The Red Sea Conflict Is Scrambling Shipping. Europe Is Bearing the Brunt.

Europe is again on the front line of the latest geopolitical tensions, a development that threatens to widen the economic gap between it and the U.S.

By Paul Hannon and William Boston

Jan. 19, 2024 The Wall Street Journal

For the second time in three years, a conflict in Europe’s unruly neighborhood is threatening to weaken an already struggling economy while a more robust U.S. is watching from a safer distance.

This time, attacks by Houthi rebels in Yemen targeting cargo ships in the Red Sea have persuaded more carriers to opt for the safer but longer and more expensive journey around Africa via the Cape of Good Hope.

Those detours are raising freight costs and leading retailers to worry about running out of stock. Some factories have suspended work in the absence of needed parts. Should the threat persist, economists think the decline in inflation Europe enjoyed last year could slow down, pushing back a potential cut in key interest rates.

“This is clearly one of the major downside risks to growth, and upside risks to inflation,” said Ana Boata, chief economist at insurer Allianz Trade. “We could talk about a recessionary risk.”

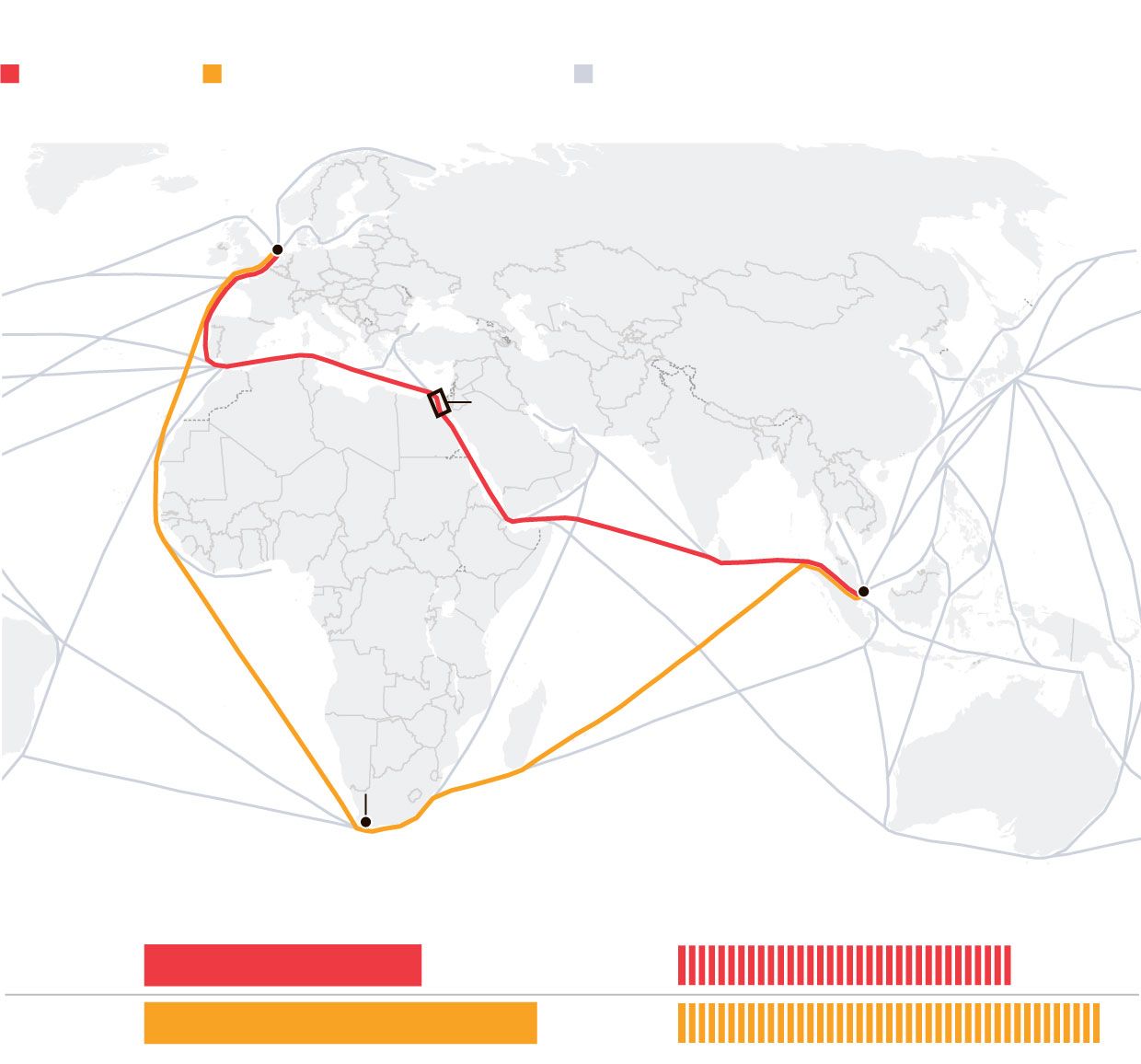

Re-Route

Shipping companies with vessels idling in or near the Suez Canal are considering taking a detour around Africa. The Cape of Good Hope route is considerably longer and burns more fuel, making it less popular than the Suez Canal option.

Ships traveling through the Red Sea carry about 40% of the goods that are traded between Europe and Asia. The Houthis initially claimed to target Israeli ships or those bound for its ports but in practice, their attacks have been indiscriminate. That has prompted more operators to divert their traffic around the Cape of Good Hope.

Last week, Tesla said delays in delivery of components caused by the rerouting of ships would force it to suspend production at its only large factory in Europe, the GigaBerlin plant outside Berlin.

, the Chinese-Swedish automaker, said gearboxes needed to build conventional combustion vehicles at a plant in Belgium were delayed, forcing the company to halt production for three days. , Europe’s largest carmaker by sales, said its plants hadn’t been affected, but that it continued to monitor the situation in close contact with its suppliers. VW said it was rerouting shipments, which was causing some delay.Oxford Economics estimates that a ship traveling at 16.5 knots from Taiwan to the Netherlands via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal takes about 25½ days to complete the journey. But this rises to about 34 days if the journey is diverted around the Cape.

Extra traveling time reduces the annual capacity of each ship, and can have a knock-on effect on freight costs on other routes, including those between Asia and the U.S. According to the Freightos Baltic Index, the average cost of transporting goods in a container across the globe doubled between Dec. 22 and Jan. 12.

Those times could lengthen even further if diverted ships have to wait to take on additional fuel to complete their unplanned journeys at overstretched African ports, of which South Africa’s Durban is the largest.

“We haven’t seen tremendous congestion in Durban,” said Ami Daniel, CEO of shipping consulting firm

.For Europe, the impact of the crisis would largely depend on the extent and duration of the disruption. Economists at Allianz Trade calculate that a doubling of freight costs sustained for more than three months could push the eurozone’s inflation rate up by three-quarters of a percentage point and reduce economic growth by almost a percentage point. With the eurozone’s economy already weakened, that could push it into contraction during 2024.

Paolo Gentiloni, the European Union’s top economic official, told reporters on Monday that the situation in the Red Sea “should be monitored very closely” because it could cause energy prices and inflation to rebound.

There are several reasons why the crisis’s impact on Europe’s economy might be less severe than previous episodes of surging freight costs. For one, businesses have been through a number of supply-chain disruptions over recent years and believe they are better prepared.

“We are affected by the crisis,” said Matthias Zink, CEO of Schaeffler Automotive Technologies. “But it’s under control. Maybe the explanation is that we have a lot of experience now in this resilience or in the reaction to these crises.”

, the French-American-Italian maker of Fiat, Peugeot and Jeep, said it was compensating for delays in rerouted ships “by using some limited airfreight solutions,” adding that the delays had “almost no impact on manufacturing to date.”Patrick Lepperhoff, a consultant with Inverto, a unit of BCG, said past crises had made companies better prepared for sudden shocks. Many companies invested in IT to gain better visibility on their supply chains and got closer to their main suppliers, he added.

In addition to greater preparedness, the economic environment is also different from during the pandemic—a global event affecting supply chains around the world. The current crisis is local, leaving suppliers with more alternatives and many businesses now hold bigger inventories than they did before the pandemic struck. In Europe, weak consumer demand has padded this cushion.

“The Red Sea is not as dangerous to global trade as the events were a few years ago,” said Lepperhoff.

Emily Glazer contributed to this article.

Write to Paul Hannon at paul.hannon@wsj.com and William Boston at william.boston@wsj.com

Copyright ©2024 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Appeared in the January 19, 2024, print edition as 'Red Sea Flare-Up Widens'.