Given that the United States removed its theater nuclear capabilities from Asia and the Western Pacific following the Cold War, China today almost certainly enjoys a theater nuclear advantage over the United States. Such expansion will expand as China continues to develop and deploy new warheads capable of being delivered to targets across the Western Pacific from dual-capable missiles.

Additionally, despite maintaining a nominal “No First Use” doctrine when it comes to nuclear employment—as it has maintained since it became a nuclear power—statements by Chinese political and military leaders, as well as nuclear posture changes, suggest that Beijing is reinterpreting what constitutes a nuclear “First Use,” in which case China might feel free to employ nuclear weapons first during a conflict despite its public-facing nuclear employment doctrine.

Although the United States will continue to attempt to use all tools, including diplomacy, to stave off the Chinese nuclear expansion, it should be remembered that the United States has sought for years to reduce the role and salience of nuclear weapons in the global security environment, particularly in Asia. China’s nuclear breakout therefore has far more to do with China’s goals and perceived security interests than it has to do with any American nuclear posture. Thus, any strategy to counter China’s nuclear breakout that relies on the hope that China will reciprocate unilateral U.S. restraint is a strategy that runs counter to history.

Finally, while it is unclear whether China maintains illegal chemical or biological weapons capabilities, it is very possible that it does maintain dual-use chemical or biological programs that could quickly turn into weapons programs as General Anthony Cotton, Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, recently testified. Such a development would be in direct contravention of the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Biological Weapons Convention.

The Threat from Russia. Russia under Vladimir Putin is a secondary but still highly capable adversary, particularly in the nuclear arena. All evidence indicates that while Putin is not seeking to make Russia the preeminent world power, he is opportunistic in his actions as he pursues a long-term goal of the dissolution of NATO as a means to reestablish Russian preeminence in Eastern Europe and beyond.

Over the past 20 years, Russia has invaded Georgia and Ukraine, attempted to annex neighboring territory, committed war crimes, engaged in targeted assassinations against dissidents, used chemical weapons on foreign soil, and regularly threatened the West with nuclear war.

As the war in Ukraine drags on, Russian military forces have taken severe damage, including the loss of hundreds of thousands of soldiers and many frontline tanks and aircraft, and have expended enormous amounts of ammunition, including significant quantities of long-range precision strike capabilities. However, many reports indicate that Russia has reinvested in its own defense industrial base and is producing significant quantities of munitions, intermediate-range precision strike missiles that can range most of Europe, artillery pieces, and even tanks. There also is evidence that Russia’s hypersonic missile capabilities continue to mature and may give Russia the ability to strike a variety of targets with little to no tactical warning.

In addition, given Moscow’s use of chemical weapons in 2018 against Russian dissidents living in the United Kingdom, it is plausible that Russia has some amount of chemical and biological weapons in direct contravention of the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Biological Weapons Convention.

Finally, Russia currently maintains rough strategic parity with the United States in the number of fielded strategic nuclear warheads—1,550 warheads—but has a significant advantage over the United States in the number of non-strategic theater-range nuclear weapons. That is, while the United States has roughly 150 theater non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe, many estimate that Russia fields between 1,500 and 2,200 theater NSNW. Testifying in April 2024, General C.Q. Brown, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, noted “Russia’s focus on expanding and modernizing its nuclear arsenal” and its impact in “further complicat[ing] the global security dynamic.”

The consequence of all this is that Russia presents three specific threats to the West.

- As it rebuilds its conventional capabilities while prosecuting its war in Ukraine, Russia will increasingly present a credible, if localized, conventional military threat on its periphery, including against NATO states that border Russia.

- Russia’s hypersonic and intermediate-range missiles have the potential to inflict limited, episodic damage across a number of targets across Europe.

- Most significantly, Russia’s nuclear advantage presents a grave challenge for the West. This nuclear advantage, coupled with Russia’s struggles to gain significant ground in Ukraine after two years of war, means that Russia has every incentive to rely more heavily on nuclear weapons as a means of coercion and potentially to stave off a conventional battlefield defeat. It could also seek to leverage its nuclear capabilities to coerce or even directly challenge NATO members on its borders.

In short, Russia’s nuclear capabilities, history of invading its neighbors, and attempts at nuclear coercion, along with Putin’s goal of reestablishing Russian dominance in Eastern Europe, make Russia a relatively unpredictable and potentially high-risk threat—a dangerous combination for the state with the world’s largest nuclear arsenal.

The Threat from North Korea. For three decades, North Korea has been a “rogue” state that threatens regional stability. It has a sizable military, albeit one that fields exceedingly old equipment. It does, however, maintain a sizable and increasingly capable ballistic and cruise missile inventory. In addition, North Korea’s nuclear arsenal has expanded slowly but steadily for nearly two decades. It also should not be forgotten that North Korea maintains an active chemical and biological weapons program to supplement its conventional shortcomings.

Over that period, North Korea’s ruling Kim family have threatened the United States, South Korea, and Japan with nuclear strikes. While such threats have been dismissed in years past, the maturation and expansion of North Korea’s missile program and the increasing sophistication of North Korea’s nuclear warheads mean that the United States and its allies cannot dismiss the threat from North Korea. It must be taken as a credible capability that could inflict significant and unacceptable damage on all three nations.

Despite three decades of dialogues, six-party talks, and presidential-level direct engagement, there is zero evidence that North Korea is willing to abandon its nuclear weapons program. In many ways, the Kim family has made it clear that North Korea’s nuclear arsenal is its most important commodity. Given this—and the failure of every American Administration since President Bill Clinton to get North Korea to denuclearize—it is clear that North Korea will remain a nuclear challenge at least until the Kim regime collapses.

Other Potential Nuclear Threats. While the foregoing three nuclear-armed adversaries present threats to the United States and its allies, there are other contingencies and potential adversaries that must be addressed when considering a nuclear posture.

Iran. Iran continues to support a number of malign actors, including the Houthis, Hamas, and Hezbollah, and is the source of much unrest and terrorism in the Middle East. While the Intelligence Community does not assess that Iran has an active nuclear weapons program, Iran’s actions, including the expulsion of International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors, and the discovery of trace particles of highly enriched uranium at Iranian nuclear facilities suggest that Tehran is interested in acquiring nuclear weapons and may not be far from success.

A nuclear-armed Iran is not in America’s national interest, but it is becoming more likely as Iran’s nuclear program continues unimpeded. The United States will therefore continue to pursue diplomatic and multilateral options to prevent Iran from becoming nuclear-armed, but it also maintains the capability and reserves the right to use whatever means it deems necessary to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons.

Terrorists. For a variety of reasons, and despite much fear about the possible emergence of nuclear-armed terrorists, a credible threat of nuclear terrorism has yet to materialize. Nevertheless, the United States will remain vigilant with respect this potential threat and, if and when it does materialize, will use all appropriate means to neutralize terrorists who are actively seeking nuclear weapons.

The Role of America’s Nuclear Deterrent

America’s nuclear deterrent has a number of important functions and is spread across a triad of capabilities, including land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), ballistic missile submarines, and bombers as well as a set of non-strategic nuclear weapons. The totality of America’s strategic triad is being modernized to ensure that America’s deterrent remains credible for the next half-century. Such a modernization, as will be shown below, is necessary but insufficient for the challenges at hand.

The Function of Our Strategic Deterrent. Nuclear weapons are the ultimate guarantor of American security. For decades, both Republican and Democratic Administrations have sought to maintain a robust strategic deterrent as a means to deter strategic attack, assure our allies, achieve U.S. objectives if deterrence fails, and hedge against future uncertainty.

To Deter Strategic Attack. The primary goal of nuclear weapons is to deter a strategic attack on the American homeland, U.S. forces abroad, and allies around the world. Such an attack is most often thought of as a nuclear attack. The American nuclear arsenal therefore is meant to convey to our adversaries that the United States has the will and capability to deter nuclear attack under any conditions and respond to such attacks with the full range of force in the nation’s arsenal.

Strategic attack does not necessarily have to be nuclear, however. Other strategic, non-nuclear attacks could include a biological weapons attack on the American homeland, a significant chemical weapons employment against U.S. forces or citizens, a devastating cyberattack against critical U.S. capabilities, or other forms of strategic attack that take place in space or against space-based targets. While this list is not exhaustive, our adversaries should understand that the types of capabilities used in such an attack are less important than their impact. That is, the United States will respond to any type of attack that has a strategic effect on the American homeland, U.S. citizens, or U.S. interests with overwhelming force.

Such adversaries must know that the United States has both the capability required to carry out a strategic response to a strategic attack and the ability to identify the sources of strategic attacks, that it will hold them accountable for their actions, that attacks below the nuclear threshold can still elicit a U.S. nuclear response, and that any attempt to use nuclear weapons as a means to escalate their way out of a conflict will result in unacceptable consequences for the sources of such attacks.

It is for this reason that the United States will field and maintain a full range of nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities that can respond decisively to strategic attack. The evolving nature of non-nuclear strategic threats, including the growing threat of genetically modified bioweapons, coupled with the need to maintain a credible extended nuclear deterrent, is why every Administration—Republican and Democrat—has refrained from stating either that the United States will never be the first to introduce nuclear weapons on the battlefield or that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons is to deter strategic attack.

To Assure Allies. For decades, the United States has extended nuclear deterrence commitments to our allies in the Indo-Pacific and Europe. Assuring our allies of America’s commitments advances our mutual interests by deterring and, if necessary, defeating adversary aggression before it reaches America’s shores. Assurance is built upon decades of trust, joint force deployments, strategic dialogues, and personnel exchanges. No one—not our own people, our allies, or our adversaries—should doubt the credibility and capability of America’s nuclear umbrella. America’s nuclear arsenal has been its most successful nonproliferation tool in assuring allies that they do not need to pursue their own nuclear weapons programs.

To Achieve U.S. Objectives if Deterrence Fails. No one seeks to employ nuclear weapons, nor would anyone do so lightly. Every U.S. President in the atomic age has considered employing nuclear weapons only in the most extreme circumstances and only for defensive use.

Credibility, however, demands that the United States must maintain a reliable nuclear arsenal that is capable of achieving a variety of effects so that if deterrence fails and America’s adversaries choose to secure their objectives by using violence and force, the United States is able to achieve its objectives.

The United States will not engage in countervalue targeting against civilian population centers, but it reserves the right to employ any tools at its disposal to respond to strategic attack on the United States or its allies. In addition, the United States does not accept a “No First Use” or “Sole Purpose” declaratory policy when it comes to its strategic arsenal.

Any employment of nuclear weapons will adhere to the Law of Armed Conflict and the Uniform Code of Military Justice and will be implemented in a way that is intended to end any conflict at the lowest level of damage possible consistent with the achievement of U.S. objectives. To that end, flexible and limited nuclear employment options require a diverse set of nuclear capabilities, to include land-based, sea-based, and air-launched capabilities of varying yields. Such capabilities should seek to limit the damage our adversaries can inflict by employing credible nuclear systems combined with adaptive planning, effective missile defenses, and robust conventional capabilities. Such non-nuclear capabilities are critically important and can complement the effects provided by nuclear weapons, but they can never replace them.

To Hedge Against Future Uncertainty. The United States has pursued and always will pursue a stable security environment that allows for freedom and prosperity for all of the world’s peoples, but it also must be prepared for a significant degradation in the security environment. Just as the world security environment degraded from 2010 to 2024, it is entirely possible that further degradations will manifest in heretofore unseen ways. Nuclear weapons must therefore remain a credible deterrent against unknown and unknowable developments in the years to come.

As Russia increasingly relies on nuclear coercion as a means of “diplomacy” and as China continues on its path as the world’s fastest-growing nuclear power, the role of nuclear weapons as a hedge against future uncertainty will become more important than ever. This is particularly true during a period when Russia and China have invested so heavily in their defense industrial bases and are seemingly prepared for large-scale, protracted conflict.

In order to hedge, the United States must maintain the ability to produce nuclear warheads and associated delivery mechanisms—to include missiles, bombers, and submarines—at scale rapidly in order to shore up deterrence in times of global uncertainty. This will require sustained investment both in the defense industrial base and across the nuclear enterprise itself.

The Existing Arsenal. In addition to the overall function of America’s strategic deterrent and its non-strategic nuclear weapons, it is important to understand the role of each component within the existing arsenal in order to understand what specific capabilities are required to provide the foregoing functions.

A credible arsenal is one with diverse characteristics that can strike a range of targets, providing a variety of yields, with varying degrees of promptness and different types of trajectories or delivery options to ensure that nothing can prevent our ability to hold at risk the targets the enemy values most and thereby present a credible deterrence posture.

Since the 1950s, the United States has relied on a triad of nuclear systems—ICBMs, bombers, and SSBNs—as the backbone of its strategic deterrent. Each leg of this triad performs specific functions that, while different, are mutually supportive and contribute to a nuclear posture that is meaningful to our allies and adversaries alike. These functions and attributes mean that the nuclear triad is:

- Survivable—Ensures that the force and associated nuclear command and control are resilient and robust enough to survive adversary attack and function throughout the course of a conflict.

- Deployable—Is able to relocate to allied or partner territory for the purposes of political signaling or to enable military effect.

- Diverse—Has a number of range options, yield options, warhead and delivery types, and flight profiles; is able to engage multiple geographic locations despite adversary defenses; and is able to change targets quickly to enable adaptive planning and employment, thus giving the United States the ability to craft effective, credible, tailored deterrent strategies.

- Accurate—Is able to strike targets with precision, thus minimizing the effects on non-targeted areas.

- Penetrating—Is able to overcome adversary active defenses while still holding at risk hardened and deeply buried targets.

- Responsive—Has the ability to deploy and deliver military effects as quickly as possible.

- Visible—Has the ability during crisis and conflict to signal to our allies and our adversaries the political message of America’s willingness to employ nuclear weapons.

ICBMs. The American intercontinental ballistic missile force comprises 400 Minuteman III ICBMs dispersed across a number of states in 450 silos. These missiles are the most responsive and prompt leg of the nuclear triad because of their constant readiness and direct communication with America’s leadership. In addition, given the payload and speed of these weapons, they are difficult for adversary missile defenses to intercept.

Each ICBM is currently loaded with a single, high-yield, highly accurate warhead that can hold targets at risk throughout Europe and Asia in under an hour. Each ICBM also has the capacity to carry additional uploaded nuclear warhead, should there be a policy decision to upload.

In addition, the ability to launch the ICBM force promptly means that our adversaries cannot be sure that they will be able to destroy our ICBMs prior to a launch—meaning that even a large-scale nuclear strike on America’s ICBM force not only could fail to destroy the ICBMs, but also could trigger the large-scale American nuclear response that our adversaries are trying to avoid by targeting our ICBMs in the first place. In this sense, the very existence of the ICBM force contributes both to deterrence and to strategic stability because neither the United States nor an adversary has an incentive to launch a nuclear first strike on the other’s homeland.

Because the ICBMs are stationed in hardened silos, they are highly survivable against all but multiple strikes from high-yield nuclear warheads. The survivability of the ICBM force means that our adversaries cannot destroy a large number of our strategic bombers and ballistic missile submarines as part of an exquisite first strike without also committing significant (and nearly prohibitive) numbers of their high-end forces to the neutralization of America’s missile fields. If the United States were to abandon its ICBM force, our adversaries might be tempted to destroy our bombers and SSBNs while they are in garrison, thereby destroying a large percentage of America’s strategic deterrent with relatively few weapons as part of an exquisite first strike.

America’s Minuteman III force was first deployed in 1970 with an expected service life of roughly 10 years. The last Minuteman was meant to retire during the Reagan Administration; however, for more than 30 years, the United States has been using life extension programs (LEPs) to extend the Minuteman III’s service life. The Sentinel Missile, the Minuteman III’s replacement, is scheduled to come online in the early 2030s.

Bombers. The air leg of America’s deterrent force consists of B-52 and B-2 nuclear-capable bombers. During the first Cold War, America’s strategic bombers were kept on day-to-day strip alert; today’s nuclear-capable bombers are de-alerted but remain ready to respond to crises and deterrence requirements.

Bombers, while not as prompt as the missile force, take hours to reach their target. This longer flight time between the decision to employ nuclear weapons and the time of weapon on target gives policymakers the ability to recall bombers while in flight—a flexibility that is unique among America’s strategic deterrent capabilities.

In addition, because bombers are globally deployable, they provide an important signaling capability. This signaling can be directed both at America’s allies, thus providing a visible assurance of America’s extended deterrence commitment to them, and at America’s adversaries as a visible demonstration of America’s willingness to employ nuclear capabilities in defense of its interests and its allies. The ability to deploy nuclear-capable bombers forward visibly and openly can demonstrate will and ultimately de-escalate tensions in a region by signaling that America is willing to use force and that an adversary may be crossing a red line.

Bombers are also able to carry a variety of munitions, including standoff air-launched cruise missiles, and a variety of gravity bombs with a number of different explosive yields. This flexibility in payload makes bombers of particular utility in the mission as a hedge against uncertainty.

The totality of the bomber leg of the nuclear triad is currently modernizing with the B-61 Mod 11 gravity bombs being replaced by the more advanced-yield B-61 Mod 12 bombs and the high-yield B-83 gravity bombs being replaced by the B-61 Mod 13 bombs. The standoff air-launched cruise missile is being replaced by the Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) cruise missile, and the B-2 stealth bomber will be replaced by the B-21 Raider bomber later this decade. These modernizations of the weapons, missiles, and the bomber itself means that the bomber leg of the triad will be more survivable in a conflict—and therefore more likely to carry out deterrence missions and deliver munitions successfully if deterrence were to fail.

Ballistic Missile Submarines. Ballistic missile submarines equipped with Trident II (D5) submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) are the backbone of America’s strategic deterrent. Taken as a whole, this sea-based leg of America’s triad is the most survivable component of America’s strategic deterrent. Patrolling the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, the SSBNs are virtually undetectable, which means that even if an adversary could carry out a cataclysmic attack on the American homeland, the SSBN force could respond with an assured second-strike capability.

The D5 missiles’ intercontinental range and constant readiness while on patrol enable them to hold targets at risk across Eurasia without interruption. The D5s, which travel at hypersonic speeds, carry a variable loadout of warheads with varying yields, enabling the SSBN force to provide a prompt, responsive, and diverse set of penetrating options against a variety of targets. Despite being undetectable, SSBNs can be highly visible because of their ability to travel to foreign ports and provide visible displays of commitment and presence to signal America’s commitment to a credible deterrent.

Today, the Ohio-class SSBN force, which first entered service in 1981, is in the twilight of its service life. The service life of these vessels, originally intended for 30 years, has been extended to more than 40 years. Further significant life extensions are not feasible beyond the emergency LEPs the Navy is currently considering as a stopgap measure. Beginning in the early 2030s, the Ohio-class submarines will be replaced by the next-generation Columbia-class SSBNs.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons. Since the early days of the first Cold War, the United States has forward deployed low-yield theater-range nuclear weapons to nations on the front lines. Nuclear munitions were stored in Korea, and NATO pilots in Europe were trained to fly their nations’ dual-capable aircraft, which could carry and employ American nuclear weapons. This was called nuclear burden sharing.

Today, NATO allies continue to host American B-61 nuclear gravity bombs as a means to deter regional aggression. NATO allies are transitioning their DCA squadrons from fourth-generation aircraft to fifth-generation F-35 DCA aircraft. Because of their stealthy nature, F-35s will have a greater chance of penetrating enemy air defenses and servicing relevant targets. This upgrade will enhance NATO’s deterrent posture in the face of Russian attempts at nuclear coercion. Therefore, the United States will maintain the ability to forward deploy nuclear-capable bombers and U.S. and allied DCA globally.

In addition, the Department of Defense and Department of Energy will continue two programs established by the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review: the sea-launched cruise missile-nuclear (SLCM-N) and the low-yield SLBM.

The SLCM-N is a major defense acquisition program that is slated for fielding in 2035. It fills a hole in the U.S. arsenal that was created with the retiring of the TLAM-N nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile as directed by the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review. The SLCM-N will be launched from a submarine or surface vessel without having to rely on host nation support. It may have a range of between 1,000 and 2,000 nautical miles, making it an important intermediate-range, penetrating theater capability with a low-yield warhead.

The SLCM-N will serve as a visible or covert assurance to allies in the Indo-Pacific and Europe. Its non-ballistic trajectory, combined with its non-visible generation characteristics, will give our adversaries pause and therefore contribute to America’s ability to deter strategic attacks on our allies. The SLCM-N’s deployability to the Western Pacific or Europe during times of crisis would signal to our adversaries that, despite their theater nuclear advantage, they cannot coerce or gain advantage through nuclear threats or nuclear employment without risking a U.S. theater nuclear response in kind.

Having the ability to counter adversary nuclear aggression with its own theater-range low-yield warhead would also signal to America’s adversaries that Washington has a clear interest in limiting the geographic scope and intensity of a nuclear conflict. In addition, a non-ballistic cruise missile launched from an intermediate range might well obviate the need to overfly third parties—particularly nuclear-armed third parties—in order to hold adversary targets at risk.

Moreover, controlling the weapon’s origin and flight trajectory allows America’s adversaries to discern viable points of origin and therefore could be less likely to invite or legitimize a strike on the American homeland than a nuclear strike that originates from a strategic nuclear system, such as a U.S.-based bomber, an ICBM, or even a strategic ballistic missile submarine, would be. Relatedly, a theater-range weapon launched from an American naval vessel would mitigate the potential of inviting a reprisal not only against the American homeland, but also against allies that might have to host American nuclear weapons that are delivered by aircraft.

In this way, platforms—particularly non-air-launched platforms—that can deliver effects from within a theater of operation reduce the risk of unintended horizontal escalation of a conflict. In other words, increasing the options for delivering nuclear effects, coupled with increasing the above-noted types of nuclear characteristics, gives the United States greater flexibility in signaling and negotiating its willingness to fight a limited nuclear war without necessarily inviting retaliatory strikes on the American homeland. It is almost a certainty that this same logic has informed Russia’s decision to develop its own robust theater nuclear arsenal.

The United States will continue to field the W76-2, the low-yield SLBM introduced following the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review and meant to give the United States a prompt, low-yield nuclear option delivered through a ballistic trajectory, even after SLCM-N is fielded to ensure that America fields a deterrent that is diverse in characteristics and composition.

Importance of the Modernization Program of Record. The United States began its current nuclear modernization program in 2010—when relations with China were mostly positive and before Russia set fire to the global arms control regime, invaded Ukraine, and began its now-tiresome series of nuclear threats against the West—to replace the Cold War legacy triad with new warheads, missiles, bombers, and submarines in a one-for-one manner. Every existing legacy platform or warhead would be replaced by a successor system.

Modestly amended in 2018 to include the low-yield SLBM and the SLCM-N, the 2010 modernization program is a multi-decade endeavor to produce a modernized arsenal. However, the current nuclear modernization program of record is suffering cost overruns and schedule delays in virtually every major aspect of the nuclear enterprise.

The United States has not produced new plutonium pits (the fissile material central to a nuclear detonation) at scale since Rocky Flats ceased production in 1989, and current efforts to restart the capability are years behind schedule. The Los Alamos National Lab will begin to produce plutonium pits at a small scale in late 2024—14 years after the modernization program began—and the Savannah River site’s ability to produce plutonium pits in any meaningful quantity is approximately a decade away. Other key projects, such as the Uranium Processing Facility and Lithium Processing Facility, are similarly over budget and behind schedule.

After not having built nuclear weapons or produced nuclear fissile material in almost three and a half decades, the United States is having to relearn how to enrich uranium for defense purposes. Despite some attempts by the government to shelve critical projects, such as the Tritium Finishing Facility in South Carolina and the High Explosive Synthesis, Formulation, and Production (HESFP) Facility in Texas, the modernization program of record must be not only sustained, but accelerated and expanded.

The Minuteman III ICBM was designed to retire in the 1980s. Its replacement, the Sentinel missile, will replace it beginning in the early 2030s—50 years after Minuteman III was meant to exit service. The Ohio-class SSBNs were designed for a 30-year life span. Those life spans will be extended to 42 years. The B-52 first flew in the 1950s as a nuclear-capable bomber and almost assuredly will do so for another 20 years. The B-2 stealth bomber, which first flew at the end of the Cold War, will be replaced later this decade by the next-generation B-21 bomber, which will be capable of performing nuclear and non-nuclear missions.

The Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) is expected to build the first new nuclear warhead in roughly three and a half decades—the W-93—later this year. Meanwhile, most nuclear warheads in the arsenal are older than the median age of the average American. While it is safe to assume that the current force of bombers, submarines, missiles, and associated warheads will continue to perform their military function until they are replaced with the new arsenal in the coming decade, our nation cannot accept further delays in the modernization of its strategic deterrent.

In many cases, this investment in America’s strategic deterrent will pay dividends for the next half-century, including the 2070s and 2080s when the new warheads, ballistic missile submarines, and many of the missiles are expected to be retired. This twice-in-a-century moment of recapitalizing our nuclear enterprise and ensuring that the cornerstone of American security remains strong is of paramount importance in protecting our nation.

If the United States is unable to field a credible nuclear deterrent by the 2030s, when China likely will reach parity with the United States and the current U.S. ICBM and submarine force will age out, America’s enemies could well become even more emboldened than they are now and believe that during an acute crisis they can escalate to the nuclear threshold while facing a hobbled and undersized American nuclear deterrent.

The Need to Revitalize the U.S. Arsenal for the 21st Century

The nuclear threats posed by China, Russia, and North Korea are growing, further degrading the global security environment. At the same time, America’s current nuclear modernization program of record—long-overdue though it is—is over budget, is behind schedule, and was designed to provide effective deterrence for a world that was far more benign than the one we see today. That program of record, as the 2023 Strategic Posture Commission noted, is “necessary but not sufficient” to deter America’s adversaries in a period of growing global instability. Accordingly, America must invest in a larger and more diverse strategic arsenal.

Current Program of Record “Necessary but Not Sufficient” for the Next Half-Century. As noted, the nuclear modernization program of record that includes submarines, bombers, missiles, and warheads was established in 2010 when the security environment was relatively benign and stable—but it is worth remembering just how stable the 2010 environment was in comparison with the environment of the mid-2020s.

The 2010 New START nuclear arms treaty between the United States and Russia was seen in many quarters as the beginning of a new era of arms control. At the signing of New START, President Obama remarked, “Going forward, we hope to pursue discussions with Russia on reducing both our strategic and tactical weapons, including nondeployed weapons.”

In addition to deeper cuts in the Russian and American nuclear strategic and non-strategic arsenals (also known as tactical nuclear weapons), national security professionals anticipated future multilateral arms control treaties that might include China and other nuclear powers. The assumption was that modernization would ensure that the strategic arsenal remained adequate to deal with a relatively benign security environment. This point was made explicitly by General Kevin Chilton, then Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, when asked by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee whether the smaller but modernized arsenal provided for in New START was more than what was needed for the 2010 threat environment: “I think the arsenal that we have is exactly what is needed today to provide the deterrent.”

Following New START, many hoped that additional nuclear arms control treaties would reduce total arsenals worldwide, eventually culminating in a world without nuclear weapons. In awarding him the Nobel Peace Prize, the Nobel Committee cited President Obama’s efforts toward global “nuclear disarmament” as a major reason for his selection.

The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review identified “nuclear terrorism” as the largest threat to American security and noted that “[t]he United States and China are increasingly interdependent and their shared responsibilities for addressing global security threats, such as weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferation and terrorism, are growing.” In one of the few passages that dealt with both China and Russia, the NPR stated that “[by] promoting strategic stability with Russia and China and improving transparency and mutual confidence, we can help create the conditions for moving toward a world without nuclear weapons….”

Upon these assumptions, now revealed to be seriously flawed no matter how well-intentioned they were at the time, the current American nuclear modernization program was built.

The New START nuclear arms treaty limited both Russia and the United States to strategic nuclear weapons and was meant to be a waypoint or stopgap measure on the path to a broader, multilateral nuclear reduction treaty that would lower both the strategic and non-strategic nuclear arsenals in Russia and the United States. However, Russia has rejected repeated attempts to engage in a follow-on treaty, and China has rejected both preliminary inquiries for nuclear arms treaties and meaningful attempts to engage in broader strategic dialogues on issues related to stability, risk reduction, or confidence-building measures. Moreover, Russia retains a non-strategic nuclear arsenal that is roughly 2,000 warheads larger than that of the United States, and China is the world’s fastest-growing nuclear power and is on track to reach parity with the United States by the mid-2030s.

Add to these developments Russia’s attempts at nuclear coercion and China’s investment in dual-capable theater systems, and it is clear that the benign security environment foreseen in 2010—the one in which the United States decided it needed 1,550 strategic nuclear weapons arrayed on B-21 bombers, Columbia-class SSBNs, and Sentinel missiles to maintain strategic stability and a credible deterrent posture—never materialized.

If the 2010 nuclear modernization program of record was sufficient to ensure strategic stability in a benign security environment, it is fair to question whether or not it is still sufficient for the degrading security environment of the 2020s or the security environment that may exist in the 2030s and 2040s.

It is also fair to say that the United States should take steps to build and field a strategic deterrent—one that incorporates nuclear and conventional capabilities along with active and passive defenses—that is credible for the security environment of the next half-century. This is not to say that the United States need field a nuclear arsenal that is as large as those of Russia and China combined, but it does need to field an arsenal that is sufficiently credible to deter our adversaries from conducting strategic attacks on or significant aggression against the United States or its key allies. Such an arsenal likely should be modestly larger and more diverse than the one we have today at the strategic level but significantly larger and far more diverse than the non-strategic arsenal that we have today.

In light of all this, the 2023 congressionally mandated Strategic Posture Commission noted that the 2010 nuclear program of record was “necessary but insufficient” and that a new posture was needed. To prepare for the emerging threat environment and ensure that the United States is able to field a credible deterrent that deters strategic attack, the United States must therefore build a new arsenal for the 21st century.

Consequences of Not Building the Arsenal for the 21st Century. If the functions of nuclear weapons are to deter strategic attack, assure allies, achieve U.S. objectives if deterrence fails, and hedge against future uncertainty, any review of nuclear posture must consider the consequences of failure: What are the consequences if America’s strategic deterrent does not perform its functions? What might that look like in practice?

- Failure to Deter Strategic Attack. An arsenal that is not sufficient to meet deterrence requirements relevant to a variety of adversaries could lead to the first use of nuclear weapons in war since 1945, the consequences of which would be horrendous, by adversaries who believe that they had such a degree of nuclear advantage that they could employ nuclear weapons without fear of the consequences. Put another way, failure to field a credible deterrent could incentivize our adversaries to conduct strategic attacks—whether they took the form of nuclear attacks, strategic cyberattacks, or bioattacks—on the United States and its allies.

- Failure to Assure Allies. An arsenal that is not sufficient to meet extended deterrence and assurance requirements could lead to proliferation in some of the most volatile parts of the world, potentially unraveling alliances that took decades to build. While selective allied proliferation may be an acceptable alternative to nuclear war, it is a sub-optimal development and should be avoided if possible. A credible arsenal that deters our adversaries and assures our allies is therefore one of the strongest nonproliferation tools available to the United States.

- Failure to Achieve Objectives if Deterrence Fails. An arsenal that is not sufficient to achieve warfighting objectives if deterrence fails could lead to an increased chance of losing a conflict and at greater cost than would be the case with a credible deterrent. Put another way, if the American nuclear arsenal could not achieve battlefield objectives if an adversary was not deterred from carrying out a strategic attack on the United States or its allies, the United States and its allies could very possibly find themselves in a large-scale, industrialized conflict with far more casualties than would the case if nuclear weapons were used to end a conflict rapidly and decisively.

- Failure to Hedge Against Future Uncertainty. Failure to keep production lines operating for bombers, missiles, submarines, and warheads and a decision that more or more diverse strategic capabilities are needed as a hedge against new security threats could lead to crash nuclear programs as a means to offset or catch up with America’s adversaries. Such programs would almost certainly end up being more expensive than sustained investments in America’s nuclear enterprise and less likely to meet the needs of policy and strategy.

Credible Deterrence: More Than Nuclear Weapons. Credible deterrence requires more than nuclear weapons. It requires conventional forces, such as long-range precision fires, ground forces, fighter aircraft, naval surface combatants, sealift, airlift, drones, air refueling tankers, and a range of active and passive defenses that include integrated air and missile defenses as well as a distributed and resilient force posture.

Cyber networks, command and control, surveillance and reconnaissance architectures, and space-based sensors and the workforce that enables them are critical components of a credible deterrence posture. New technologies that leverage artificial intelligence and machine learning may also prove to be powerful contributors to deterrence.

This does not mean, however, that such non-nuclear capabilities are sufficient for a credible deterrent posture. Nuclear weapons—and their destructive power—are essential if the United States is to maintain a credible strategic deterrent.

Toward a Larger, More Diverse Strategic Arsenal. To prepare for the emerging security environment, the United States must field a credible strategic deterrent that is moderately larger and somewhat more diverse than the current arsenal. To that end, the United States will seek to field the following force by 2035.

Strategic Bombers. The United States will continue to field a mix of B-52 and B-21 nuclear-capable bombers into the 2030s. At least 100 of the B-21s will be nuclear-capable.

Within the strategic arsenal, the United States will field 200 B-61 gravity bombs of various configurations. It will also field a stockpile of 1,000 LRSO nuclear cruise missiles.

ICBMs. The United States will field of an arsenal of 450 Sentinel ICBMs, 400 of which will be silo-based. Each missile will carry a mix of one to three warheads of various yields.

The United States will also field a road-mobile variant of the Sentinel missile to ensure that it has an additional second-strike capability throughout the program life of the Columbia-class SSBN fleet. The Columbia-class boats have an expected life span of roughly 40 years, which means that they will be operating into the early 2080s.

It is assumed that the Columbia-class boats, built using 2020s technology, will remain undetectable throughout most of the 21st century; that U.S. adversaries will not develop new technologies with which they can detect the submarines; and that the U.S. will therefore retain an assured second-strike capability that will disincentivize U.S. adversaries from attempting a first strike.

However, these assumptions raise critical issues. It is not certain that the Columbia-class submarines will be undetectable a half-century from now. Nor is it certain that the technologies and capabilities developed in the 2020s will not be overcome by heretofore undeveloped detection technologies.

Because it is not certain that 2020s technology will be undetectable through the 2080s, it is in the U.S. interest to consider an additional survivable, second-strike capability as a hedge against the day when the SSBNs may no longer be undetectable. The United States will therefore field a small road-mobile Sentinel force as a hedge against an advancement in anti-submarine warfare by our adversaries. The Air Force will design and field vertical erector launchers that can be attached to heavy trucks that are capable of holding and launching either the Sentinel ICBM or modified Sentinel ICBMs as may be required. Combined with security details on accompanying vehicles, the Sentinel becomes a road-mobile ICBM—something that it is, while not impossible, exceedingly difficult to target.

Road-mobile Sentinels will be permanently stationed in garrisons on existing missile bases but will exit those garrisons and move on randomized circuits during exercises or times of crisis as a signaling tool. Air Force missileers will operate and drive them on designated public and Defense Department roads and highways. Road-mobile Sentinels will be armed with up to three nuclear warheads of variable yield, giving them the equivalent of the striking power of a submarine-launched ballistic missile.

Road-mobile Sentinels will operate inside American territory along preapproved (but not preplanned) routes in relatively unpopulated areas, thus—given the flight times that even extremely fast missiles need to traverse from Russia or China to the United States—creating significant targeting challenges for our adversaries. Should a launch against the American homeland be detected, the ICBMs will be able to move to any number of launch sites to await further orders (to include launch or alert orders).

In this way, road-mobile Sentinels will provide the United States with a backup second-strike capability for most of the rest of the 21st century.

Columbia-Class SSBNs. First fielded in the 1960s, nuclear ballistic missile submarines patrol the waters of the North Atlantic and Pacific oceans undetected with only the ships’ captains knowing exactly where they lie. The value of these submarines lies in their secrecy and their ability to deliver scores of nuclear warheads in a relatively brief period of time. Amazingly silent to the point of being undetectable, they represent the assured second-strike leg of the American nuclear triad.

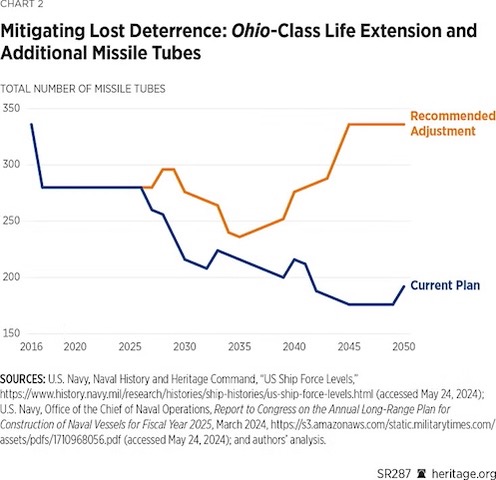

The Columbia-class SSBNs will perform a function similar to that of the Ohio-class boats, albeit in a smaller quantity. The current program of record calls for the United States to replace the 14 Ohio-class SSBNs with 12 Columbia-class boats at the rate of one boat per year beginning in 2031. Although the Navy will field a smaller fleet, the current program of record calls for the Columbia-class boats to carry fewer missiles than the current Ohio-class SSBNs carry.

When originally deployed, the Ohio class operated 24 ballistic missile tubes. After the 2010 New START nuclear arms control treaty entered into force, the U.S. Navy shuttered four ballistic missile tubes to comply with the treaty. The Columbia class is currently programmed to have a smaller missile capacity, fielding only 16 missile tubes per boat.

With the current Trident II (D5) missile, this fleet of 12 Columbia SSBNs could deploy a maximum of 1,920 warheads versus the nearly 5,000 possible warheads loaded onto the original Ohio-class ballistic missile fleet. The new Columbia SSBNs are designed to be the quietest ever built and therefore safely undetectable by current technologies. Averaging between $8.4 billion and $9.2 billion per boat for the 12 to be built, they are admittedly expensive, but they will be patrolling the world’s oceans and providing a continuous deterrence presence into the 2080s.

Given the increasing number and diversity of adversary nuclear weapons, which create additional targets that the United States must consider holding at risk to deter strategic attack on the United States or its allies and to hedge against future uncertainty and further degradations in the security environment, it is incumbent upon the United States to field a larger SSBN force for the next half-century to ensure that it is capable of fielding a credible deterrent.

The fundamental question facing the U.S. Navy is how the current ballistic missile submarine program of record, conceptualized in 2010, can be amended to ensure that we have a fleet of ballistic missile submarines that is sufficient to maintain a credible deterrent into the 2080s.

The U.S. Navy has a duty to ensure the viability and credibility of the nation’s assured second-strike capability in a way that is flexible and responsive to the evolving threat environment. For this reason, it is time to revisit America’s at-sea deterrent writ large. To this end, the United States will take immediate action on the existing Ohio-class SSBN fleet and longer-term actions on the Columbia-class fleet.

Beginning in February 2026, the Navy will reopen the missile tubes that were shuttered on Ohio-class SSBNs as a result of the New START treaty limitations, thus bringing the total number of tubes to 24 on each Ohio-class submarine. Each Ohio will carry the full complement of D5 Trident SLBMs akin to their pre–New START loadout.

In addition, the Navy will amend the Columbia program of record as follows.

Columbia-class boats from hulls seven onwards will carry two additional quad packs (the modular components that carry four ballistic missile tubes per component) per boat, bringing the total number of tubes per boat to 24. Eight additional missile tubes on future Columbia boats will enable each SSBN to carry upwards of 40 more nuclear warheads, allowing each boat to hold more targets at risk and strengthening the United States’ deterrent credibility.

This NPR recognizes the risks associated with amending the nuclear modernization program of record in the immediate term. It is for this reason that such a redesign will be effective beginning with the seventh Columbia, delivery of which is expected in 2036. This maximum addition of missile tubes from the seventh through 12th boats, for a total in 2042 of 240 missile tubes versus the currently planned 192 when the last planned Columbia is delivered, will provide the United States with a hedge against strategic risk by ensuring that the United States will not have capacity shortfalls if the U.S. nuclear arsenal of the coming decades must be increased to a level significantly higher than that of the 2030s.

Next, the Navy will expand the Columbia program of record to include four additional SSBNs and will make the necessary budgetary and industrial plans for such an expansion. This programmatic expansion is necessary not only to hedge against an uncertain 21st century future and maintain a credible deterrence posture against a single nuclear peer—the driving construct that led the U.S. Navy to program for 12 Columbia SSBNs in 2010—but also to deter two nuclear peers in the 2030s.

Assuming that the build rate achieved by 2031 of one Columbia a year is sustained, the United States will build a total of 16 SSBNs by 2045. In addition, the seventh through 16th Columbia boats will be built with 24 missile tubes each. This will give the Columbia class a total of 336 more ballistic missile tubes than the 192 currently programmed.

In addition, the Navy will continue its expansion of dry docks and shipyards, along with bases, to accommodate the larger Columbia-class submarines.