Some things we can never rebuild

28 August 2024

Shojaa al-Safadi’s brother sent him photos of his destroyed library in March 2024. An Israeli attack laid waste to hundreds of volumes and years of collecting.

Courtesy of the family

On the night of 6 October 2023, I was sitting in my home in the Gaza City neighborhood of Tel al-Hawa, engrossed in a book on Greek mythology.

I was reading about the myth of Achilles, a legendary hero whose body was immune to harm from arrows. His only weak point was his heel, which was the reason for his death in battle. Hence the term Achilles’ heel.

I was sitting in my chair in my beloved library, surrounded by the comforting presence of my collection of books. It was a collection started by my father, Omar al-Safadi, an avid collector of rare volumes, encyclopedias and dictionaries.

Following in his footsteps, I devoted myself to gathering hundreds of books across genres, often prioritizing literary treasures over souvenirs during my travels.

The sheer quantity of books I’ve purchased during trips even led customs officers to mistake me for a merchant.

Over the years, I expanded my collection with new acquisitions and eventually was able to dedicate an entire room in my home to my books. Organizing and arranging these books was akin to building my dream home; the library became my personal sanctuary.

The hours I spent immersed in my library were some of the most fulfilling moments of my life, a time when the chaos outside seemed to fade away.

Little did I know that this would be the last peaceful night I would spend in my library.

This time felt different

The following morning, 7 October, Gaza awoke abruptly to the horrors of war.

While conflict is tragically familiar to Palestinians in Gaza, this time felt different. It felt like the end of the world. An evacuation order from the Israeli army forced my family and me to leave our home and neighborhood, with only the bare essentials.

Believing we would return home in a few days, I left my library behind, unaware that I was saying goodbye to an entire life.

My love for books was a legacy from my father. He did not have the opportunity to complete his education. He studied until the sixth grade and then had to leave to work. He was an orphan and education at the time was a luxury.

My father would work in a factory for much of his life, first at the Shomer candy factory in Gaza and then the Polgat factory in Israel. Years later, he worked as a police officer after the Oslo agreement.

But he was passionate about reading and culture. He was determined to acquire and read books from all subjects. He passed away on 20 June 2015 at the age of 74, leaving me his treasured collection.

My books have been my constant companions. Life in Gaza is unstable and precarious, but my books were always present throughout various changes and moves in life, carefully transported and lovingly maintained.

I took meticulous care of each volume, dusting and preserving them with the tenderness one might show a child. Each book in my library held a memory. The worn pages of my father’s favorite poetry collection, the crisp spine of a newly acquired history book – these were more than just objects; they were pieces of my soul.

In my most recent home in Tel al-Hawa, I had finally crafted the library exactly as I had always envisioned it. It wasn’t just a room filled with books; it was an extension of myself.

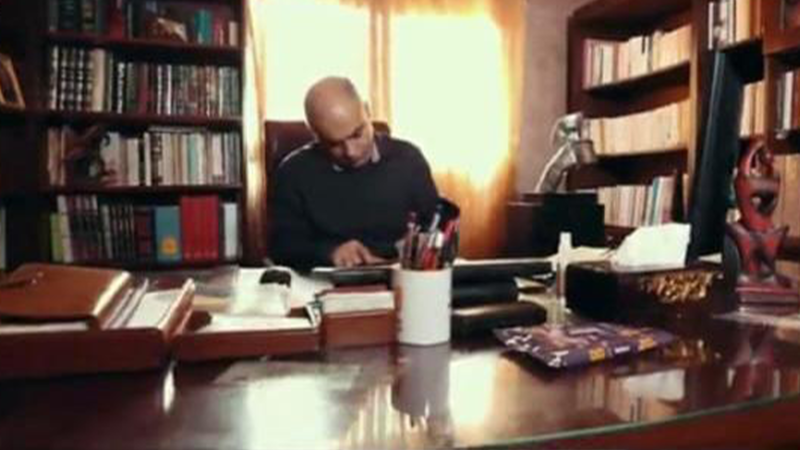

In this screenshot from the Palestine Satellite Channel, Shojaa al-Safadi sits in his library.

Courtesy of the family

A sanctuary reduced to rubble

Months passed. My family and I endured repeated displacements, moving from one temporary shelter to another under deplorable and inhumane conditions. The uncertainty and fear were overwhelming, and information about our home was scarce.

In March 2024, after six agonizing months, my brother, who had remained in northern Gaza, managed to visit our neighborhood. He found a landscape of utter devastation; our home had suffered severe damage from the Israeli attacks.

The photos he sent of my once-pristine library were heartbreaking. My sanctuary had been reduced to rubble, with books scattered, torn and destroyed beyond recognition. The sight brought me to tears, as if I had lost a dear friend or a cherished part of myself.

The library I had inherited from my father and spent a lifetime building was gone.

I felt a profound sense of loss and emptiness. The joy and excitement that my library once brought into my life seemed irretrievable. Israel had not only destroyed physical structures but had also extinguished the passions and dreams housed within them.

Mine was not the only library or repository of knowledge that the Israeli army had attacked in Gaza.

The Israeli army has destroyed many libraries in Gaza, like the Diana Tamari Sabbagh Library, which was targeted in November 2023. This Gaza City library, located at the Rashad al-Shawa Cultural Center, held a special place in my heart, with all the cultural events and poetry symposiums I attended there. Now only memories remain.

Not a single copy survives

Israel’s attacks on various cultural centers seem to be aimed at spreading ignorance in society, striking at the very heart of our cultural identity.

As an author, I’ve lost access to the seven books I wrote. Not a single copy remains. Years of hard work and dedication, destroyed.

My first published book of poems, I Lean on a Stone, is the closest to my heart. It was published by the Palestinian Ministry of Culture, and it was an important step in my literary career.

I wrote these 19 poems with an eye toward ancient myths, interweaving Pharaonic and Greek traditions. I wanted to say that we still live those myths, with their strangeness. They spoke to my sense of alienation, to a desire to escape from the reality in which I live.

Another of my collections that was lost in the destruction of my library is A Homing Pigeon Without a Cooing. This was a collection of short poetic passages. Writing them was an interesting experience, an attempt to use a different poetic method: short telegrams in a poetic language, each with a message from the poet’s spirit.

Also destroyed is my book Wheat Fleeing Toward the Mill. It was a personal text, a storehouse of secrets and experiences documenting years of my life.

Writing is a kind of therapy for me, and each of those books was a slice of my psyche.

The war has killed everything inside us

My wife, our three sons and I are now staying in a small basement in Deir al-Balah. Every day we endure dire circumstances – lack of hygiene, contaminated water and overpriced food. And every other day, when Israel issues its next evacuation orders, I wonder, where do we go next?

Now, after losing everything – our house, the books, my sense of security and even my laptop with years of work and files – we find ourselves moving from one shelter to another, in areas that are continuously bombed.

We cannot settle anywhere. Despite this, I try to read on my phone and write whenever possible; it’s a necessary act to feel alive in the face of overwhelming destruction.

I do not know if my family and I will survive this war, and even if we do, the return of my library – the beautiful wealth of life I had accumulated – seems impossible.

The war has killed everything inside us, leaving us unsure if we will ever rise again.

I grapple with the uncertainty of our survival and the possibility of rebuilding what was lost.

I question whether we can ever truly recover and reclaim the fragments of our former lives.

The war has inflicted unhealable wounds, killing the physical embodiments of our dreams and the spirit within us that dared to hope for peace and normalcy.

Shojaa al-Safadi is a Palestinian writer and poet, a member of the Palestinian Writers Union, and a founder and director of the Friendship Cultural Forum from 2004 to 2014.

Additional articles

Even with all we have lost, Shurouq was special

In every war, there are stories that are told and there are others that are forgotten. Some stories may not even seem so important to an outsider who has yet to experience the complete loss of normalcy and the total absence of any kind of security that war – especially genocidal war – brings. But it is precisely the collapse of all usual standards when you are faced with a daily existential struggle for survival, not just your own, but of everything you hold dear, that also brings out extraordinary courage and love that transcends all boundaries.

Our home was the center of our family life. The family factory – where we make sheets, pillows and blankets from imported fabric – was right next to the house by our orchard, filled with olive, lemon and orange trees. And next to these, my father, Abdul Karim – a lifelong lover of animals – kept a purebred he called Shurouq. In March, an Israeli shell struck the house behind my grandfather’s house. I had never seen my father cry before. Not even during this genocide, with all we had lost: the house, the factory, our shops. Not once. But this time he was crying. He had lost the last thing of his that remained and that reminded him of better times, or normal times. Shurouq was killed in the shelling of the neighbor’s house, which mercifully did not kill anyone else. And I truly understood for the first time what she had meant to him.