https://www.telegraph.co.uk/gift/a4e72067493199ef

China will soon once again be the primary civilisation of the world

The Middle Kingdom is on its way back to its former pre-eminence

15 June 2025

In May I had the opportunity to spend a month travelling around China. Many things caught my attention while I was there. In general, I came away with some strong and clear impressions, from what I observed, from interactions with people there and from things guides and others said.

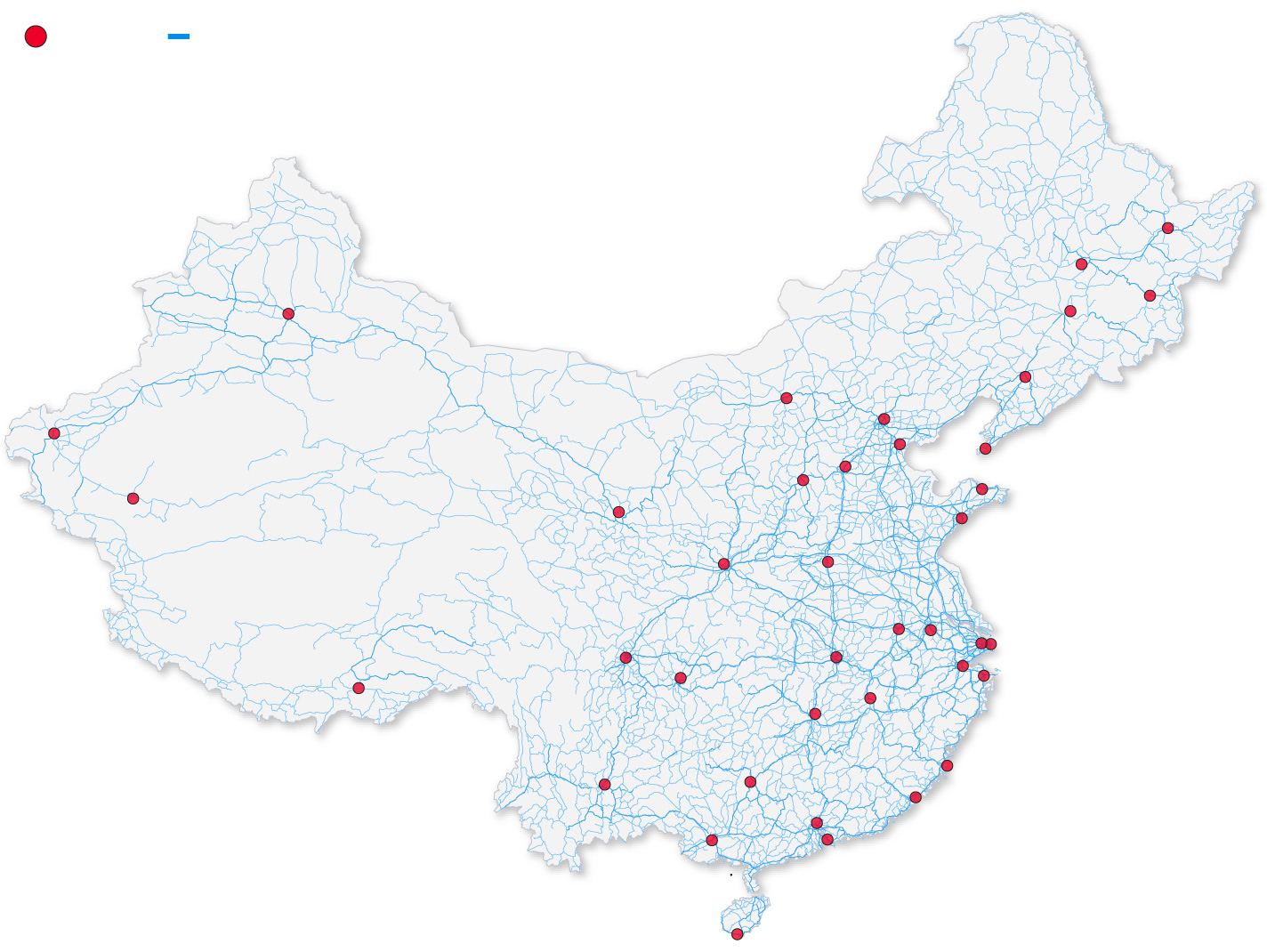

The first is that the infrastructure that has been built in the last thirty years or less is simply amazing, not just impressive but jaw-dropping. Most spectacular is the network of high-speed railway lines built since roughly 2005. Currently there are 30,000 miles of such lines, all built in the last twenty years. The total railway network, which has also been massively expanded, stands at 96,000 miles including the HSR lines with the plan being to extend it to 170,000 miles by 2050. According to the best estimates by outside observers, the return on this investment is between six and eight per cent. Since the system has largely been built from scratch, it features enormous brand-new stations the size of airport terminals. The trains, which run at 200 mph, are comfortable and clean and the ride is so smooth that the speed is almost unnoticeable.

China railways map

It is not only trains. There is also a series of airports all over China, most as big as major international ones in Europe. Again, these are brand new. Alongside the railways is a dense network of both long-distance motorways and modernised provincial and local roads. There are 114,000 miles of expressways with the rest of the national highway system amounting to 1.3 million miles (1.9 million kilometres). As with the rail system, this is being constantly extended. The big caveat is that building the infrastructure is one thing (not that Western countries are doing that) but the real challenge is maintaining it.

The other aspect of infrastructure that anyone visiting China notices is the urban development. China has seen a dramatic process of urban development in the last two decades, with new cities springing up everywhere and older ones adding millions of new housing units. This takes a distinctive form, which is high-rise and high-density. Chinese cities and towns have grown upwards as much as outwards. Cities feature forests of high-rise towers, typically of thirty to forty floors. The initial impression is of uniformity but on closer examination that changes. Most of the towers are not simple boxes but have decorative features as part of the design and what seems a single mass resolves into grouped clusters of towers with similar styles. At ground level it becomes clear that each cluster is fenced off and forms a single gated neighbourhood, with retail and other facilities on the lower floors of the towers. The new cities thus have a high-density modular structure.

China road network and airports

The other feature of Chinese urban development is how green the cities are. There are trees and green spaces everywhere with most of the trees clearly planted in the last thirty years. The expressways and major roads have ivy growing up the sides of supporting pillars and boxes of flowers and plants along their lengths, all maintained. The pattern is what is known as a “sponge city” with threads and “holes” of greenery and open space between the high-rise neighbourhoods and the older low-rise ones and the very high-rise commercial centres. This pattern is far less car-centric than its American equivalent and although there are many cars, they are not at present the primary means of transportation. That is the electric scooter with swarms of them zooming around all of the streets, supplemented by both public transport and walking.

Another difference between Chinese cities and many Western ones is their orderliness. There are no homeless people or beggars and although the cities are lively and dynamic you do not see or find anti-social behaviour. Public spaces are spotlessly clean, partly because of a veritable army of street cleaners (most of them older people) but also because littering simply does not happen. One reason for this is a low-key but pervasive police presence: each small neighbourhood has its own attached police officer with photographs of them displayed along with that officer’s mobile number for contacting them. Police are highly visible. However, the evidence suggests that the police are simply backing up strong social norms of public behaviour, which strongly disapprove of anti-social conduct.

The darker side of the orderliness is the degree of control. There are security checks at all transport terminals and most major historical sites or public buildings. Visiting many places requires photo identification, passports for foreigners, ID cards for locals. There is an important qualification to this though: while the security checks and ID system are uniform and national, the well-known social credit system is not – it varies considerably from one province or locality to another. This reflects a major feature of the Chinese state which is its relative decentralisation. The Party is not uniform and monolithic. Although there are national strategies and policies, each provincial or even city level Party has a great deal of autonomy and can pursue its own strategy to a great extent. As a result there is considerable variation in details of policy and strategy from one part of China to another. This is not novel – it reflects a system of governance found throughout the history of the Chinese state all the way back to its formation in 221 BC.

Women dressed in Qing Dynasty attire take souvenir photographs as they visit the Temple of Heaven during the weekend holiday, in Beijing Credit: Andy Wong/AP

This reflects one of the most surprising observations I made, the persistence and even reassertion of older Chinese ways of thinking and living. Although the cities and infrastructure are impressive, the striking feature is the prosperity and success of the countryside. Across most of China, rural towns and villages have new, modern housing, often funded by private savings. Alongside the network of major roads is a dense system of smaller paved roads and paths that connect the countryside to the national system. This is coupled with both near-complete electrification and internet provision. The pattern of agriculture is very traditional and strikingly different from the Western model. The rural landscape (and much of the open space around and within cities) is one of very small fields, more like allotments. What is practised is traditional Chinese intensive permaculture with regular rotation of crops and mixed farming, a pattern of agriculture that is very efficient in terms of yields but which does not rely on high energy inputs. It is however still very labour intensive but this is changing with urbanisation. However, there are still very strong connections between countryside and city, with many who have moved to the city retaining a connection with and responsibility contract for portions of rural land, which they still farm. The farming is very intensive – not a square inch of land suitable for farming is left idle no matter where it is.

Agriculture is only one of many ways in which old China persists and re-emerges. Traditional ideas, such as the polarity of Yin and Yang are as strong as ever. Among the young there is a clear revival of traditional religious belief and observance, notably of Buddhism, but also of Taoism and Confucianism. Buddhist temples are crowded with young people, particularly women, who come not as tourists but to pray. The Party is comfortable with this and in many regions actively encourages it, rebuilding Buddhist temples and even Confucian ones. (That is surprising because of Confucianism being the official philosophy of imperial China.)

In fact, the impression gained is that the ideological basis of the state is slowly but steadily shifting, to a hybrid one that owes as much to the historic traditions of Confucianism and Legalism as modern thought. The cult of Mao, while officially as strong as ever, is slowly fading not so much because of ideological repudiation as the simple passage of time. Mao is becoming simply another major historical figure, similar in many ways to his own role model, the First Emperor Ch’in Shi Huang Ti. The current system still has strong legitimacy but the Cultural Revolution is regretted. For middle aged people the figure who is admired is Deng Xiaoping, credited with the opening of China to the rest of the world and the transformation of the economic system from a command economy to a dirigiste market one. Another revered figure is Sun Yat Sen, the founder of the Republic in the 1920s. Uniquely, he is venerated on both sides of the Taiwan Strait and the actual policy of the state owes as much to his “Three Principles” as socialism (particularly “Nationalism” or Minzu and Welfarism or Minsheng).

There is a widespread popular interest in the historical past of China, and veneration of much of the history. One amusing aspect of this is younger people, particularly women, visiting historical sites while wearing historical period costume. This varies by region – in Beijing it is mainly Manchu court dress from the Qing dynasty, in Xi’An Tang era dress, while in the Yangtze Delta cities it is Song costumes. The past is not accepted uncritically but is generally admired and respected. Past figures who are widely admired are Ch’in Shi Huang Ti, the Hongwu and Yongle emperors from the Ming dynasty and Empress Wu and the Taizong emperor from the Tang. Generally, the Han, Tang, and Ming dynasties are admired, the Song and Qing less so. The common theme is that the figures and dynasties that are respected are ones seen as having promoted Chinese prosperity and power along with openness to the rest of the world, while the deprecated ones are those associated with Chinese weakness relative to the rest of the world and cultural decay. This all reflects another old idea that is reviving, that the crucial thing for state success is not so much institutions or policy but the quality of leadership.

This is a very dynamic and innovative society that is also intensely competitive at an individual and familial level. It is highly futuristic and forward looking but also connected to its past, which is venerated in various ways. It has an authoritarian but effective and competent government. How long all this will survive is another matter but right now China is an advert for the idea of “state capacity”. There is a strong cultural commitment to ideals of education and self-improvement, often very materialistic. One form this takes at a personal level is commitment to physical fitness and health, with public exercise classes being a major feature of urban life. This is coupled with a powerful work ethic.

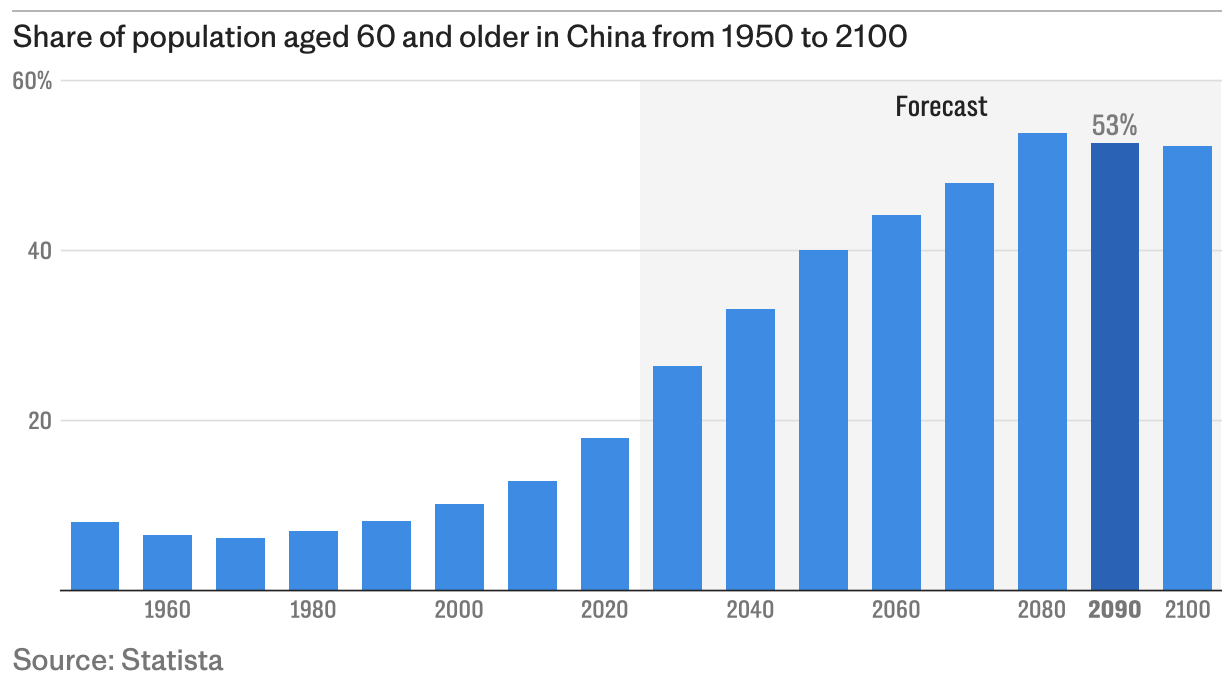

All of this faces challenges. It is not clear how long the ethical collectivism and work ethic will survive the impact of modern cellular communications and social media. There is concern, getting close to panic in official circles, about the below replacement birth-rate but, as elsewhere, there is no sign that the pro-natalist policies of the state are having any effect. The ageing population poses a massive challenge going forward but the current acute problem, as everywhere in the world, is housing costs in major cities – Shanghai has costs comparable to major metros in North America or Europe. That this coincides with massive and continuing supply suggests that it is not supply constraints that cause this but the financialisation of housing and the derangement of the global monetary system. One thing that many locals commented on was the continuing impact of the Covid pandemic – it has halved domestic air travel for example.

For now, China is, on all of the evidence, a dynamic society with a functioning and effective state and economy that is comfortable with its past and its identity. There is a strong commitment to engagement with and openness to the rest of the world and a desire to see China recover the kind of position it had under the Tang, as the leading world civilisation. We are only starting to see the impact this model will have on the rest of the world. For a long time, China saw itself as the central or middle kingdom of the world and the rest of the world regarded it as the most powerful and most civilised state – this only changed after the 1770s. We are almost certainly going to revert to that.