| |

Canada's China Gambit: Navigating a New Geopolitical Triangle

By Leon Hadar

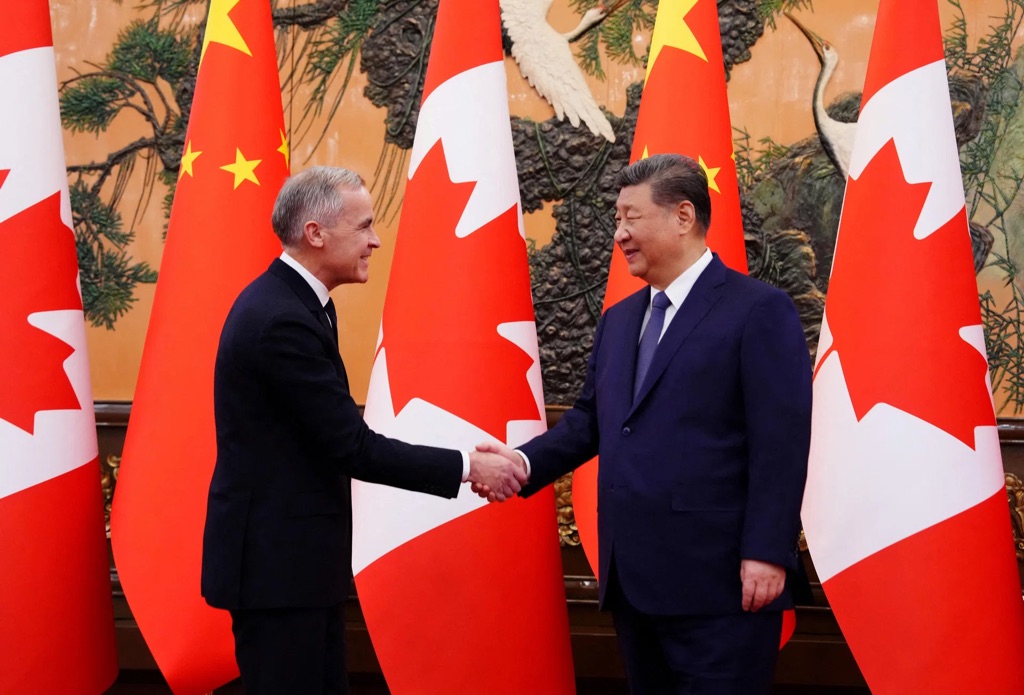

When Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney touched down in Beijing on January 16—the first visit by a Canadian leader to China in seven years—the geopolitical landscape had fundamentally shifted. The trade deal he secured, slashing tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles while winning market access for Canadian canola, lobster, and other exports, represents more than an economic transaction. It signals a potentially seismic realignment in North American trade policy and a test case for middle powers navigating an increasingly fractured global order.

The numbers tell part of the story: China will reduce tariffs on Canadian canola seed from 84% to roughly 15%, reopening a $4 billion market. Canada, in turn, will slash tariffs on Chinese EVs from 100% to 6.1% for up to 49,000 vehicles annually, rising to 70,000 within five years. But the implications extend far beyond agricultural exports and automotive imports. This deal forces us to confront difficult questions about economic sovereignty, strategic autonomy, and the future of North American integration in an age of great power competition.

Why Now?

Timing is everything in geopolitics. Canada's pivot toward China comes as Donald Trump returns to the White House with promises of aggressive tariff policies. The specter of U.S. protectionism—whether directed at allies or adversaries—has created a window of opportunity for Canada to diversify its trade relationships. With roughly 75% of Canadian exports flowing south of the border, Ottawa's economic vulnerability to American policy shifts is undeniable.

Yet the deal also reflects China's own strategic calculations. Facing continued tensions with Washington and seeking to fracture Western unity, Beijing has incentives to demonstrate that engagement remains possible and profitable. The elimination of retaliatory tariffs imposed in 2025—measures that devastated Canadian canola farmers and seafood exporters—offers Beijing a relatively low-cost way to drive a wedge between the United States and its northern neighbor.

From Canada's perspective, the deal addresses real economic pain. Canola exports to China plummeted by over two million tonnes following the tariff war. Prairie farmers faced collapsing prices. Atlantic fishers lost a critical market. The promise of unlocking nearly $3 billion in export orders offered immediate relief to politically important constituencies.

Integration vs. Independence

The most contentious geopolitical dimension of the Canada-China deal involves its potential conflict with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement. While the USMCA doesn't explicitly prohibit trade deals with non-parties, the introduction of Chinese EVs—even at limited volumes—into the North American market raises thorny questions about rules of origin, national security considerations, and the coherence of a shared continental trade policy.

Critics, including Ontario Premier Doug Ford and labor leaders, argue that Canada is sacrificing North American manufacturing competitiveness on the altar of short-term agricultural gains. The automotive sector, they contend, employs far more Canadians than canola farming, and opening the door to subsidized Chinese vehicles threatens the integrated supply chains that underpin thousands of jobs across Ontario, Michigan, and beyond.

Defenders of the deal counter that Canadian sovereignty includes the right to pursue its own economic interests, particularly when those interests have been casualties of broader trade conflicts not of Canada's making. They point out that the United States itself maintained significant trade with China even during periods of heightened tension. Why, they ask, should Canada be more Catholic than the Pope?

The answer may lie in asymmetry. Canada's economy is far more dependent on trade with the United States than vice versa. Washington has historically shown limited tolerance for independent Canadian action on matters it deems critical to American interests—and competition with China sits at the top of that list. The risk is that Canada's tactical gains in Beijing translate into strategic costs in Washington.

The Middle Power Dilemma

Canada has long prided itself on its middle power diplomacy—the ability to bridge divides, build coalitions, and champion multilateral solutions. But the emerging bipolar competition between the United States and China severely constrains this traditional role. As great powers demand loyalty and punish fence-sitting, the space for independent middle power action narrows.

The Canada-China deal can be read as either an assertion of middle power agency or evidence of its obsolescence. On one hand, it demonstrates that Canada retains the capacity to pursue economic diplomacy on its own terms, refusing to be reduced to a mere appendage of American strategic planning. The deal's emphasis on pragmatic, sector-specific cooperation—energy, agriculture, trade—rather than broad ideological alignment reflects classic middle power statecraft.

On the other hand, the fierce domestic backlash and concerns about American retaliation suggest that Canada's room for maneuver may be more illusory than real. If middle powers can only act independently on issues the great powers don't care deeply about, then their autonomy exists solely at the margins.

Scenarios and Implications

Three broad scenarios seem plausible. In the optimistic view, Canada successfully diversifies its trade relationships without sacrificing its primary partnership with the United States. Chinese investment flows into Canadian manufacturing, creating jobs and technology transfer. The limited EV quota proves manageable, and American concerns are assuaged through transparent implementation and continued Canadian commitment to North American defense and security cooperation.

A more pessimistic scenario sees the deal triggering American retaliation—whether through formal tariffs, informal pressure on cross-border supply chains, or exclusion from sensitive technology-sharing arrangements. Canadian automotive workers bear the brunt as investment flows elsewhere. The agricultural gains prove temporary as China uses renewed market access as leverage for political concessions. Canada finds itself worse off on all fronts: alienated from its primary ally while gaining little lasting benefit from its relationship with Beijing.

The most likely outcome probably lies between these extremes. Canada will extract some economic benefit from renewed access to the Chinese market while accepting that its relationship with Beijing will remain transactional and carefully bounded. Relations with Washington will experience friction but not rupture, as both sides recognize their mutual dependence. The deal will stand as a data point in an ongoing negotiation over how deeply integrated North America should be in an age of geopolitical competition.

Hedging in an Uncertain World

The Canada-China trade deal defies simple characterization. It is simultaneously pragmatic and provocative, economically rational and geopolitically risky. For a middle power caught between great power competition, it represents an attempt to preserve some measure of strategic autonomy—to hedge against American unpredictability while not fully committing to either side of the emerging global divide.

Whether this hedging strategy proves sustainable depends on factors largely beyond Canadian control: the trajectory of U.S.-China relations, the willingness of both great powers to tolerate third parties pursuing independent paths, and the resilience of the rules-based trading system that has underpinned Canadian prosperity for decades.

What seems clear is that the old certainties—that Canada could prosper through privileged access to the American market while maintaining arm's-length commercial relationships with other major economies—no longer hold. The world has entered a more zero-sum phase, where every economic engagement carries geopolitical weight and every partnership must be measured against its impact on primary alliances.

Canada's China deal may not reshape the global order. But it offers an early test of whether middle powers can chart their own course in an increasingly polarized world—or whether the gravitational pull of great power competition will prove irresistible. The answer will matter not just for Canada, but for all nations seeking to preserve some autonomy in the emerging geopolitical landscape.