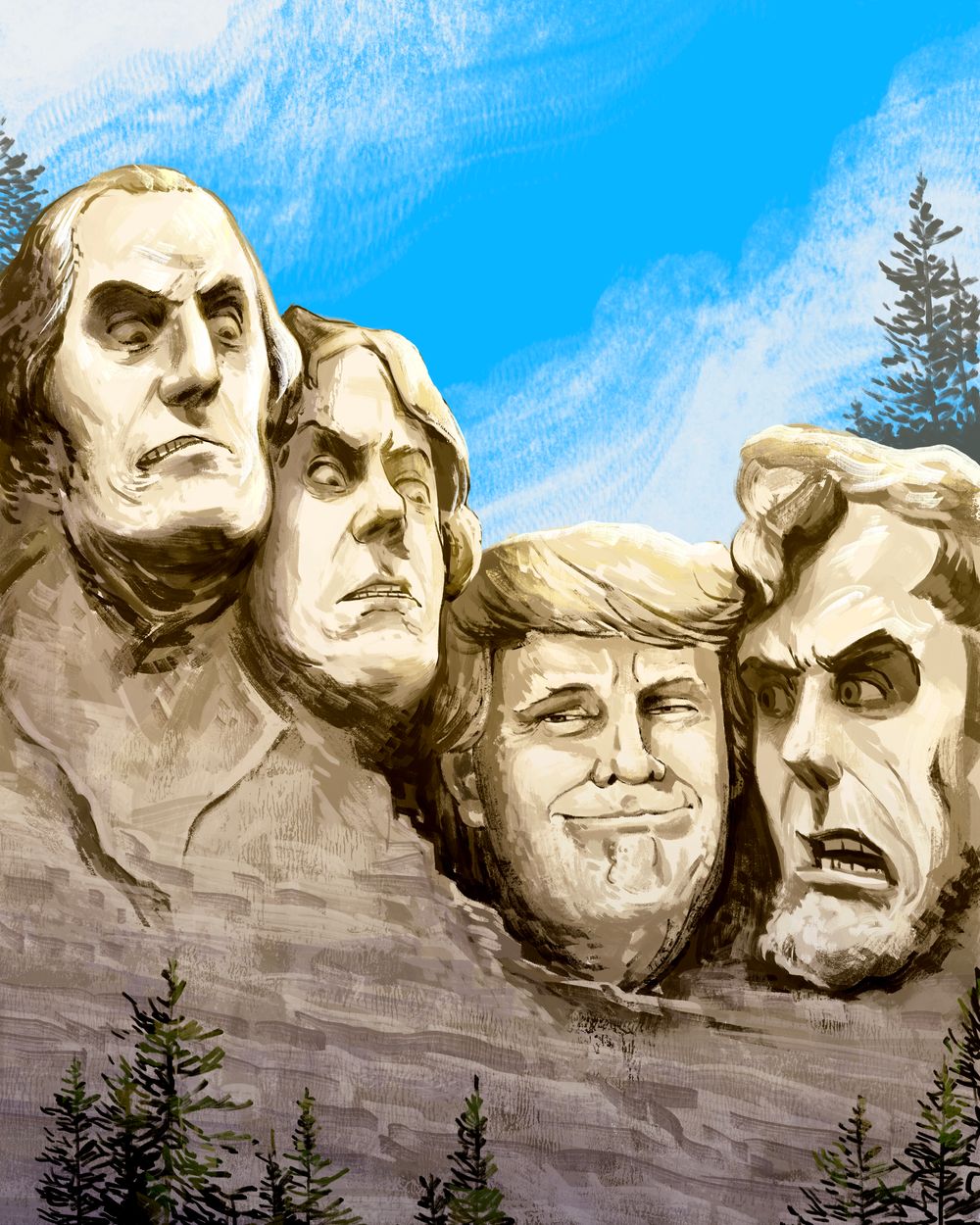

The Founders Anticipated the Threat of Trump

This week’s indictment of the former president outlines the sort of demagogic challenge to the rule of law that the Constitution’s architects most feared

The allegations in the indictment of Donald Trump for conspiring to overturn the election of 2020 represent the American Founders’ nightmare. A key concern of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton was that demagogues would incite mobs and factions to defy the rule of law, overturn free and fair elections and undermine American democracy. “The only path to a subversion of the republican system of the Country is, by flattering the prejudices of the people, and exciting their jealousies and apprehensions, to throw affairs into confusion, and bring on civil commotion,” Alexander Hamilton wrote in 1790. “When a man unprincipled in private life, desperate in his fortune, bold in his temper…is seen to mount the hobby horse of popularity,” Hamilton warned, “he may ‘ride the storm and direct the whirlwind.’”

The Founders designed a constitutional system to prevent demagogues from sowing confusion and mob violence in precisely this way. The vast extent of the country, Madison said, would make it hard for local factions to coordinate any kind of mass mobilization. The horizontal separation of powers among the three branches of government would ensure that the House impeached and the Senate convicted corrupt presidents. The vertical division of powers between the states and the federal government would ensure that local officials ensured election integrity.

And norms about the peaceful transfer of power, strengthened by George Washington’s towering example of voluntarily stepping down from office after two terms, would ensure that no elected president could convert himself, like Caesar, into an unelected dictator. “The idea of introducing a monarchy or aristocracy into this Country,” Hamilton wrote, “is one of those visionary things, that none but madmen could meditate,” as long as the American people resisted “convulsions and disorders in consequence of the acts of popular demagogues.”

According to the federal indictment issued this week, President Trump attempted to overturn the results of the 2020 election by conspiring to spread such “convulsions and disorders” through a series of knowing lies. The indictment alleges that soon after election day, Trump “pursued unlawful means of discounting legitimate votes and subverting the election results,” perpetuating three separate criminal conspiracies: to impede the collection and counting of the ballots, Congress’s certification of the results on Jan. 6, 2021, and the right to vote itself.

The indictment alleges that all three conspiracies involved a concerted effort by Trump and his co-conspirators to subvert the election results using “knowingly false claims of election fraud.” In particular, Trump allegedly “organized fraudulent slates of electors in seven targeted states”; tried to use “the power and authority of the Justice Department to conduct sham election crime investigations”; tried to enlist Vice President Mike Pence “to fraudulently alter the election results”; and, as violence broke out on Jan. 6, redoubled his efforts to “convince Members of Congress to further delay the certification.”

‘I do not believe there is anything that approaches this in American history.’

— J. Michael Luttig, former U.S. Court of Appeals judge

In all of these instances, the indictment alleges, Trump’s conspiracy to overturn the election was resisted by principled state and federal officials—including the Republican speaker of the Arizona House, Republican members of his own cabinet and the many state and federal judges who uniformly rejected the false election charges.

Defenders of the indictment argue that special counsel Jack Smith was compelled to seek it in the face of such a grave threat to our democratic institutions. “I do not believe there is anything that approaches this in American history,” former U.S. Court of Appeals judge J. Michael Luttig told me. A respected conservative jurist, Luttig helped to persuade Vice President Pence that he had no power to overturn the election results. “These are the gravest offenses against the United States that an incumbent president could commit,” he said, “save possibly treason.”

By contrast, critics of the indictment argue that, even if Trump did attempt to overturn the election results, his efforts were not illegal as long as he legitimately believed that the election had been stolen. “In order to establish the underlying charges, the government would have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Trump himself actually knew and believed that he had lost the election fair and square,” Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz, who defended Trump in his first impeachment trial, wrote in the Daily Mail. “I doubt they can prove that.” National Review editorialized that even false political speech is protected by the First Amendment: “Assuming a prosecutor could prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Trump hadn’t actually convinced himself that the election was stolen from him (good luck with that), hyperbole and even worse are protected political speech.”

An instructive historical analogy to the Trump case is the controversy involving free speech and election integrity surrounding the election of 1800, which culminated in the treason trial of Aaron Burr. Two years before the election, Federalists in Congress passed the Sedition Act, making it illegal to “write, print, utter or publish…any false, scandalous, and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States.” In practice, this muzzled the Republican opposition by making it a crime to criticize the Federalist president, John Adams.

The Republican vice president, Thomas Jefferson, responded by arguing that states had the power to nullify federal laws with which they disagreed. In the election that followed, Adams came in third, and Jefferson and his vice president, Aaron Burr, tied with an equal number of electoral votes. Alexander Hamilton, who believed that Jefferson posed less of a threat to the republic than Burr, helped persuade Federalists in Congress, who had to break the tie, to elect Jefferson. Both Adams and Burr accepted the election results and supported the peaceful transfer of power.

Once in office, however, Jefferson retaliated against his political enemies. He encouraged state prosecutions of his Federalist critics and lashed out against his archrival, Chief Justice John Marshall. He also supported the impeachment of Justice Samuel Chase, a partisan Federalist who had presided over one of the sedition trials, but the Senate acquitted Chase, establishing a precedent that Congress shouldn’t remove judges from office because of disagreement with their rulings.

Jefferson then indicted Burr, his former vice president, for treason. After killing Hamilton in the famous duel in 1804, Burr had fled west to improve his fortunes and raised an expedition of men to seize lands in Texas and Louisiana belonging to Spain. In 1806, Jefferson received reports that Burr was conspiring to incite the western states to secede from the Union and to conquer new territory. Jefferson alerted Congress and ordered Burr’s arrest.

Partisan passions ran high in 1800, as they do today, but American institutions and norms survived, thanks to the self-restraint of the leading institutional players.

Burr’s treason trial the following year was presided over by Chief Justice Marshall, who was dubious about the indictment. He issued a subpoena to Jefferson to deliver documents that Burr said he needed for his defense. Jefferson initially claimed executive privilege but ultimately turned over the letters. Marshall then told the jury that, according to the Constitution, a treason conviction required evidence of overt acts of war committed against the U.S. proved by two witnesses, and that no such evidence existed. The jury swiftly found Burr not guilty. Jefferson reportedly wanted to bring impeachment charges against Marshall for his conduct in the Burr trial but was dissuaded from doing so by the precedent established by the acquittal of Justice Chase.

Unlike Aaron Burr, Donald Trump has not been indicted for treason. But the trial of Burr, and the legal controversies surrounding the election of 1800, provide lessons about the challenges that will face American institutions before and after the election of 2024. Then, as now, there were grave warning signs of democratic decay, with allegations that both parties were criminalizing their opposition through partisan prosecutions and attacks on free speech, judicial independence and the rule of law.

Partisan passions ran high in 1800, as they do today, but American institutions and norms survived, thanks to the self-restraint of the leading institutional players and their commitment to preserving the Union. Adams and Burr accepted the election results, Jefferson accepted the Burr verdict, and the Republican Congress declined to impeach Marshall.

That institutional self-restraint was shattered in the decades leading up to the Civil War. Abraham Lincoln ran in 1860 as a defender of the Union and the rule of law against the threat of mob violence. Southern states responded to his election by seceding, invoking the same states’ rights arguments that Jefferson had introduced in opposition to the Sedition Acts. The shared norms and constitutional commitments that had prevailed a generation earlier were not strong enough to avert the disaster of war.

The great question today is which of these historical precedents our leaders and the public will follow. Donald Trump faces a range of legal troubles, but the indictment announced this week, even as he dominates the Republican race for the 2024 nomination, is the most far-reaching yet, accusing him of actively undermining foundational elements of our constitutional order.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

What does the latest indictment of Donald Trump say about the strength of our democratic institutions? Join the conversation below.

The challenge for Republicans and Democrats alike will be to join in defending the rule of law and to allow the judicial process to take its course, as happened in the Burr trial. Otherwise, the election of 2024 may turn into a tragic rupture of our institutions, more like 1860 than 1800.

At the end of their lives, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, who had reconciled in the decade after the explosive election of 1800, were pessimistic about the future of the American experiment. Adams worried that American citizens lacked sufficient civic virtue to sustain the republic, and Jefferson feared that factional clashes over slavery would destroy the Union.

Among the Founding generation, only James Madison was moderately optimistic that American institutions would survive. He hoped that public opinion could be educated to overcome the most destructive partisan passions. He had faith that, among other things, a class of enlightened “literati” would use the new technologies of the print media to diffuse the cool voice of reason throughout the land.

In our own polarized age, Madison’s optimism now looks quaint. On social media, with a business model of “enrage to engage,” posts meant to spark our partisan passions travel further and faster than those based on persuasive reason. Democratic transparency and participation have grown in ways that the Founders couldn’t have imagined, extending long-overdue rights and liberties but also levelling the speed bumps they put in place to promote thoughtful deliberation by elites.

The Founders feared direct democracy and devised a Constitution to tame it, to the frustration of reformers today. They would be astonished by our current political system, with its presidential primary system, nationwide campaigning and ever-more sophisticated media targeting, all of which has given new opportunities to partisan extremists and demagogues.

The Founders’ concerns about how democracies fall were articulated by a young Abraham Lincoln in one of his earliest political speeches. Then serving as a member of the Illinois legislature, he worried about the fate of the republic if a leader of demagogic ambition arose who was not committed to the institutions built by the founding generation. “Distinction,” Lincoln said, “will be his paramount object, and although he would as willingly, perhaps more so, acquire it by doing good as harm; yet, that opportunity being past, and nothing left to be done in the way of building up, he would set boldly to the task of pulling down.”

Jeffrey Rosen is president and CEO of the National Constitution Center. His new book, “The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America,” will be published by Simon & Schuster in February.

Copyright ©2023 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Appeared in the August 5, 2023, print edition as 'This week’s indictment of the former president outlines the sort of demagogic challenge to the rule of law that the Constitution’s architects most fear'.