Braun, Ukraine war threatens climate targets (2022).

Deutsche Welle. Available at https://p.dw.com/p/4CvHf

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

G. D. Arceneaux, R. Tecott, Nuclear risks: Russia’s Ukraine war could end in disaster (2022).

The National Interest. Available at https://nationalinterest.org/feature/nuclear-risks-russia%E2%80%99s-ukraine-war-could-end-disaster-203889

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

H. Lei, Modern information warfare: analysis and policy recommendations

Foresight 21: 4, 506-522 (2019).

-

C. Bronk, G. Collins, D. Wallach, Cyber and information warfare in Ukraine: what do we know seven months in? (2022).

Baker Institute for Public Policy. Available at https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/cyber-and-information-warfare-ukraine-what-do-we-know-seven-months

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

A. Antezza, A. Frank, P. Frank, L. Franz, I. Kharitonov, B. Kumar, E. Rebinskaya, C. Trebesch, Ukraine Support Tracker (2022).

Kiel Institute for the World Economy. Available at https://www.ifw-kiel.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker/

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

F. Newport, What We Know About American Public Opinion and Ukraine (2022).

Gallup News (March 22). Available at https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/390866/know-american-public-opinion-ukraine.aspx

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

Levada Centre. Konflikt s Ukrainoj: ijul' 2022 goda (2022).

Levada Centre Website (August 1) Available at

https://www.levada.ru/2022/08/01/konflikt-s-ukrainoj-iyul-2022-goda/

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

T. Aalberg, J. Curran, Eds.,

How media inform democracy: A comparative approach (Routledge, 2012).

-

O. Koltsova,

News media and power in Russia (Routledge 2006).

-

E. Vartanova, "The Russian media model in the context of post-Soviet dynamics" in

Comparing Media Systems Beyond the Western World, D.C. Hallin & P. Mancini Eds. (Cambridge, 2012), pp. 119-142.

-

E. Sherstoboeva, “Regulation of Online Freedom of _expression_ in Russia in the Context of the Council of Europe Standards” in

Internet in Russia: Societies and Political Orders in Transition, S. Davydov Eds. (Springer, 2020), pp. 83-100.

-

R. W. McChesney,

The Political Economy of Media: Enduring Issues, Emerging Dilemmas (NYU Press, 2008).

-

J.E. Uscinski,

The People's News: Media, Politics, and the Demands of Capitalism (NYU Press, 2014).

-

P. Manning,

News and News Sources: A Critical Introduction (SAGE, 2001).

-

W. L. Bennett, Toward a Theory of Press‐State

Relations in the United States. Journal of Communication 40(2) (1990).

-

J. Pedro, The propaganda model in the early 21st century (part I & ii).

International Journal of Communication, 5, 1865–1926 (2011).

-

J. Zaller, D. Chiu, Government's little helper: US press coverage of foreign policy crises, 1945–1991.

Political Communication, 13(4), 385-405, (1996).

-

P. Beattie,

Social Evolution, Political Psychology, and the Media in Democracy: The Invisible Hand in the U.S. Marketplace of Ideas (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

-

H. Stanislaw, Signal Detection Theory and its Applications.

Oxford Bibliographies (2018).

-

A. W. Wong, C. Y. Chiu, J. W. Mok, J. G. Wong, E. Y. Chen, The role of knowledge and motivation in symptom identification accuracy among schizophrenic patients: Application of signal

detection theory. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45(3), 427-436 (2006).

-

J. C. Nelson, G. Adams, P. S. Salter, The Marley hypothesis: Denial of racism reflects ignorance of history.

Psychological Science, 24(2), 213-218 (2013).

-

S.L. Althaus, Information effects in collective preferences.

American Political Science Review, 92(3), 545-558 (1998).

-

A. Egelston, “Protecting the Ozone Layer” in:

Worth Saving,” AESS Interdisciplinary Environmental Studies and Sciences Series. (Cham: Springer, 2022).

-

C.A. Duelfer, S.B. Dyson, Chronic misperception and international conflict: The US-Iraq experience.

International Security, 36(1), 73-100 (2011).

-

S. Kull, C. Ramsay, E. Lewis, Misperceptions, the media, and the Iraq war.

Political Science Quarterly, 118(4), 569-598 (2003).

-

P. Beattie,

Social Evolution, Political Psychology, and the Media in Democracy: The Invisible Hand in the U.S. Marketplace of Ideas (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), pp. 17-62.

-

W. Wagner, N. Hayes,

Everyday Discourse and Common Sense: The Theory of Social Representations

(Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

-

S. Moscovici,

Social Representations: Explorations in Social Psychology (NYU Press, 2001), p. 158.

-

M. Solomon,

Social Empiricism (MIT Press, 2001).

-

M.X. Delli Carpini, S. Keeter,

What Americans Know about Politics and Why It Matters (Yale University Press, 1996).

-

A. Lupia,

Uninformed: Why People Know So Little About Politics and What We Can Do About It (Oxford University Press, 2016).

-

P. Pomerantsev,

This is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality (PublicAffairs, (2019).

-

D. Kaye, Online Propaganda, Censorship and Human Rights in Russia's War Against Reality.

AJIL Unbound, 116, 140-144 (2022).

-

M.P. Porto, Frame diversity and citizen competence: Towards a critical approach to news quality.

Critical Studies in Media Communication, 24(4), 303-321 (2007).

-

K. Eddy, R. Fletcher, Perceptions of media coverage of the war in Ukraine (2022).

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available at https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2022/perceptions-media-coverage-war-Ukraine

(Accessed 8 November 2022).

-

M. Edele, Fighting Russia's history wars: Vladimir Putin and the codification of World War II.

History and Memory, 29(2), 90-124 (2017).

-

Svoboda,

“Shok, somnenie i molchanie. Rossijane i vojna v Ukraine” (2022, 12 Septneber). Availiable at

https://www.svoboda.org/a/shok-somnenie-i-molchanie-rossiyane-i-voyna-v-ukraine/32028600.html

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

M. Pfau, D. Roskos-Ewoldsen, M. Wood, S. Yin, J. Cho, K.H. Lu, L. Shen, Attitude accessibility as an alternative explanation for how inoculation confers resistance.

Communication Monographs, 70(1), 39-51 (2003).

-

Meduza, “Vojti vo mrak i nashhupat' v nem ljudej Pochemu rossijane podderzhivajut vojnu? Issledovanie Shury Burtina”

(2022, 24 April). Available at https://meduza.io/feature/2022/04/24/voyti-vo-mrak-i-naschupat-v-nem-lyudey

(Accessed 15 September 2022).

-

Svoboda,

“Shok, somnenie i molchanie. Rossijane i vojna v Ukraine” (2022); Meduza, “Vojti vo mrak i nashhupat' v nem ljudej Pochemu rossijane podderzhivajut vojnu? Issledovanie Shury Burtina”

(2022).

-

H. Morgenthau,

Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace (6th edition). (Alfred A. Knopf, 1985).

-

United States v. Associated Press, 52 F. Supp. 362 (S.D.N.Y. 1943).

-

M. Lee, “Propaganda for War” in:

Propaganda and American Democracy, N. Snow, Ed., pp. 94-119 (LSU Press, 2014).

-

H. Stanislaw, N. Todorov, Calculation of signal detection theory measures.

Behavior research methods, instruments, & computers, 31(1), 137-149 (1999).

-

B. MacInnis, J.A. Krosnick, A.S. Ho, M.J. Cho, The accuracy of measurements with probability and nonprobability survey samples: Replication and extension.

Public Opinion Quarterly, 82(4), 707-744 (2018).

Peter Beattie

Assistant Professor; Assistant Programme Director, MSSc in Global Political Economy

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

+852 3943 9794

Social Evolution, Political Psychology, and the Media in Democracy:

The Invisible Hand in the U.S. Marketplace of Ideas

(Palgrave Macmillan, 2019)

https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030028008