It’s easy to forget that President Trump’s surprising victory in 2016 depended more on the South than Rust Belt states. Trump won all the former Confederate states except Virginia. Combined, those 10 states provided 155 electoral votes — more than half of his total.

The Republican Party is white and Southern. How did that happen?

Its leaders made a decision to push out blacks. That helped it to dominate Southern politics.

Before the 1970s, Republicans didn’t do nearly so well in the South. With the exception of the short period of Reconstruction after the Civil War, the GOP was notoriously ineffective in the ex-Confederacy. The region was dominated by the Democratic Party from the late 1870s through the second half of the 20th century.

Why the shift? Historians and political scientists traditionally emphasize how the national Democratic Party began supporting civil rights, which alienated white Southern voters. But our research shows that it wasn’t just the Democrats who changed. The Republican Party in the South consciously chose to exclude blacks early in the 20th century, which helped it to dominate Southern politics decades later.

Southern black voters used to support Republicans

Right after the Civil War, black voters were the Republican Party’s main supporters in the South. When formerly enslaved blacks became eligible to vote and run for office, they voted for the party of Lincoln, and GOP state organizations in the South were biracial. Both blacks and whites held leadership positions in the party.

Beginning in the early 1870s, Southern Democrats — in cooperation with terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan — began to restrict black suffrage. They did so first through direct violence and intimidation and, later, by passing legislation to effectively disenfranchise black citizens. As a result, the GOP lost its core constituency.

In a recent article, and in our forthcoming book, “Republican Party Politics and the American South, 1865-1968,” we look at Republican state party organizations in the South before the civil rights era. While the GOP consistently lost Southern elections between the late 1870s and the middle of the 20th century, each Southern state had its own Republican Party organization. These organizations focused not on winning elections, but on participating in national conventions and distributing federal patronage when a Republican held the White House.

Black leaders were gradually pushed out

For a generation after Reconstruction’s end, these Southern state parties had a significant number of black Republicans in leadership positions. In Texas, for example, Norris Wright Cuney — a black man — was the state party “boss” between 1884 and 1896.

But over time, white-supremacist Republicans — known as the Lily-Whites — pushed black leaders like Cuney and their white allies — known as the Black-and-Tans — out of the party.

Although this fight was mostly over control of federal patronage, the Lily-Whites argued that the only way for the GOP to win elections in the region again was to become a “white” party and purge its black leaders. This was because black voters were largely disenfranchised and white Southern voters were unwilling to vote for a “Negro” party.

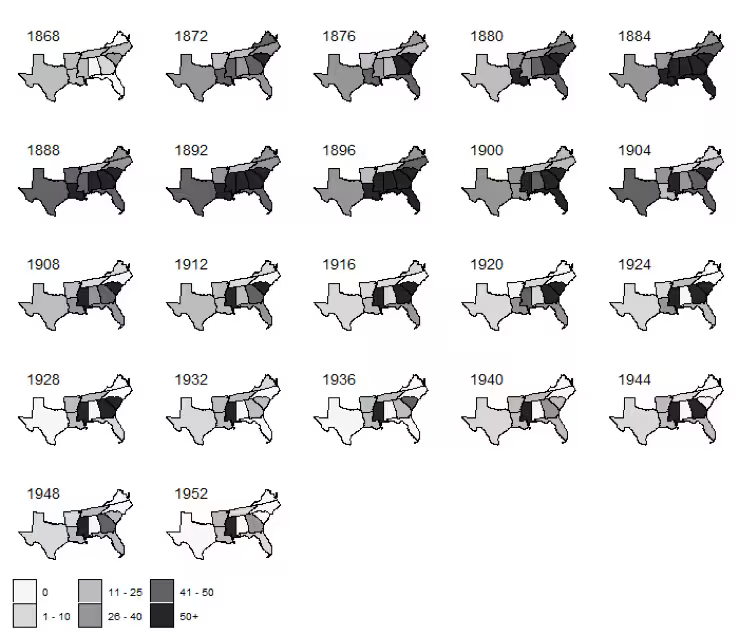

To find out how and when Lily-Whites took control of each Republican state party organization, we collected data on the race of all Southern delegates to Republican National Conventions between 1868 and 1952. Our data shows a common pattern: Most Southern states saw a major decline in black leadership at some point in the early 20th century.

In some states — like North Carolina, Alabama and Virginia — the purge of black leaders was quick and lasting. Other states fended off the Lily-Whites for a time. Mississippi, for example, remained under the control of Perry Howard, a black man, until 1960 — and consistently sent majority black delegations to the GOP convention.

As Republicans pushed out black leaders, they attracted more white voters

Our analysis of the data shows that the Lily-Whites were correct.

During Reconstruction, when black voters were the Republican Party’s core Southern constituency, a whiter party leadership resulted in the GOP losing votes. Black voters were paying attention and punished their state GOP if black leadership declined.

However, after Southern Democrats passed legislation to disenfranchise black voters, that switched. The whiter the party leadership was, the better the GOP did in elections — whether those were presidential, congressional or gubernatorial elections.

This effect was mostly driven by the states of the “Outer South” — Arkansas, Florida, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia. In those states, as the local Republican Party became whiter, its electoral performance improved considerably — although the improvement was not enough for the party to begin winning elections right away.

However, the GOP began its electoral recovery earliest in those Outer-South states. It began winning Southern elections at the presidential level in the 1950s and at the Senate and gubernatorial levels in the 1960s.

Many have noted that whiteness is a fundamental part of today’s Republican Party. Our results suggest that this is nothing new and show where it came from. The Southern GOP consciously decided in the early 20th century to make itself white by excluding blacks from the party leadership. This was a necessary condition for making the Southern Republican Party viable — and ultimately dominant — in elections in the late 20th century.

Boris Heersink (@Boris_Heersink) is an assistant professor of political science at Fordham University and the co-author of “Republican Party Politics and the American South, 1865-1968” (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Jeffery A. Jenkins (@jaj7d) is Provost Professor of Public Policy, Political Science, and Law; Judith & John Bedrosian Chair of Governance and the Public Enterprise; director of the Bedrosian Center; and director of the Political Institutions and Political Economy (PIPE) Collaborative at the Sol Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California. He is co-author most recently of “Republican Party Politics and the American South, 1865-1968” (Cambridge University Press, 2020).