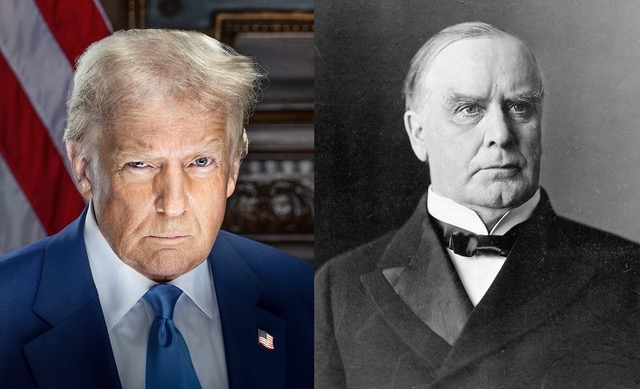

Why Does Trump Like William McKinley So Much?

It was something of an irony that Donald Trump chose to extol William McKinley in his inaugural speech last week, passing over McKinley’s immediate predecessor Grover Cleveland, who for 128 years had been the only president in history to serve two non-consecutive terms — until Trump.

In his first spate of Executive Orders, signed upon taking office January 20, Trump hailed McKinley as having “heroically led our Nation to victory in the Spanish-American War. Under his leadership, the United States enjoyed rapid economic growth and prosperity, including an expansion of territorial gains for the Nation.” One of these “territorial gains” was the Philippines, whose war of colonial conquest McKinley inherited from the battered Spanish Empire. The Philippine-American war was highly controversial at the time, becoming the first instance in US history when masses of US soldiers were deployed to fight across distant oceans — in a country that McKinley himself admitted he would barely be able to locate on a map.

It’s still not very well understood or established why McKinley chose to conquer the Philippines — thereby repudiating over a century of US foreign policy which, at least until that point, was essentially confined to America’s immediate continental ambitions. McKinley claimed that when contemplating the momentous matter, he would fall to his knees and beg for divine guidance. “One night late, it came to me this way,” McKinley wrote. “There was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos and uplift them and Christianize them, and by God’s grace do the very best we could for them, as our fellow men for whom Christ also died.”

McKinley’s unfamiliarity with the Philippines also evidently extended to his lack of knowledge that Filipinos were already predominantly Catholic, and therefore would need to be “Christianized” only in the sense that “Christianization” meant the imposition of American military governance. The war itself was brutal. As Stephen Kinzer, the journalist and historian, wrote: “When two companies under the command of General Lloyd Wheaton were ambushed southeast of Manila, Wheaton ordered every town and village within twelve miles to be destroyed and their inhabitants killed.” For excellent overviews of the Spanish-American War and related endeavors, I recommend Kinzer’s Overthrow (2006) and The True Flag (2017), both of which provide much of the source material for my own understanding of this period.

Grover Cleveland, having completed his two non-consecutive terms, became a strenuous opponent of McKinley’s foreign policy, joining the newly created “American Anti-Imperialist League” as one of its most high-profile members, along with figures like Mark Twain and Andrew Carnegie. Cleveland had already been chagrined at his inability to pump the brakes on the regime change annexation of Hawaii, remarking: “I regarded, and still regard, the proposed annexation of those islands as not only opposed to our national policy, but as a perversion of our national mission.” Upon leaving his second (non-consecutive) term, Cleveland soon set out to campaign against what he called the “schemes of imperialism” that were proliferating as a primary aim of US statecraft, first as to Hawaii, and then subsequently Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines.

The term “anti-imperialist,” though later suffused with extraneous ideological jargon, had a very specific meaning in that era, describing “a person who opposed the acquisition of a colonial empire in the wake of the Spanish-American War.” Notable Americans like Cleveland, Twain, and Carnegie were aghast that the US was taking on the characteristics of reviled European empires, which they saw as in fundamental conflict with America’s founding ethos.

The original manifesto of the League declares:

Whether the ruthless slaughter of the Filipinos shall end next month or next year is but an incident in a contest that must go on until the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States are rescued from the hands of their betrayers. Those who dispute about standards of value while the foundation of the Republic is undermined will be listened to as little as those who would wrangle about the small economies of the household while the house is on fire. The training of a great people for a century, the aspiration for liberty of a vast immigration are forces that will hurl aside those who in the delirium of conquest seek to destroy the character of our institutions.

We deny that the obligation of all citizens to support their Government in times of grave National peril applies to the present situation. If an Administration may with impunity ignore the issues upon which it was chosen, deliberately create a condition of war anywhere on the face of the globe, debauch the civil service for spoils to promote the adventure, organize a truth suppressing censorship and demand of all citizens a suspension of judgment and their unanimous support while it chooses to continue the fighting, representative government itself is imperiled.

It was McKinley who infamously ordered the battleship Maine to Havana harbor, ostensibly on what was to have been a “friendly visit,” as war fever began to brew. The ship was sunk under circumstances that are still in question, but the initial certainty with which it was declared an ‘unprovoked’ Spanish attack — the narrative propounded by pro-war propaganda newspapers — was certainly bunk. US military intervention in Cuba was presented as the selfless empowerment of rebels to cast off European colonial subjugation; McKinley rebuffed repeated offers from the Spanish prime minister to resolve the conflict diplomatically. “A spirit of wild jingoism seems to have taken possession of this usually conservative body,” McKinley’s personal secretary wrote in his diary, with satisfaction, when Congress approved McKinley’s request to formally declare war on Spain. Contrary to prior assurances that the US would not be in the business of conquering Cuba once the Spanish were expelled, McKinley proceeded to place the island under US military rule. As it turned out, McKinley had decided the US would in fact seize the island by “the law of belligerent right over conquered territory.” The original impetus for the war, much more modest in scope and altruistic-sounding in purpose, was quickly scrapped.

It seems unlikely that Donald Trump himself is especially well-versed in the presidency of William McKinley. But his speechwriting and policymaking operation apparently saw fit to channel McKinley in his very first acts as a second term president — notably glossing over another potential analog in Cleveland. So for whatever reason, Trump has chosen to align his present designs with the historical record of the McKinley-era imperialists. This could have multiple interpretations, ranging from ominous to innocuous. However, if one looks at Trump’s rhetoric around the potential annexation of Greenland, he’s taken to framing it as “for the protection of the free world” — the type of hoary platitude that has long overlain imperial lust. It frankly sounds like something Trump would never say off the cuff, and more evokes the prepared remarks of George W. Bush, or, for that matter, Joe Biden. Trump insists that only the US can “provide freedom” to Greenland, and defense against Russia and China.

This gets to a fallacy sometimes evinced by a particularly confused segment of Trump supporters and opponents, where they seem to jointly believe that Trump somehow opposes or seeks to curtail the US-led hegemonic order. McKinley would be an odd model to cite if Trump’s objective was harmonious relations among rival states and a cessation of warfare — or a rollback of American imperium.

In his day-one Executive Order, Trump declared that Mount McKinley would be reinstated as the official name of the mountain “Denali” in Alaska. While the revocation of the indigenous Alaskan name was vaguely presented as another triumph for purging “woke” excess from the government, the majority of the Alaskan political class has long been in favor of “Denali.” This includes Republicans like both sitting US Senators, as well as the late Don Young, the Republican Congressman who served 49 years as Alaska’s sole representative in the House. His recently elected Republican successor Nick Begich addressed the matter by simply saying, “What people in the lower 48 call Denali is not of my concern.” The Alaska state legislature then passed a resolution asking Trump to reconsider the order. “Mount McKinley” has more tended to be a pet project of Ohio legislators who enjoy the idea of their native-son’s name adorning a large mountain, rather than anything that falls along a hackneyed woke/anti-woke divide.

It’s true enough that the name of a mountain in Alaska is probably not of profound significance in the grand scheme of things, but Trump and his cadre have nonetheless chosen to send a certain signal of policy intent that could presumably go far beyond the Interior Department’s naming protocols. Otherwise, it would be odd to just randomly make a historical detour embracing the legacy of William McKinley — the president who turned America into a globe-spanning empire.

If you missed any of my inauguration video coverage last week, you can view it here, here, and here. One of the most genuinely disturbing interviews I’ve ever done, with former Rep. Cori Bush (D-MO), is here.