https://www.spytalk.co/p/the-searcher

The Searcher

A former State Department officer's journey from Vietnam to investigating CIA drug experiments to private peacemaking efforts

By John Dinges

Sep 14, 2024

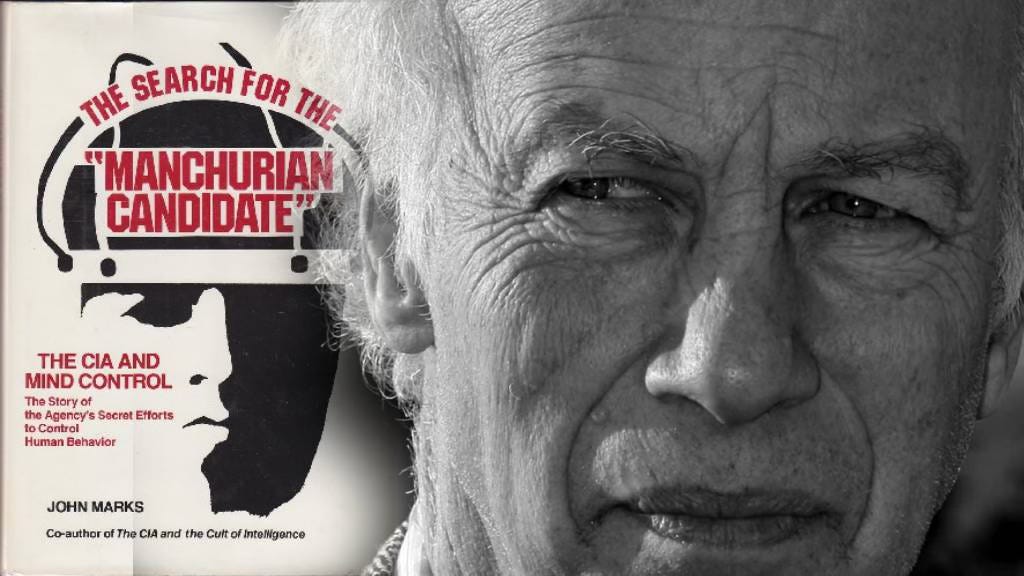

JOHN MARKS DISCOVERED HIS VOCATION AS A PEACEMAKER while writing his 1979 bestseller, The Search for the Manchurian Candidate: The CIA and Mind Control, an exposé of the spy agency’s experiments with psychedelic drugs. He’s been on a very long personal journey since then.

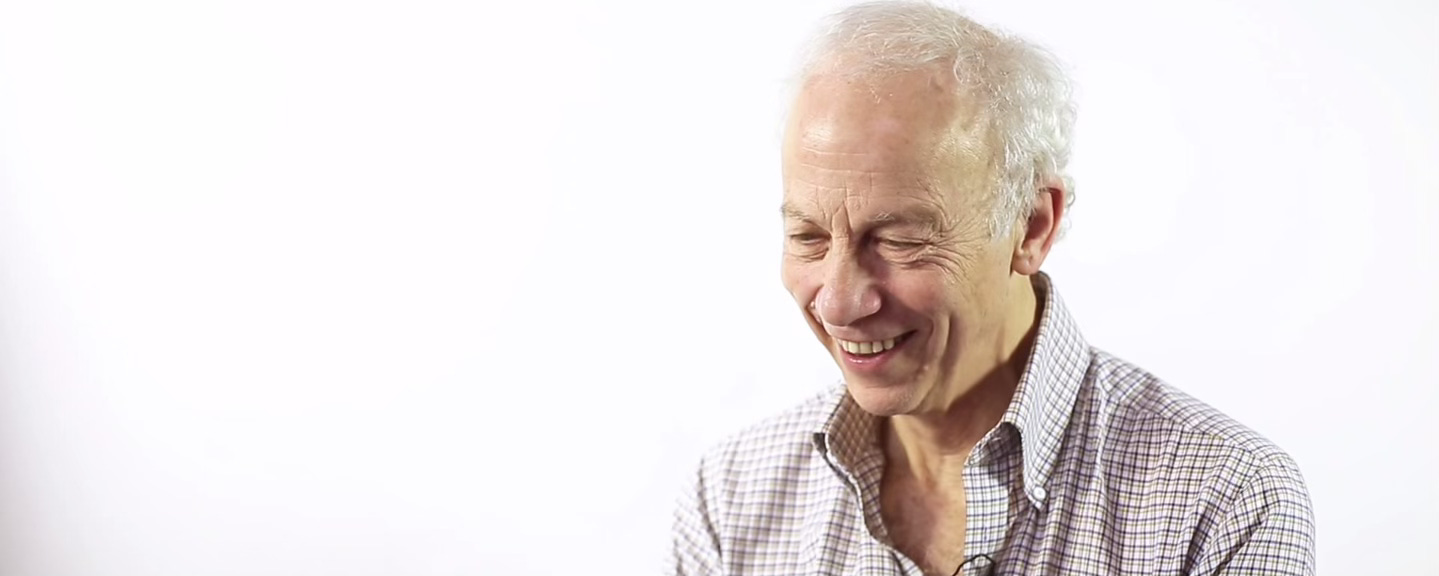

John Marks (Search for Common Ground photo)

Marks was a former State Department foreign service officer who became disillusioned over the Vietnam War and later wrote blockbuster exposés of the CIA. Since then, he has had a distinguished career organizing projects aimed at bringing adversaries together and trying to avert conflict through a nonprofit organization he called Search for Common Ground, which he founded and ran for many years with his partner Susan Collin Marks. Search has a higher profile in Europe than in the United States and has derived much of its funding from the European Union.

In a new book, Marks outlines some of the successes and a few of the failures. He used his familiarity with the dark corners of the intelligence world to leverage his first highly publicized project, which brought together current and former members of the KGB and CIA to pioneer a common effort to prevent international terrorism. While cause and effect cannot be demonstrated, in 1989 the U.S. government and the Soviet Union, still led by reformist Michael Gorbachev, did indeed agree to join forces for a time to combat Islamist terrorism.

Another relative success was the organization’s dogged efforts over a period of 25 years to improve relations between the United States and Iran. The effort began by bringing American wrestlers to a tournament in Tehran—in which the U.S. flag was flown for perhaps the first time since the 1979 hostage crisis. And after some 40 exchanges and meetings, Search’s U.S.-Iran Nuclear Initiatives Group helped pave the way for the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA, the agreement led by the Obama administration to lift sanctions in exchange for Iran’s agreement to put a lid on its nuclear weapons program.

Iran’s chief negotiator, former ambassador to the U.N. Javad Zarif, credited the Group for keeping the negotiations going. “If there is any outcome of the negotiations that is to the satisfaction of both sides, it will be derivative of the discussions of this group,” he said.

Of course, the JCPOA was immensely controversial, fiercely opposed by Israel and its U.S. allies in Congress and ultimately killed when Donald Trump came to power.

Still, there were other accomplishments as Search for Common Ground grew to a high profile nongovernmental organization dealing with some of the world’s thorniest conflicts—among them a series of mostly frustrated initiatives involving Israel and its Arab enemies. Among many Middle East projects, only one seemed to result in some actual common ground, a series of informal meetings to hone proposals for the eventual Israel-Jordan peace treaty that was signed in October 1974.

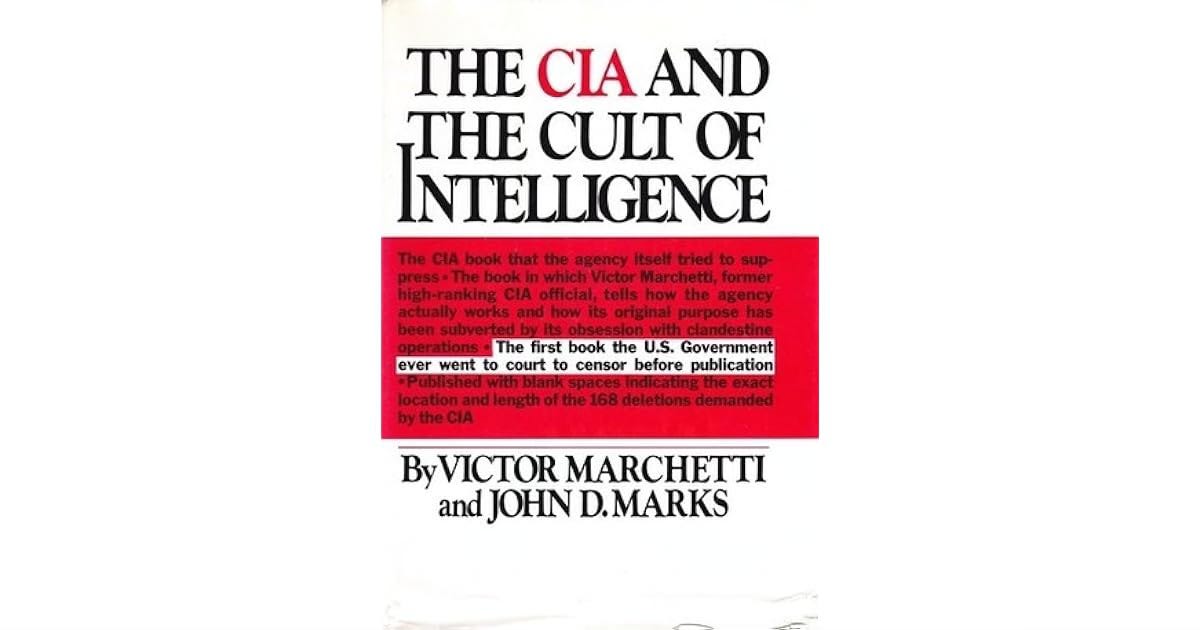

Marks’ book has the somewhat wonky title, From Vision to Action: Remaking the World Through Social Entrepreneurship. OK, that is a very wonky title. Nonetheless, I sensed it was masking a fascinating story, because I had known John Marks for many many years. Before he became an international peacemaker, he was an investigative reporter. He was one of the first and most prominent writers who blew the lid of respectability off the CIA in the early 1970s and exposed it as a bloated wilderness of incompetence and abuse, disguising its failures and illegalities behind a veil of secrecy and impunity. He wrote his first book with CIA whistleblower Victor Marchetti, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence (1974).

Marchetti was a high level CIA insider, an expert on the Soviet military who had served as special assistant to the deputy director of the CIA. He had become increasingly disillusioned as he concluded, with his 360 degree view from near the top, that the agency’s chief job was covert intervention in the affairs of other countries, both friends and foes. He became a heretic determined to debunk what he called the “theology” of national security, which justified overthrowing a democratically elected government in Guatemala, botched the ill-considered invasion of Cuba, and enabled and covered up the U.S. failure in Vietnam.

Marks became his writing partner, first introducing him to the top literary agent David Obst (who also represented Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of Watergate fame) and eventually becoming coauthor after Marchetti floundered for a year with writer’s block. Unlike the relatively deferential portrayals of the CIA in previous books, Marchetti and Marks wrote an in-your-face exposé of the inner workings of the agency, secrecy be damned.

The original idea, according to Marks, was to publish the book’s ample classified revelations without restriction, emulating Daniel Ellsberg’s leak of the Pentagon Papers. But Marchetti, realizing the legal consequences of defying his former employer, got cold feet. The agency first attempted to block the publication entirely with an injunction. Marks wanted to publish “come hell or high water,” but at Marchetti’s insistence—he was a family man with three children—they agreed to submit the text for pre-publication review. A court battle ensued as the CIA tried to gut the book by deleting 339 passages from it, including entire pages. In the end, 168 passages were blacked out, and the book, at Marks’ suggestion, was published with blank spaces, sometimes entire pages, corresponding to the censored passages. The device helped turn the book into a best seller when it came out in 1974.

Living in Washington D.C., Marks became a charter member of a small but exclusive club of national security investigators of the Watergate era, reporters like Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, their editor Larry Stern of the Washington Post, and Seymour Hersh, who had broken the My Lai massacre story and, on joining the New York Times, was also investigating the CIA.

Hersh’s articles later that year, together with the Marks and Marchetti book, are in a direct line of blockbuster revelations about the CIA that in 1975 led to the first serious congressional investigation of CIA abuses, the Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, otherwise known as the Church Committee, for its chairman Senator Frank Church (D-Idaho). Congressional oversight of the CIA began in earnest as a result of the Church investigations and a counterpart in the House headed by Democrat Otis G. Pike of New York

.

Parallel Paths

I got to know Marks a few years later, when he was working on his second book, The Search for the Manchurian Candidate, and I was writing a book on the assassination in Washington D.C. of a Chilean dissident, Orlando Letelier. I used his 1974 article in the Washington Monthly, “How to Spot a Spook,” which showed me how to use publicly available State Department publications to identify CIA agents that had been working covertly in Chile to destabilize—and eventually encourage the overthrow—of the country’s Marxist president, Salvador Allende.

How did John Marks become a muckraker, and then pivot to peacemaker?

A graduate of the elite Phillips Academy and Cornell University, Marks embarked on a traditional upward path as a career officer in the State Department. It was still early in the Vietnam War years. He jokes he was able to avoid the draft because the State Department assigned him to Vietnam, where he worked more than a year in its part of the pacification program, “running around the countryside trying to win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese people,” as he puts it, with civil health and infrastructure programs.

But he learned about another, shadowy wing of pacification, the Phoenix program, initiated by the CIA, which appalled him with its murderous counter-terror teams and brutal Provincial Interrogation Centers. He was not a boat rocker, but the career course ahead was no longer steady.

From there, he got into intelligence work, or as close to it as one can in the State Department. He was made a staff assistant to a legendary senior CIA insider, Ray Cline, whom President Nixon had appointed to run the Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR).

“I used to go to meetings with him where I was, let's say, privy to some of the big secrets,” Marks told me in an interview. “He was a nice man. I mean, he was a fairly hardliner, but he was a nice man. And we had a good relationship. At that point in my life, I wasn't very outspoken. I mean, he knew my views, but I didn't argue with him. I certainly didn't get up at meetings of the U.S. Intelligence Board and say, ‘What you're talking about is a bit out of whack.’”

But getting a glimpse behind the veil of secrecy had started Marks on the road to dissent.

“People used to say then, if only you saw what the president was seeing, you would be in favor of the war in Vietnam,” he said. “I was seeing most of what the president was seeing, and it looked just as bad to me as it did to people who didn't see that stuff.”

Killer Quote

Marks resigned from the State Department in 1970 as a personal protest against the invasion of Cambodia. He got a job on the staff of antiwar Republican Sen. Clifford P. Case of New Jersey. He took with him a single sentence of classified information that he found in the secret minutes of the 40 Committee (the group in charge of vetting and approving CIA covert operations). It was a quote from Henry Kissinger, talking about the covert plans in 1970 to try to prevent Chile’s President-elect Salvador Allende from assuming the office. In it, Kissinger says, “I don’t see why we need to stand by and watch a country go Communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.”

When he saw Kissinger’s statement in the minutes, he said, “I was so horrified I wrote it down on a white piece of paper, a memo pad.”

Leaked eventually to the Washington Post, the statement became one of the most famous quotes showing Kissinger’s disdain for democracy, made as he directed a CIA operation in October 1970 that resulted in the assassination of the head of Chile’s Army.

Many years later, the minutes containing Kissinger's statement were declassified. On the leak, Marks says, “This is the first time I’ve ever admitted it publicly. Don’t get me in trouble.” The declassified account, in fact, attributes the leaked material in articles by Larry Stern in the Washington Post and Seymour Hersh in the New York Times to “the pre-censored manuscript of the Marchetti-Marks book.”

The next step, writing the book with Marchetti, pulled Marks out from under his cloak of anonymity, full of outrage at the war and ready to defy the CIA, even to go to jail, he said, if necessary, to expose its abuses. The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence transformed Marks into a writer and investigative reporter. Its success led to a quick, and lucrative advance to write his next book, which was even a bigger bestseller.

In poring through declassified CIA documents, he had seen a reference to a prisoner in the Korean War who had been taken to Manchuria. He thought of the 1962 movie, The Manchurian Candidate, starring Frank Sinatra, in which a brainwashed Korean War POW returns to the United States programmed to carry out assassinations.

He came up with “The Search for the Manchurian Candidate” as the title for his next book. “It was a good title, and that title got me a big advance, which I got without doing a proposal.”

BBC illustration

Based on 16,000 pages of CIA documents released under the Freedom of Information Act, the book exposed the agency’s pursuit of “mind control” via experiments with hallucinogenic drugs, including on unwitting citizens. It was published to instant acclaim in 1979, and, after almost 50 years in print, it is still churning out $1,000 a year in royalties, he says.

For Marks, Manchurian Candidate was the “intellectual bridge to my new life.” At the height of his success as a writer, he discovered he didn’t like being an investigative reporter. He didn’t like the adversarial side of it, trying to get people to talk to him, having people hang up, confronting people with truths that will damage them publicly. “I mean I know it was good work, but I wasn’t tough enough for it,” he said.

“I also saw that the work I was doing was defined by what I was against. I had no apologies for being against things, but I saw I wanted to build a new system rather than tear down the old system. I didn't want to keep throwing monkey wrenches into the old system. And that became very important to me. I wanted to have a new system.”

“I'm saying this rather glibly,” he added, “but that took me three or four years to figure out what I really wanted to do and to go ahead.”

He discovered he wanted to bring together the hawks and doves, having seen both sides in his work in intelligence and then as a reporter.

Both Sides Now

“I saw that the adversarial approach was not working very well, and I wanted to change the world into a win-win place from a win-lose place. Intellectually, my last book had a real impact on me, you know, the Search for The Manchurian Candidate, because it was a book about how the CIA tried to control the human mind. I saw that you could shift behavior in positive ways, as opposed to what I saw as negative ways.”

He added, “The CIA was, you know, strapping people down on tables and doing strange things to them. I wasn't interested in that at all, but at the other end of the spectrum of behavior change, [I saw it was possible to] kind of mildly move people in different directions.”

The Search for the Manchurian Candidate became the Search for Common Ground. It was kind of a continuation of human interventions but in a benevolent sort of way. It wasn’t a quick and easy process—and stalled by a serious medical crisis. As Marks was thinking through his path from muckraker to peacemaker, he was stricken with a subdural hematoma—bleeding from a vessel in the brain—that put him in a coma for three weeks and almost killed him. It came hard on another personal crisis, a bitter divorce from his first wife.

As he recovered, he formulated the ideas for human change at a global level that became the Search for Common Ground, a nongovernmental diplomatic organization. He was influenced by a stint at the New Age retreat on California’s Big Sur, the Eselan Institute, whose encounter groups delved into Eastern philosophy, mind-body connections and ways to tap human potential. Marks had also been a fellow at Harvard’s Project on Negotiation, based on the conflict resolution methods of Roger Fisher, author of the influential book Getting to Yes.

Launched in 1982, Search struggled early. The 1989 conference bringing together Soviet and American intelligence leaders to combat terrorism was its break-out project. Moreover, its success drew directly on Marks’ roots at the State Department’s INR and his mentor and CIA veteran Ray Cline.

Cline had written his own book, Secrets, Spies and Scholars: Blueprint of the Essential CIA, in 1976, presenting an eloquent defense of the agency in response to a raft of critical books, including that of Marchetti and Marks. Yet Marks was able to enlist Cline as a key player in the CIA-KGB project. Not only Cline, but former CIA director William Colby agreed to participate in a precedent-breaking meeting with active duty and former KGB officers held at a Santa Monica, CA, hotel. About Marks, Colby joked to his KGB counterpart, “I can confirm he was a troublemaker.”

Spook Summit: From left: Igor Beliaev, Political Observer, Literaturnaya Gazeta; Feodor Sherbak, former First Deputy Director, Internal Security Directorate, KGB; William Colby, former Director, CIA; Ray Cline, former Deputy Director, CIA; Natalie Latter, interpreter; John Marks; Valentin Zvezdenkov, former Director of Counterterrorism, KGB; Oleg Proudkov; Foreign Editor, Literaturnaya Gazeta.

By the time Marks resigned as president of Search for Common Ground in 2014, it was backed by major foundations, had several hundred employees and had launched hundreds of projects around the world based on the simple idea of putting adversaries in the same space in open dialogue. He remains as a senior adviser.

He says he conceived his From Vision to Action book as a “practitioner's guide” to what he calls “social entrepreneurship.” Each chapter is built around a series of 10 quirky principles for organizing projects. The chapter on the success of the CIA-KGB meeting demonstrates the value of being a “salami slicer”—an organizer who moves forward one attainable step at a time, relishing small advances rather than pursuing an all-or-nothing strategy.

His guide to promoting Iran-U.S. rapprochement is called “Display Chutzpa”, which is to say, not bad chutzpa, which is arrogance, but good chutzpa, which he describes as being “politely pushy” as a risk taker. Another is “Fingerspitzengefühl,” literally “fingertips feeling,” which has something to do with following your instincts. You get the idea.

Limits to Peace

There were failures, to be sure. Marks relates how Search launched a project on abortion, intending to bring together pro-life and pro-choice advocates. But the predominantly pro-abortion rights community of large funders turned a cold shoulder.

“There’s no sense in the American financial-foundation community that there should be any common ground around abortion,” Marks told me, “‘You’re either with us or against us.’ They think that Israelis and Palestinians or Hutus and Tutsis should find common ground, but not [opposing sides on abortion] at home.”

He says finding common ground is even more difficult in the current climate of fake news, hate speech and political polarization in the United States. He says “memory” of the trajectory of history keeps him optimistic.

“I came up with an idea that history is evolving in positive directions, but unfortunately, it's not a straight line. It's a roller coaster, a sine curve and there are ups and downs. And I see we're in a down period at this point, but I still believe that it's going in positive directions.”

“Look,” he added, “I live in Europe, and the values of the 1960s are alive and well here and have taken root. They haven't in America. The country is split down the middle. [Here], the European Union is one of the greatest exercises in conflict resolution ever. So it's easier to be optimistic sitting where I am in Amsterdam probably than if I were living in Washington, where nobody seems to be optimistic anymore.”

It’s John Marks’ philosophy of hope after a career of searching. ###

John Dinges, a former NPR News managing editor and Godfrey Lowell Cabot Professor of Journalism Emeritus at Columbia University, is author of The Condor Years: How Pinochet and His Allies Brought Terror to Three Continents, and the forthcoming Chile in Their Hearts: The Untold Story of Two Americans Who Went Missing After the Coup.

SpyTalk is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.