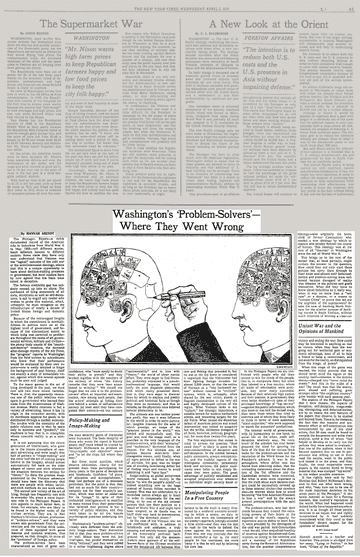

Washington's ‘Problem‐Solvers'—Where They Went Wrong

April 5, 1972, Page 45Buy Reprints

TimesMachine is an exclusive benefit for home delivery and digital subscribers.

About the Archive

This is a digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive, before the start of online publication in 1996. To preserve these articles as they originally appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them.

Occasionally the digitization process introduces transcription errors or other problems; we are continuing to work to improve these archived versions.

The Pentagon Papers—a richly documented record of the American role in Indochina from World War to May 1968—tell different stories, teach different lessons to different readers. Some claim they have only now understood that Vietnam was the “logical” outcome of the cold war or the anti‐Communist ideology, others that this is a unique opportunity to learn about decision‐making processes in government, but most readers have by now agreed that the basic issue raised is deception.

The famous credibility gap has suddenly opened up into an abyss. The quicksand of lying statements of all sorts, deceptions as well as self‐deceptions, is apt to engulf any reader who wishes to probe this material,.which, unhappily, he must recognize as the infrastructure of nearly a decade of United States foreign and domestic policy.

Because of the extravagant lengths to which’ the commitment to nontruthfulness in politics went on at the highest level of government, and because of the concomitant extent to which lying was permited to proliferate throughout the ranks of all governmental services, military and civilian—the phony body counts of the “searchand‐destroy” missions, the doctored after‐damage reports of the Air Force, the “progress” reports to Washington from the field written by subordinates who knew that their performance would be evaluated by their own reports—one is easily tempted to forget the background of past history, itself not exactly a story of immaculate virtue, against which this newest episode must be seen and judged.

To the many genres in the art of lying developed in the past, we must now add two more recent varieties. There is, first, the apparently innocuous one of the public relations managers in government who learned their trade from the inventiveness of Madison Avenue. Public relations is but variety of advertising; hence it has its origin in the consumer society, with its inordinate appetite for goods to be distributed through a market economy. The trouble with the mentality of the public relations man is that he deals only in opinions and “goodwill,” the readiness to buy, that is, in intangibles whose concrete reality is at a minimum.

It is not surprising that the recent generation of intellectuals, who grew up in the insane atmosphere of rampant advertising and were taught that half of politics is “image‐making” and the other half the art of making people believe in the imagery, should almost automatically fall back on the older adages of carrot and stick whenever the situation becomes too serious for ‘theory.” To them the greatest disappointment in the Vietnam adventure should have been the discovery that there are people with whom carrotand‐stick methods do not work either.

The second new variety of the art of lying, though less frequently met with in everyday life, plays a more important role in the Pentagon Papers. also appeals to much better men, to those, for example, who are likely to he found in the higher ranks of the civilian services. They are, in Neil Sheehan's felicitous phrase, professional “problem‐solvers,” and they were drawn into government from the universities and the various think tanks, some of them equipped with game theories and systems analyses, thus prepared, as they thought, to solve all the “problems” of foreign policy.

The problem‐solvers have been characterized as men of great selfconfidence, who “seem rarely to doubt their ability to prevail,” and they worked together with the members of the military of whom “the history remarks that they were ‘men accustomed to winning.'". We should not forget that we owe it to the problemsolvers’ effort at impartial self‐exainination, rare among such people, that the actors’ attempts at hiding their role behind a screen of self‐protective secrecy (at least until they have completed their memoirs—in our century the most deceitful genre of literature) were frustrated. The basic integrity of those who wrote the report is beyond doubt; they could indeed he trusted by Secretary McNamara to produce an “encyclopedic and objective” report and “to let the chips fall where they may.”

But these moral qualities, which deserve admiration, clearly did not prevent them from participating for many years in the game of deceptions and falsehoods. Confident “of place, of education and accomplishment,” they lied perhaps out of a mistaken patriotism. But the point is that they lied not so much for their country—certainly not for their country's survival, which was never at stake—as for its “image.” In spite of their undoubted intelligence—it is manifest in many memos from their pens—they also believed that politics is but variety of public relations, and they were taken in by all the bizarre psychological premises underlying this belief.

Washington's “problem‐solvers” obviously were different from the ordinary image‐makers. Their distinction lies in that they were problem‐solvers as well. Hence they were not just intelligent, but prided themselves on being “rational,” and they were indeed to a rather frightening degree above “sentimentality” and in love with “theory,” the world of sheer mental effort. They were eager to find formulas, preferably expressed in a pseudomathematical language, that would unify the most disparate phenomena with which reality presented them; that is, they were eager to discover laws by which to explain and predict political and historical facts as though they were as necessary, and thus as reliable, as the physicists once believed natural phenomena to be.

The ultimate aim was neither power nor profit. Nor was it even influence in the world in order to serve particular, tangible interests for the sake of which prestige, an image of the “greatest power in the world,” was needed and purposefully used. The goal was now the image itself, as is manifest in the very language of the problem‐solvers, with their “scenarios” and “audiences,” borrowed from the theater. For this ultimate aim, all policies became short‐term interchangeable means, until finally, when all signs pointed to defeat in the war of attrition, the goal was no longer one of avoiding humiliating defeat but of finding ways and means to avoid admitting it and “save face.”

Image‐making as global policy—not world conquest, but victory in the battle “to win the people's minds"—is indeed something new in the huge arsenal of human follies recorded in history. This was not undertaken by third‐rate nation always apt to boast in order to compensate for the real thing, or by one of the old colonial powers that lost their position as result of World War II and might have been tempted, as de Gaulle was, to bluff their way back to pre‐eminence, but by “the dominant power.”

In the case of the Vietnam war we are confronted With, in addition to falsehoods and confusion, a truly, amazing and entirely honest ignorance of the historically pertinent background: Not only did the decisionmakers seem ignorant of all the wellknown facts of the Chinese revolution and the decade‐old rift between Moscow and Peking that preceded it, but no one at the top knew or considered it important that the Vietnamese had been fighting foreign invaders for almost 2,000 years, or that the notion of Vietnam as a “tiny backward nation” without interest to “civilized” nations, which is, unhappily, often shared by the war critics, stands in flagrant contradiction to the very old and highly developed culture of the region. What Vietnam lacks is not “culture,” but strategic importance, suitable terrain for modern mechanized armies, and rewarding targets for the Air Force. What caused the disastrous defeat of American policies and armed intervention was indeed no quagmire but the willful, deliberate disregard of all facts; historical, political, geographical, for more than twenty‐five years.

The first explanation that comes to mind to answer the question “How could they?” is likely to point to the inter‐connectedness of deception and self‐deception. In the contest between public statements, always overoptimistic, and the truthful reports of the intelligence community, persistently bleak and ominous, the public statements were liable to win simply because they were public. The great advantage of publicly established and accepted propositions over whatever an individual might secretly know or believe to be the truth is neatly illustrated by a medieval anecdote according to which a sentry, on duty. to watch and warn the townspeople of the enemy's approach, jokingly sounded a false alarm—and then was the last to rush to the walls to defend the town against his invented enemies. From this, one may conclude that the more successful a liar is, the more people he has convinced, the more likely it is that he will end by believing his own lies.

In the Pentagon Papers we are confronted with people who did their utmost to win the minds of the people, that is, to manipulate them; but since they labored in a free country, where all kinds of information were available, they never really succeeded. Because of their relatively high station and their position in government, they were better shielded—in spite of their privileged knowledge of “top secrets” —against this public information, which also more or less told the factual truth, than were those whom they tried to convince and of whom they were likely to think in terms of mere audiences, “silent majorities,” who were supposed to watch the scenarists’ productions.

The internal world of government, with its bureaucracy on one hand, its social life on the other, made selfdeception relatively easy. No ivory tower of the scholars has ever better prepared the mind for ignoring the facts of life than did the various think tanks for the problem‐solvers and the reputation of the Whig House for the President's advisers. It was in this atmosphere, where defeat was less feared than admitting defeat, that the misleading statements about the disasters of the Tet offensive and the Cambodian invasion were concocted. But what is even more important is that the truth about such decisive matters could be successfully covered up in these internal circles—but nowhere else—by worries about how to avoid becoming “the first American President to lose a war” and by the always present preoccupations with the next election.

The problem‐solvers, wno lost their minds because they trusted the calculating powers of their brains at the expense of the mind's capacity for experience and its ability to learn from it, were preceded by the ideologists of the cold war period. Anti‐Communism —not the old, often prejudiced hostility of America against Socialism and Communism, so strong in the twenties and still a mainstay of the Republican party during the Roosevelt Administration, but. the postwar comprehensive ideology—was originally the brain child of former’ Communists who needed a new ideology by which to explain and reliably foretell the course of history. This ideology was at the root of all “theories” in Washington since the end of World War II.

This brings us to the root of the matter that, at least partially, might contain the answer to the question, How could they not only start these policies but carry them through to their bitter and absurd end? Defactualization and problem‐solving were welCorned because disregard ‘of reality was inherent in the policies and goals themselves. What did they have to know about Indochina as it really was, when it was no more than a “test case"..or a domino, or a means to “contain China” or prove that we are the mightiest of the superpowers? Or take the case of bombing North Vietnam for the ulterior purpose of building morale in South Vietnam, without much intention of winning a clear‐cut victory and ending the war. How could they be interested in anything as real as victory when they kept the war going not for territorial gain or economic advantage, least of all to help a friend or keep a commitment, and not even for the reality, as distinguished from the image, of power?

When this stage of the game was reached, the initial premise that we shoUld never mind the region or the country itself—inherent in the domino theory—changed into “never mind the enemy.” And this in the midst of war! The result was that the enemy, poor, abused and suffering, grew stronger while “the mightiest country” grew weaker with each passing year.

The aspects of the Pentagon Papers that I have chosen, the aspects of deception, self‐deception, image‐making, ideologizing, and defactualization, are by no means the only features of the papers that deserve to be studied and learned from. There is, for instance, the fact that this massive and systematic effort at self‐examination was commissioned by one of the chief actors, that 36 men could be found to compile the documents and write their. analysis, quite a few of whom “had helped to develop or to carry out the policies they were asked to evaluate,” that one of the authors, when it had become apparent that no one in government was willing to use or even read the results, went to the public and leaked it to the press, and that, finally, the most respectable newspapers in the country dared to bring material that was stamped “top secret” to the widest possible attention.

It has rightly been said by Neil’ Sheehan that Robert McNamara's decision to find out what went wrong, and why, “may turn out to be one of the most important decisions in his seven years at the Pentagon.” It certainly restored, at least for a fleeting moment, this country's reputation in the world. What had happened could indeed hardly have happened anywhere else. It is as though all these people, involved in an unjust war and rightly compromised by it, had suddenly remembered what they owed to their forefathers’ decent respect for the opinions of mankind. cii) 1971, Hannah Arendt’